It is hard, as we enter October and the final months of the year, to believe we could be facing a harder winter than the last one.

Last year we endured extreme Covid restrictions, an avoidable second wave of deaths and the bitter sting of ministers cancelling a much-promised Christmas at the very last moment. And yet here we are.

We can hope – and are all fervently hoping – we will not see another horrifying spike of coronavirus hospitalisations and deaths. But they have hardly gone away: close to 1,000 people are being admitted to hospital with Covid each day, putting an exhausted NHS heading into winter onto its knees.

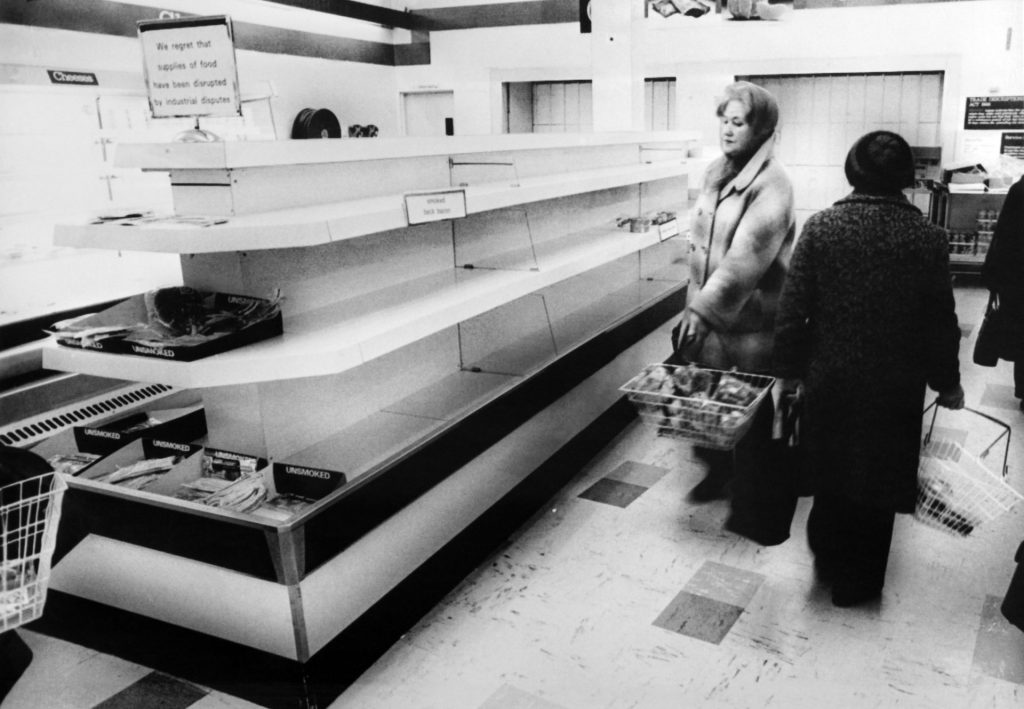

But that’s only one of our problems. The government is already talking about deploying solders to deliver fuel, after queues and violence at petrol pumps across the country, bins are going unemptied for weeks at a time, empty shelves are a fact of life in our supermarkets and a looming energy crisis has raised the prospect of blackouts.

The UK’s laundry list of woes is inevitably already drawing comparisons to the ‘winter of discontent’ of 1978-79. The memorable phrase – borrowed from Shakespeare by the Sun to sum up those chaotic months – brings to modern minds scenes of streets strewn with rubbish, shelves left empty amid widespread strikes, with even the dead left unburied, all among vile weather, too.

