JAMES OLIVER tells the story of African cinema’s past and its promising future.

Light is an under-appreciated part of cinema. It’s light – the brighter the better – which makes the medium possible in the first place, trapping the images in the camera and then freeing them again in the projection beam. It was the light that drew filmmakers to that corner of southern California that became Hollywood.

Trouble is, light alone is not enough. If it was then African cinema would lead the world, for what mutton-chopped Victorians liked to call ‘the Dark Continent’ is illuminated by the most brilliant sunshine.

But… the infrastructure to capitalise on this blazing light barely functions, and investment is hard to find. Africa’s film heritage is not extensive, especially from the sub-Saharan part; exclude movies made in North Africa (as we shall do throughout to keep things focused) and you’re left with a scanty number of movies.

Then take out films directed by well-meaning whites (and yes, we’re doing that too) and the archive is depleted yet further.

All that is as westerners would expect. Our view of post-colonial Africa has traditionally been bleak; in 2001, Tony Blair called it ‘a scar on the conscience of the world’ and our news coverage emphasises catastrophe, be it natural or man-made.

But maybe we should re-write the script because there are better stories to tell. The past 20 years have seen a steady growth in Africa, and while we mustn’t downplay the problems it still faces, there are reasons for optimism – tales of development, invention and genuine stability.

One of those stories is of a confident and expanding film industry, one that’s in a far healthier place than it has been since… well, ever. While it’s too soon to be talking about ‘golden ages’, we can at least point to a generation of filmmakers who are in a position to make it happen.

But if we’re serious about African film then we should start by acknowledging the complexity of the continent. Whatever the aspirations of the various Pan-African movements, Africa is a combination of 54 countries, each with their own culture, history and experiences, and some of those countries are more film friendly than others. Most famously, there’s Senegal, which is where the story really starts.

Specifically, it begins with one man. Ousmane Sembène is famous as ‘the father of African film’ but that is but one of his claims to fame. Born in Dakar in 1923, he found his way to France after the Second World War and became first a stevedore at the Marseilles docks, then a Marxist and ultimately a novelist. Because he wrote in French, his books are not as well known in the Anglophone world but those who know about these things put him up there with Chinua Achebe and Ngugi wa Thiong’o.

While Sembène’s books were acclaimed by intellectuals, he was frustrated that they didn’t reach the people. Reckoning that cinema offered a better way to get his stories to a mass audience, he enrolled in film school – in Moscow, of course – and then returned to make the first film in Africa by a black director.

This was Borom Sarret (1963), showing the day in the life of a cart driver. It’s a short film – only 20 minutes or so – and obviously indebted to Italian neo-realism (or at least Bicycle Thieves [1948]). But it represented a seismic shift.

For a start, it’s set in an urban environment rather than the savannah that tourist-minded western directors liked to show. More than that, it prioritises an African viewpoint unmediated by any sort of benevolent white authority figure for pretty much the first time on film.

Sembène followed this landmark with another, the first feature directed by a black sub-Saharan African. La Noire de… (1966) also initiates one of the recurrent themes of African cinema; it’s about a young Senegalese woman brought to France when the colonial couple who she serves return home.

Many later African films would also show journeys to the colonialist heartlands but few would do it as potently as Sembène. And it remains pertinent: Sembène was working in a post-colonial context but the immigrant experience, and the attendant exploitations/ violations, has changed depressingly little over the years.

