The internet has long been a political battleground, but one corner of the web is home to a particularly dirty kind of warfare.

Social media is the new battleground for politics the world over. Ever since Barack Obama’s 2008 presidential victory was dubbed the first ‘Facebook election’, likes and shares have been the currency of political campaigns. That’s why all the significant Leave and Remain campaigns spent the lion’s share of their budgets online in last year’s referendum battle, and the various parties are preparing to do the same for this year’s general election. But there is more to the art of online persuasion than meets the eye.

Everyone who is active online today will be aware that politics in the social media age is less about winning arguments and more about stirring up feelings. Mostly of outrage and fear. We’re in a new era of identity politics that lends itself like never before to ‘snackable’ bites of information – and disinformation – designed to stoke anger and hate.

Enter the political meme and its best friend, the hashtag. If you’re baffled by the terminology of the online world think of these phenomena as new versions of the political advertising poster and its snappy slogan.

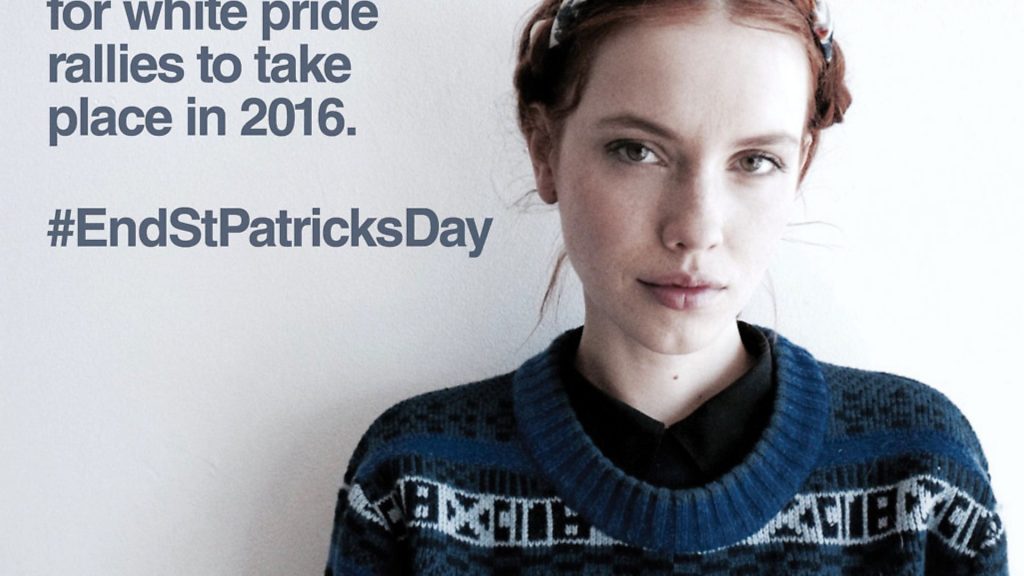

The term ‘meme’ takes its name from the biological ‘gene’. It was originally coined to describe a piece of information that is passed on socially – as are genes, in biological reproduction. The hashtag is simply a way to help sort information so that it can be easily tracked, found and shared. Put them together and sometimes they go viral. Like the one shown on this page

For most people this meme appeared apparently spontaneously on Twitter, in the run up to St Patrick’s Day. If you search for #EndStPatricksDay there you’ll see it was shared and commented on thousands of times. There is even an account dedicated to promoting it.

So what was the thinking? Who created it and why? To understand that you only have to look at the predictable reactions.

It was designed to mock SJWs (aka Social Justice Warriors aka ‘liberals’ aka non-racist people). And it was created by someone on a website you might have never heard of, called 4chan.

And it was created by someone on a website you might have never heard of, called 4chan.

To delve into 4chan is to glance at the modern day equivalent of a Hieronymus Bosch painting. It’s a ‘free speech’ message board that’s been around for 13 years, popular because it is 100% anonymous. That makes it the perfect place to talk about anything. And 4chan users do talk about anything.

A visit to 4chan is like stepping into a party where everyone is masked and the main topics of conversation are Holocaust denial, white supremacy, the secret plans of Israel to take over the world and how George Soros already controls everything in the New World Order anyway. And stuff we won’t even mention in a family publication.