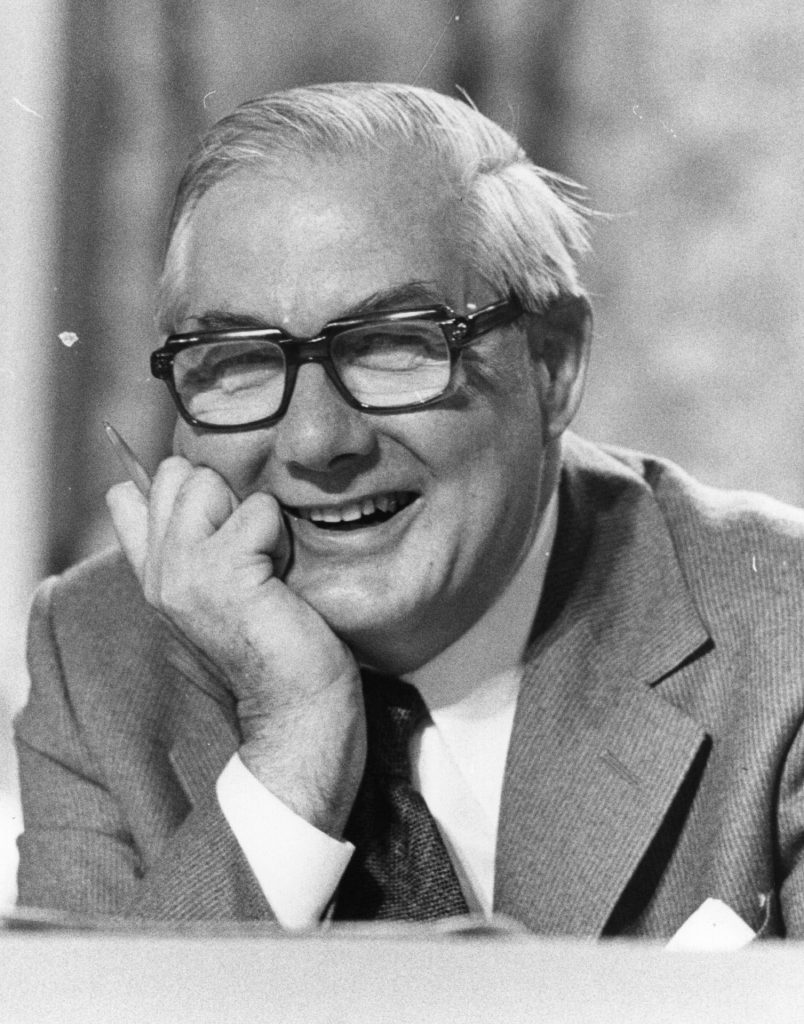

That traumatic winter arguably threw the governing Labour Party out of power for almost 20 years. Such was the popular memory of that dismal time that voters were unwilling to forget or forgive what they saw as the bungling that had led to the crisis and the lack of leadership to resolve it.

After all, though seemingly sudden, the events of 1978-1979 – like those of this winter – had been years in the making. They were fuelled in large part by a government facing the need to battle inflation versus workers determined to secure increases in pay.

The government was attempting to cap pay rises for public workers at 5%, in a bid to cut inflation – which had peaked at almost 27% a few years before. The problems came when Ford resolved a strike at its plant with a pay hike of 17%, prompting public sector unions to demand higher wages and then launch strikes as these were refused – all against the backdrop of the coldest winter the UK had faced in well over a decade.

While pay levels in certain sectors are a factor in the current mess Britain is in, it is not in the causes that people are finding parallels between the two winters. Instead, what they share is a sense of sprawling crises on multiple fronts and a perception of events slipping beyond the control of the government.

Then like now, events – the inescapable impacts of which are being felt by every section of society – have suddenly exposed chronic, underlying problems in the UK operates and incompetence at the top about how to resolve them.

Ministers, of course, would disagree. So let’s start with some reasonable arguments they might make. Foremost among those is that there has been a global pandemic, and it has caused an awful mess. A shortage of lorry drivers is a major factor in our problems, and this really is happening internationally.

Covid has disrupted supply chains in dozens of ways big and small, and modern supply changes are like an intricate Swiss watch: amazing in their precision and brilliance when they’re working, but time-consuming to repair when smashed. Getting everything working as it should will take months more (at least).

It’s also fair to say that panic has been a big factor in the shortages we have seen to date. The UK is facing a real energy crisis (albeit a smaller one than that behind the three-day week of the 1970s) – but it is primarily about the loss of a crucial electricity interconnector with France, which supplied the UK with power when needed.

Proving, at last, that the UK is no longer a nation of shopkeepers but rather a nation of motorists, people heard the words ‘energy crisis’, let their minds leap immediately to ‘petrol’ and leapt to the pumps, spurred on further by a few stations who had late deliveries of fuel thanks to the driver shortage.

That’s fine up to a point – but preventing panic is one of the government’s jobs. That’s what they’re there for. And it’s safe to say they’ve shown an absolutely woeful performance at that task.

Ministers have spent months denying the very possibility of problems, gaslighting the public as to the problems’ causes, and contradicted and even attacked key industry leaders even as they tried to sound the alarm. That leaves much of the country fairly suspicious of the government even before shortages begin.

