Shortly after the referendum in 2016, I was invited to give a talk at an event held by the hospitality industry in London. It was, as you might imagine, well organised and would have been a fairly cheerful occasion had it not been for the UK’s decision to leave the EU.

Hospitality was, and is, dependent on large numbers of foreign workers and not just to serve food and drinks. Erecting fields of marquees, installing and running the bars and kitchens, lights, toilets, sound systems and audio-visual kit, takes some pretty skilled people.

This is a huge industry, that needs lots of people, often at short notice. Young, hardworking Eastern Europeans willing and able to turn up at a few hours’ notice had long been its bedrock.

Hardly surprising, then, that it was hard to find anyone at this event who voted Leave. But when I asked the question, one woman put her hand up. She ran an event catering company, so I asked her why she had voted for Brexit.

“Well,” she said, “I would rather the work went to British people, they will need training but there is no reason why they can’t do the work”. I asked her how much she was planning to spend training British people. “Nothing, that’s the government’s job,” she said.

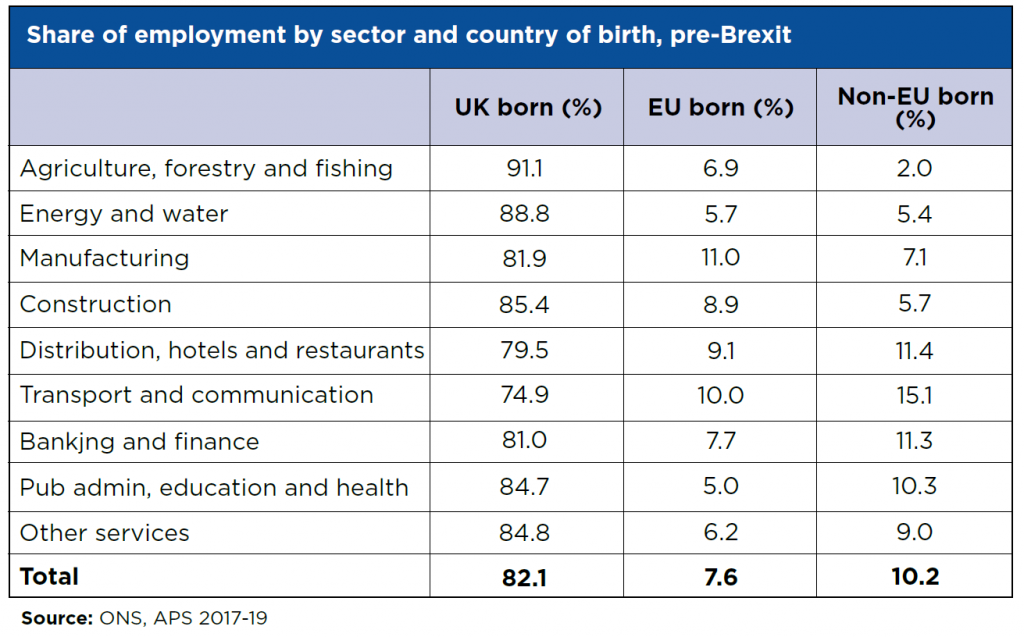

Five years on and she is probably still waiting, because the government has done virtually nothing to prepare the workforce for Brexit. The British economy, let alone the hospitality industry, is dependent on foreign workers and about half of them are from the EU. Fully 7% of the British workforce is from the rest of Europe; in some industries it is a far higher proportion than that.

Ever since Theresa May imposed her red lines, it has been obvious that ending freedom of movement would mean fewer EU workers. But what has the government done to fill that gap? Virtually nothing, and on top of that the existing training system is falling to pieces.

Apprenticeships would be the obvious way to at least ameliorate the situation. Go to any careers fair and you’ll see bright kids queuing up to work and train and get paid at the same time. The fear of student debt has made it even more attractive and these days you can do an apprenticeship in almost anything, from accountancy to zookeeping.

