We are teetering on the brink of a generational war.

Wherever you look, battles and betrayals across the generations are poisoning relations between old and young. Emerging generations of ‘social justice warriors’ find themselves facing a ‘war on woke’.

Baby Boomers are selfish sociopaths who’ve destroyed the planet while callously ignoring desperate appeals from the young – and now they may be the first to benefit from changes to social care, financed by a proposed National Insurance hike that will disproportionately affect younger and working-age people.

This, at least, is the endlessly repeated story. But my book, Generations, suggests very little of it is true.

More importantly, these myths and phony battles distract us from the real challenges we face. We are losing faith in a better future for our kids, as inequality is increasingly handed down across generations.

One of the most destructive stereotypes is the assertion that older generations don’t care about the environment. It has crept into so many discussions about climate concern that it’s become an accepted truth.

For example, when Time magazine named Greta Thunberg their person of the year in 2019, they called her a “standard-bearer in generational battle”.

The US singer Billie Eilish was more direct: “Hopefully the adults and the old people start listening to us [about climate change]. Old people are gonna die and don’t really care if we die, but we don’t wanna die yet”.

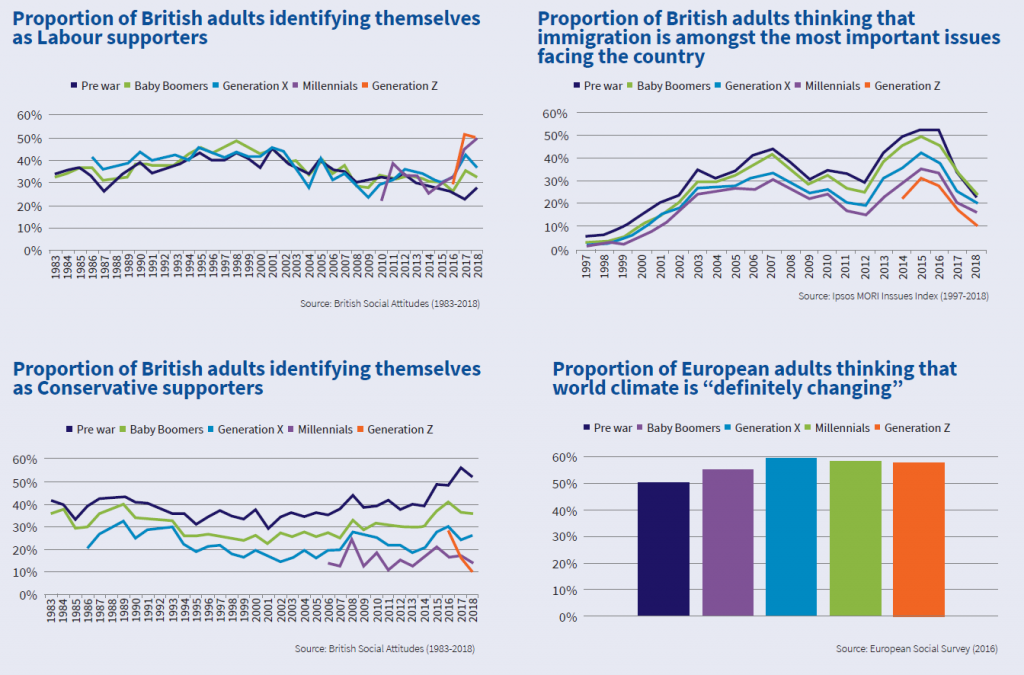

But that’s not held up by the evidence. For example, a major Europe-wide survey has shown that there is no real age divide in the recognition of climate change. Around half of the Pre-War generation think the world’s climate is definitely changing. That figure rises to around six in ten among Gen X (now in their 40s and 50s), the generation most likely to hold this view, with younger generations slightly less likely to be certain.

In contrast to much of the rhetoric, then, we are a long way from either universal acceptance of human-made climate change among the young, or universal denial among older generations.

And the clichés are even further from the truth when we look at how the different generations act. Claims abound that Millennials and Gen Z are ‘purpose-driven’ consumers, only supporting sustainable or socially responsible brands.

But it’s actually Baby Boomers who are most likely to have boycotted a company in the last 12 months in the UK, with Gen Z about half as likely. On this measure at least, ‘cancel culture’ is more of a middle-aged thing.

The unthinking ageism that has crept into much of the discussion about climate change is a serious problem. It completely misreads the strength of connection up and down generations, where parents and grandparents care deeply about the legacy they’re leaving for their children and grandchildren – not just their house or jewellery, but the state of the planet.

Most importantly, it ignores the growing demographic weight and financial power of the older population. Our societies are ageing, and older people are getting richer: in the UK, over-fifties account for around one-third of the population but 47 per cent of consumer spending, which has increased by eight percentage points since 2003.

It’s a similar story of exaggerated difference on cultural attitudes. I’ve examined opinion data on a wide range of issues, including race, gender and sexuality, over the last four or five decades, and the very clear picture is of constant and remarkable change over that period – not a sudden shift with the latest generation of young.