In my first five minutes on 4chan I saw some pictures I cannot now un-see (one of which literally did give me a nightmare a couple of nights later) so be warned, if you’re curious enough to visit for yourself. It is as uncensored a place as you’ll find this side of the Dark Web.

But I also saw some very familiar connections with far right extremist material many of us have become familiar with on more conventional social media platforms.

It’s clear that 4chan is a breeding ground for (mostly) fictitious material designed to whip up hate – in no particular order – against liberal people, people of colour, Jews, women, Muslims and feminists.

Many of these memes linked through to Twitter in particular and appear on accounts where they are being shared to a wider, more conventional audience.

There are no surprises that one of the dominant themes on the political discussion board (known in 4chan speak as /pol) has been how to promote Marine Le Pen in the French elections. Many users have been busy discussing how to create memes that will discredit the centrist candidate Emmanuel Macron too. Most of the discussions fizzle out, with no output, but some result in vulgar – if crude – photoshop treatments and false rumours, ready for releasing into the world of Facebook and Twitter.

To better understand the dynamics of this strange place – and its impact on the real world – an increasing number of academics are closely monitoring sites like 4chan.

One of them is Jeremy Blackburn, a Computer Science PHD and expert in the analysis of online behaviour. About to take up an assistant professorship at the University of Alabama, Blackburn describes his research background as ‘online behaviour, including cheating and toxic behaviour in the online gaming community’ and is now turning his focus onto ‘ad hoc semi-organised non-hierarchical campaigns promoting hate speech and online harassment’.

He explains: ‘There has always been a darker side to the internet but what has changed is the scale of this behaviour. It has stopped being a secret club, like you used to see in the old news groups of the early internet, and is now big enough to have an impact in the real world.’

Blackburn has been analysing the #pizzagate meme, in which Hillary Clinton is supposedly connected to a fictional organised child abuse ring and which resulted last year in a real life shooting in a restaurant. He says that although #EndStPatricksDay passed him by, it bears all the hallmarks of a 4chan ‘prank’.

He says: ‘They tend to take two approaches. One is to openly promote something straight up, like #Trump4President, and the other is to trick people into getting outraged by something they made up.

‘It goes back to the history of 4chan and how it started as a place for having fun and trolling people. Although users were saying and doing objectionable things, it was funny. But in the last five years a hard right wing slant has come in and that has attracted a lot of people who actually believe this stuff.

‘So although one of the goals has always been to laugh at people and get amusement from affecting the world in some way, political motives and genuine fringe ideologies now dominate the board.’

It doesn’t always work, however. Blackburn describes a failed attempt to disrupt Google’s ‘Project Jigsaw’ which uses machine learning to identify and avoid promoting sites focused on hate speech in search rankings.

He explains: ‘A group of 4chan users came up with a thing called Operation Google. The goal was to confuse Google’s machine learning algorithms so that Google would actually end up banning itself from search results.

‘The plan was to substitute all racial slur phrases with the names of tech companies so that the ‘n’ word was replaced with ‘google’, a disparaging word for ‘Jew’ was replaced with ‘skype’ and so on. We watched them attempting to organise this but we saw no impact at all outside 4chan and ‘Operation Google’ died after a few days.

‘But 4chan is the perfect avenue to test and push any agenda you want because there are no consequences. The reason they have been pushing the Le Pen stuff is because after the US election and a few other less important elections in Europe, promoting her is seen by them as the next best shot at having an impact in the real world. They pushed Brexit last year, of course, but Le Pen has been the next big push.’

This mix of prankster behaviour, extremist ideology and consequence-free anonymity makes the 4chan community potentially significant players in liberal democracies everywhere, even though they are off the radar of most people. Certainly the chances are that most people reading this will have brushed up against 4chan without ever knowing it.

But there are some signs of opposition creeping in on the site itself. During my research I was struck by the amount of counter-harassment I saw from a more ‘liberal’ perspective. Blackburn says that the election of Donald Trump saw a surge of resistance on 4chan that has made things ‘more interesting’. I may have even dipped my own toe in the water – strictly for professional purposes. And to make 4chan a bit more interesting.

Mike Hind (@MikeH_PR) is an independent journalist, PR and marketing consultant

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37