Whether on trust or simply on understanding how to fix complex problems, this government is falling short: leaving aside entirely the question of intent or malice, crises are exacerbated by government incompetence, and competence is a hard thing to find in the current cabinet.

There are clear lines to be drawn between the Brexit this government pursued and delivered, and the crises we are seeing this winter. By not acknowledging that link ministers are simply deepening the difficulties the country is in. Its state of denial over Brexit means that it cannot even be trusted to get to grips with those elements of our current winter of discontent that are less intrinsically tied to it, such as the government’s incoherent energy strategy.

In the flattest of terms, a comparison of 2021’s winter to 1978’s should show the former isn’t as bad in absolute terms – but those terms would be ridiculous. The world in general and the UK in particular is a much richer place than it was then.

On top of that we have had more than four decades of rapid technical progress, allowing us to build complex and brilliant international supply chains – retailers can respond to shortages before they even happen, and have mitigated them by curbing product ranges, focusing on key lines, and thousands of other small changes. Every day the modern world papers over the cracks as best as it can.

More than that, 1970s Britain knew it was a second-rate country. It had become used to being a second-rate country, whose best days were behind it – as a result of the horrors of war and the poverty of rebuilding, many of its people had lived through far worse. Yet people were still furious at the crises.

A huge component of why this winter is set to be grim is because the government deliberately and without understanding – or listening to warnings of – the consequences of its actions, chose to sever much of what improved the country since 1979.

Success in the modern world relies on easy, frictionless international trade. The government in its blind arrogance thought it could get the benefits of that without the compromises it entailed, and even when Brexit negotiations showed this wouldn’t be possible, decided to plough on regardless and see what happened.

This winter we will all see what has happened. And there’s little reason to believe that what comes after that will be better. After all, the three-day week that is often lumped in with memories of the last winter of discontent was actually introduced far earlier in the 1970s in response to an energy crisis. And that crisis didn’t just go away; the issues behind it brewed up again as the winter of discontent a few years later.

We are governed by the denial-stricken architects of the crisis we’re living through, and they will not be converted by a mere bad few months. Instead, they’re seeking three-month sticking plasters – Scrooge visas, asking truckers and poultry workers to come to the UK only to be kicked out on Christmas Eve – for the new structural problems they have created.

To look at long-term fixes would be to deny their only real political accomplishment, of getting Brexit ‘done’. So our future looks to be one of staggering from crisis to crisis, patching up each new disaster as we await the next – until someone finally convinces the public it’s had enough of all of this and it’s time to try something new.

It’s hard to look at the UK political scene and think this feels imminent. In 1979, Britain did have an opportunity to try something different – for good or ill – and chose to do so with the election of Margaret Thatcher.

Such a change of fortunes is not on the cards this time. It’s more than four decades since the last winter of discontent. The next one may be around the corner.

The long winter

July 1978

Government wants to set the cap on wage rises to a limit of 5% a year. Unions reject continued limits and demand return to collective bargaining

Oct 1978

Labour’s Militant group passes motion for the government to stop intervening in wage talks. Callaghan accepts, but vows to fight inflation

Nov 1978

Ford workers strike settled with 17% pay increase, prompting government threat of sanctions. Temperatures plummet ahead of freezing winter. Towns cut off, trains stuck as councils struggle to clear snow, blaming staff shortages

Dec 1978

Callaghan narrowly wins confidence vote. Backs down on pay sanctions. Lorry drivers demand 40% pay rise. Tanker drivers go on strike. Petrol supplies limited. Some struggle to heat homes. Rugby and football matches cancelled

Jan 1979

Hauliers go on strike after refusing 13% pay rise. Petrol distribution held up and stations closed. Strikers picket main ports. On return from Caribbean summit Callaghan plays down seriousness of situation. Next day’s Sun publishes the headline “Crisis? What crisis?” and phrase from Shakespeare’s Richard III, “Now is the winter of our discontent…” Public sector unions call a big strike following several big private sector rises. Train drivers begin series of strikes. Nurses call for 25% rise. Ambulance drivers go on strike, some refusing to attend 999 calls. Grave diggers and crematoria workers strike in Tameside and Liverpool. Corpses stored in Liverpool factory. Piles of rubbish attract rats as binmen strike. Leicester Square dubbed ‘Fester Square’

March 1979

Callaghan government loses confidence motion by one vote. General election called

February 1979

Gravediggers settle for a 14% rise after two weeks. TUC General Council agrees an end to the action. Strikes start to wind down

May 1979

Conservative government of Margaret Thatcher elected, promising to curb union power

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37