For example, it is hard to believe that, as recently as 1987, 48 per cent of the British population believed that ‘the job of the man is to earn money, the job of the woman is to look after the home and family’.

Now only 8 per cent of people say they hold this view, most of them in the oldest generation, born before the end of the Second World War.

The crucial point is that each new generation of young is always at the leading edge of culture change. The issues vary, but there is nothing in the data to suggest that the gaps between today’s young and other generations are particularly unusual.

For example, support for the Black Lives Matter protests is roughly twice as high among the youngest compared with the oldest age groups, and the young are roughly twice as likely to be ‘ashamed’ of our imperial past than older groups. But these gaps are no different in scale from those seen in the past between the Pre-War generation and Baby Boomers on race or homosexuality.

It feels different now. But that’s because the broader context has changed. We have more fractious politics, and a media and social media that are incentivised to highlight extreme views and arguments. The explosion in coverage of “culture wars” in the UK in recent years is more a cause of generational division than a consequence of it.

This rhetoric does have real consequences. When you put cultural division at the heart of politics, you’re bound to create an age divide in party support. And that’s what we’ve seen in recent years. For example, support for the Labour party has traditionally had no real relationship with age – support cut across generations. But this changed hugely at the 2017 general election, and the pattern was repeated in 2019, with the youngest now around twice as likely to support Labour as the oldest generation.

But the real destructive power of generational myths is that they are a distraction from some truly shocking trends.

First, all generations are losing faith in a better future for young people. In 2003, most people in Britain expected young people to have a better future than their parents – but in a new survey conducted for the book, only a quarter of Brits do.

This is a real problem, as we know this is important to people: 77 per cent of people agree that every generation should have a better standard of living than the one that came before it, with only 15 per cent disagreeing. The end of generation-on-generation progress isn’t just a concern for young people: given our strength of connections up and down the generations, through our families, we all feel it.

More than this, whether the future will be better for your kids is increasingly dependent on the resources you have. For example, the likelihood of obesity in children was once unrelated to their social class, but this has become a key factor for recent generations.

More generally, the extraordinary growth of wealth and its concentration in a section of older age groups is one of the key economic stories of our time. Future inequalities between generations are being ‘baked in’, as advantage and disadvantage are increasingly handed down in an incipient caste system.

It used to be that ‘today’ would always be the right answer if you were asked when you would like to have been born. This was testament to the incredible progress we have seen and how this moved everyone up, even if the better-off were progressing more quickly.

But we are now seeing actual reversals for those with fewer resources in richer countries, which the COVID pandemic has only accentuated.

But even prior to the pandemic, we had seen falls in life expectancy among women in the most deprived areas in England, and for both sexes in deprived areas of some regions, such as the north-east of the country. These groups are currently exceptions, but increasing proportions of the population will get pulled in as the concentration of advantage continues.

These are the real generational stories of our time, not nonsense about avocados and cancel culture.

HOW THE GENERATIONS DIVIDE

PRE-WARRIORS Known in the US as the ‘Greatest Generation’, this age group takes in everyone born before 1946. More likely than the other groups to be economically and socially conservative, the youngest Pre-Warriors would have been 70 or 71 in the fateful year of 2016, when UK pensioners were more than twice as likely as under-25s to have voted Leave and US citizens over 65 went for Donald Trump over Hillary Clinton by 53%-45%.

BABY BOOMERS Born between 1946 and 1964, with a nickname that entered common currency towards the end of that period in recognition of the post-war uplift in childbirths. Boomers commonly value family time and are goal-centric. They’re also on Facebook (90% have an account) but may be wary of other social networks, where they can be dismissed by younger groups with a sarcastic “OK Boomer”.

GEN X A name originally used for Boomers – in 1964, the Observer wrote: “Like most generations, ‘Generation X’- as the editors tag today’s under 25s – show a notable lack of faith in the Old Ones.” It came to define the group born between 1965 and 1979 after the publication of Douglas Coupland’s Generation X: Tales for an Accelerated Culture (1991). More digitally savvy than the generation before them, spending 7 hours a week on Facebook.

MILLENIALS Born between 1981 to 1994, Millennials – also known as Gen Y and Baby Busters – typically have multiple social media accounts and may have paid the price in social connections. 30% of millennials say they often feel lonely compared to 1 in 5 members of Generation X. They have less brand loyalty than previous generations and have little patience for poor quality or service.

GEN Z The Z-ers – the nickname was coined by Advertising Age magazine and seems to have beaten out other suggestions like Zoomers and iGeneration – were born between 1997-2021 and will have received their first mobile just over the age of 10. They now spend an average of 3 hours a day on a mobile device. One in 4 say they are more likely to pay a premium price for a product if it is eco-friendly.

GEN ALPHA Born in 2012 and after, Alphas have typically been raised with technology embedded into their everyday lives. Their nickname comes from a 2008 survey in which rejected contenders included Generation Surf, the Technos and the Onliners. Shaped by the social justice movements, 95% put the environment as their top priority, compared to 57% of Millennials and 37% of Boomers

- Bobby Duffy is Professor of Public Policy, Director of the Policy Institute and author of Generations: Does When You’re Born Shape Who You Are?

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37