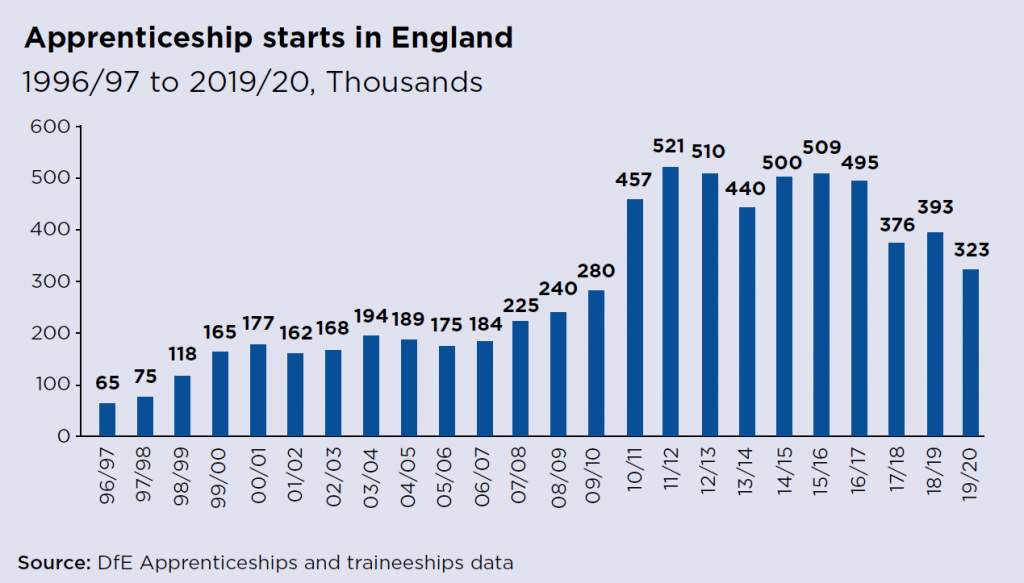

But the apprenticeship system is failing. Seven years ago the government introduced the apprenticeship levy, a 0.5% tax on the payroll of companies that paid more than £3 million in wages a year. The idea was that they could claim the money back to run their apprentice schemes, while smaller companies would have most of their costs paid for by the government.

It has been a disaster. Instead of increasing the numbers of new apprentices, they fell and have kept falling. Smaller companies found the system complicated and difficult to work, larger firms saw it as a hidden tax and just wrote off the money.

In 2019, the levy brought in £2.8 billion and paid out £864 million. Many larger firms spent the money on ‘training’ established managers instead of young workers at the start of their careers, the result is that there have been hundreds of thousands of fewer apprentices than before the levy was launched.

What has the government done to fix the system? Very little, six years on and the system is now doing even worse, with Covid destroying even more apprenticeships, despite the chancellor offering to pay companies much more to take them on.

It was patently obvious from the get-go that this ‘reform’ was destroying training not increasing or improving it but all the government did was mutter about teething problems.

Industry after industry has begged the government to change course, reform and improve the system, abandon the levy as a complete failure and start again.

But it has either refused or been so busy doing other stuff that such requests have gone to the back of the queue.

Whatever the reason it has been a disaster, which Covid has only made worse. As the president of the CBI, Lord Bilimoria, told the Recruitment and Employment Confederation’s annual conference in June “we have a perfect storm”.

Some 1.3 million immigrants left the UK because of Covid and no one knows how many will come back and there is now a points-based system for new immigrants from the EU which makes employing staff to replace them far more difficult.

The system is tedious, complicated, costly and inefficient. A committee decides what skills the UK is short of and sets a high pay barrier to try to keep out the rest. Laissez-faire Thatcherism it isn’t.

That is why the road haulage industry is begging for dispensations for lorry drivers to make up for an appalling shortage that is threatening to leave supermarket shelves empty.

So are farmers with crops rotting in the field, construction firms, food factories, bars and restaurants and many other sectors. All such appeals are likely to fall on deaf ears or get temporary exemptions which can be closed later.

All of this was foreseeable, ministers were warned time and again by numerous industries which begged for help, but they were dismissed as Remoaners, who just had to face reality and embrace Brexit.

An opportunity did exist over the last 5-6 years to do something to help; to boost further education, train new British lorry drivers, bricklayers, plumbers and hospitality staff but it has been wasted, criminally wasted.

The Brexit-supporting press has now taken to blaming Brussels for the ‘red tape’ that stops these jobs being filled by our European neighbours. This is the exact opposite of the truth; all the new barriers and red tape are completely homegrown.

The same papers’ letter pages are full of calls for the “feckless unemployed” and the young to be shipped to the fields to pick fruit, almost as a form of national service.

If the day after the referendum result, the government had sat down and thought seriously about what needed doing this would never have happened. It would then have poured time and effort into improving the apprenticeship scheme, thrown money at further education and identified which industries were most dependent on foreign workers and allowed them to recruit abroad, but it didn’t.

We are now living with the consequences of the ultras’ insistence that Brexit had to be as hard and ‘pure’ as possible. Since in their ideological bubble that can only be a “good thing”, the consequences are not their concern.

But a responsible government could have seen this coming or listened to those who knew what was happening and then spent years preparing. Any responsible government.

Jonty Bloom is a freelance journalist and former BBC business correspondent. Follow him @jontybloombiz

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37