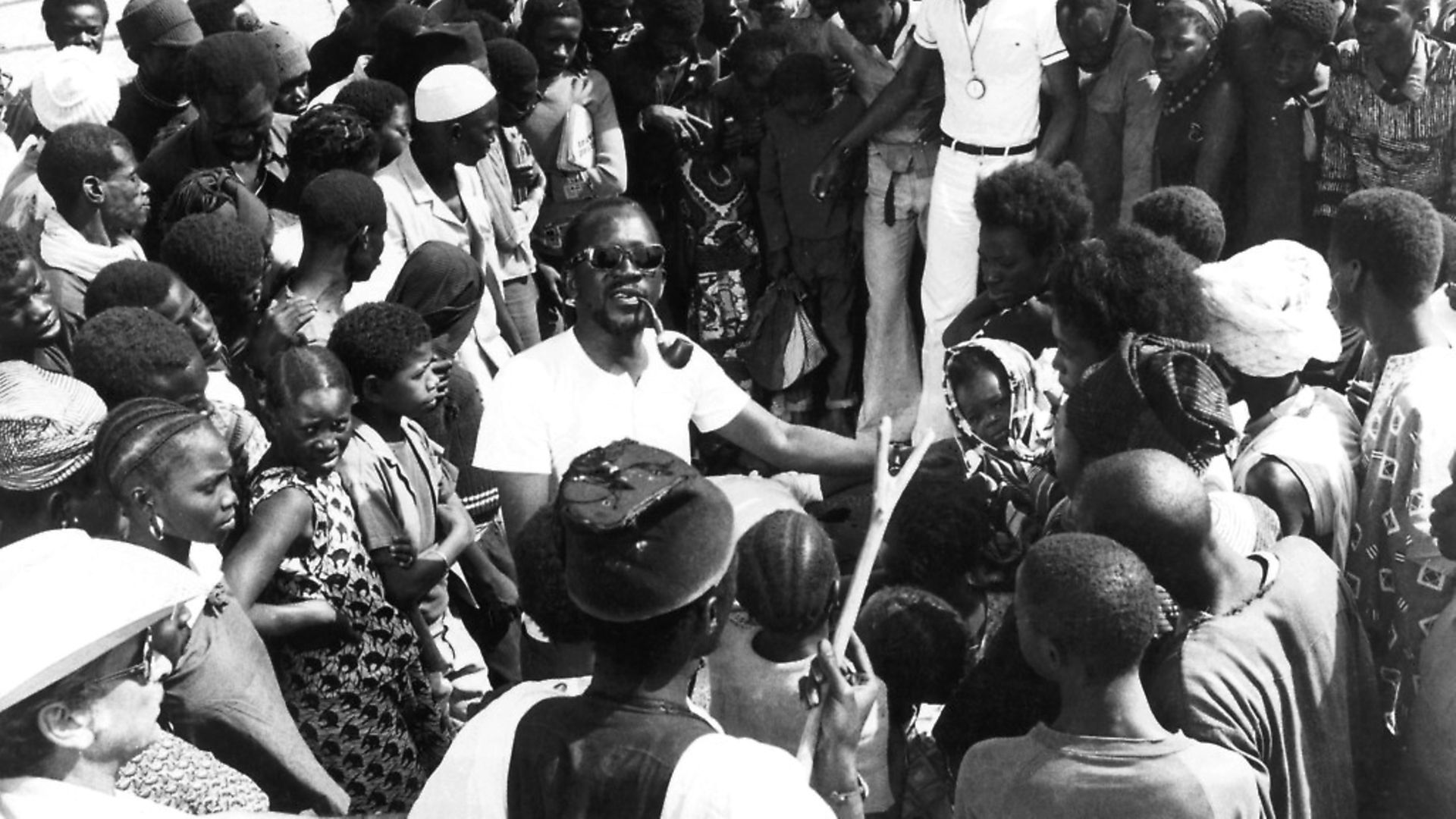

Sembène placed himself in the tradition of the ‘Griot’, the traditional West African storytellers, and never forgot he was making films for ordinary African people rather than European arthouse audiences, something well-illustrated by Xala (1975). It is a story about the kleptocracies that took power in Africa after independence and their various corruptions. Which all sounds terribly grand until you learn how Semebene addressed it: ‘Xala’ can be translated as ‘erectile dysfunction’, something that afflicts its main character, businessman El Hadji, who has been cursed by people he has ripped off.

It’s a broad, often bawdy, film and very funny too. But it shows the revolutionary’s disgust at how the promise of independence has been squandered by greedy men still in thrall to European mores. It’s also a very feminist film that recognises how unfairly women are treated and gives them room to attack patriarchal structures (‘there can be no progress in Africa if women are out of account,’ Sembène once said).

Sembène blazed a trail that others would follow, none more successfully than his fellow Senegalese filmmaker Djibril Diop Mambéty. His film Touki Bouki (1973) was the only African film to crack the most recent Sight and Sound critic’s poll top 100, where it made joint hundredth. It is a freewheeling – almost New Wave – film about a couple with idle dreams of leaving Africa for France. It’s so good that Beyonce and Jay Z ripped off imagery for it in a photoshoot. It portended great things… except Mambéty didn’t make his next feature, Hyènes until 1993.

Making films anywhere is not easy but in Africa it is harder still. State support is limited – films are a luxury item, one few governments can afford – and plutocrats have historically been more interested in indulging opulent lifestyles for themselves than in becoming patrons of the arts.

Budgets have usually been raised in Europe, either private money or public funds. (One reason that Africa’s Francophone countries have historically produced more films is because French governments have historically had a more generous attitude to state subsidy than the British.)

With that in mind, perhaps we shouldn’t complain about how few films have emerged from Africa but marvel at how many great ones have: a brief list would include things like Soleil O (1970, Mauritania), one of the best journey-to-Europe films. More fantastically, there is Yeelen (1987), from Mali, a quasi-folk tale that was the first sub-Saharan African film to compete in Cannes, where the well-liked Yaaba (1989, Burkina Faso) – in which a young boy befriends an old woman accused of sorcery – also premiered.

The most acclaimed African film of recent years was (probably) Timbuktu (2014, Mauritania), inspired by the Islamist takeover of the titular town and showing the full horror of what that brings – football? banned; singing? banned; forced marriage to jihadists? very much allowed.

It is a fine film, one that illuminates some of the darker chapters of the past decade, but it is again another film that deals with politics and issues.

This is something of a fixture of African cinema, at least those films part-funded by European money and premiered at European film festivals: socially aware and politically minded; the sort of stuff, in other words, that cater to a western liberal’s idea of what Africa is. (‘A scar on the conscience of the world,’ remember.)

It takes nothing away from the many excellent films mentioned above, nor the people who made them, to suggest that there might be other ways of doing things, and there is a new generation making that case.

Wanuri Kahiu is one of the most promising of these: her breakthrough film Rafiki (2018, Kenya) does indeed deal with social issues (in this case, a same-sex love story, which did not go down well in its conservative homeland, where it was banned) but don’t think that’s all she wants to do. ‘I’m not saying that ‘agenda art’ isn’t important,’ she related in a 2017 TED talk. ‘But it cannot be the only art that comes out of the continent.’

Others agree. One of the most interesting and encouraging features of the past 20 years or so is the development of a genuinely popular, genuinely commercial African cinema, one that began in, and is still centred on, Nigeria, enabled by digital technology that levelled the costs of production and distribution (on DVD).

The earliest of these ‘movies’ were unsophisticated action films, produced in volume at no great cost. But ‘Nollywood’ – as this industry was predictably dubbed – evolved. As Nigeria developed, so standards improved and budgets – raised from local, private sources – rose: a million US dollars might not sound like a great deal to spend on a movie but you get a lot of bang for your buck in Nigeria.

And now Nigeria’s GDP is the highest in Africa, ‘Nollywood’, is booming. No longer does its product go straight to DVD; cinema screens have proliferated in the last decade and they’re often filled by local productions of increasing ambition. Merry Men: The Real Yoruba Demons was the biggest domestic hit of 2018, and it’s worth discussing in a little more depth, and not just because it was one of the first Nollywood films to get a UK cinema release, something that will only become more frequent.

Popularity has never equalled quality, of course, and Merry Men probably won’t appeal to those who dig Xala. The title characters are four high-rolling playboys who use their various skills (including computer wizardry and devilish charm) to foil corrupt businessmen and distribute the proceeds to the poor. It’s light entertainment but that doesn’t stop it as being as deeply political as anything Sembène made, and not just because the bad guys are a corrupt politician and a profiteering government contractor (topical villains in a country where graft remains a serious problem).

But more important than that is the vision of success it offers. Poverty is shown but briefly; most of the film takes place in newly-built buildings, amidst luxury and conspicuous consumption. There are as many Apple-branded products as any Hollywood film and as much glamour too. This is an Africa rarely glimpsed in Europe, but it’s as striking a sign of confidence as one could hope for.

Confidence is visible elsewhere in African filmmaking. Isaac Nabwana makes films in Wakaliga, a suburb of Kampala in Uganda. There are no newly built buildings here and no Apple-branded products; Nabwana began making films for his own amusement, selling them on DVD in his neighbourhood (which – yes – he calls ‘Wakaliwood’). The trailer for one of them, Who Killed Captain Alex? (2010), was uploaded to YouTube and went viral. A star was born.

Critics sometimes talk about ‘punk rock movies’ or ‘DIY movies’ but Captain Alex – a low-budget action movie with questionable effects – deserves that label far more than any western indie. It cost around $200, with Nabwana making all the props himself and doing the effects – including an endearingly terrible helicopter – with computer freeware. And he’s a decent director: if the film’s dialogue sequences aren’t entirely successful, the all-important action is well done.

Nabwana’s follow-up Bad Black (2016) reveals him more fully as a filmmaker. This adds a demented voiceover that makes plain this is a comedy, and a very funny one at that: we meet ‘the Ugandan Schwarzenegger’ and ‘the American Van Damme’, the latter a token white dude turned into a fearsome commando by a small boy called ‘Wesley Snipes’. All this for, again, $200 or so.

Beyond the man himself, Nabwana’s story shows how technology can liberate filmmaking. Nabwana no longer has to scrounge around for small change to make his films, he can start a crowd funder (he has a Patreon too). Whereas before he flogged his DVDs door to door, now he can upload things on YouTube and get a global audience, not to mention profit from the ad revenue. Oscar-winning director Sir Peter Jackson started out making equally outrageous films in much the same way before he discovered Hobbits. It is not impossible to imagine a similar career trajectory for Nabwana.

For the first time, African newcomers have the same opportunities as those in America and there is nothing stopping more artistically-minded filmmakers following Nabwana’s lead. What’s more, there are more opportunities to get their work screened. The most important development in African filmmaking is the same one that has been so significant elsewhere: the arrival of Netflix.

Its business model depends on expanding and Africa is one of the territories where it is doing just that. And, just as it does everywhere, it is investing heavily in local content.

The first production from Netflix Africa ran into a minor controversy; Lionheart is a Nigerian film, directed by and starring Genevieve Nnaji, one of the continent’s biggest stars. When Netflix tried submitting it to the Oscars, however, to be considered as Best Film in a Foreign Language it was disbarred – it was reckoned a film almost entirely in English isn’t really in a foreign language. But it’s a measure of the Netflix muscle that anyone was even thinking about Oscars in the first place; to date, only one film by a black African director has even been nominated at the Academy Awards; Timbuktu. It’s only a matter of time before that changes.

A flourishing film industry in certain countries is not, of course, the same thing as genuine prosperity across the continent and we mustn’t sugarcoat things when so many challenges remain. But these films are a symptom of how much is changing and how fast. Just as importantly, they show that the continent’s people don’t have to be dependent on Europeans to flourish any more; African filmmakers are, finally, seizing their light.

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37