The Swiss held two important national referendums last Sunday. The first decisively reversed a previous one of 2014 which, by a wafer-thin majority, had sought to end freedom of movement of people with the EU, putting the country’s whole relationship with Europe in jeopardy.

The lesson for Brexit Britain, a Swiss friend tells me, is that “on big issues you should either allow for repeat referendums, so people can change their mind, or for none at all. If the people at large are going to take over the ultimate function of parliament, they need the same right as parliament to debate and decide on big issues every few years”.

A British opinion poll this week showed that 50% now think Brexit a mistake. Only 39% still support it. A referendum to rejoin the EU next January, rather than to go off the edge of the cliff at the end of the transition period, would probably secure a majority.

Denmark and Ireland tell a similar story of narrow first referendum rejections of pro-European policies being corrected by decisive pro-EU majorities second time round.

On European policy alone the Swiss have now held 13 referendums over the last half century. Ten have gone in favour of closer relations with the EU and three against, which reflects the general bias of Swiss sentiment about Europe, which is to get very close but not to the point of full EU membership.

Last Sunday’s other major Swiss referendum makes the point too. It was on granting two week’s paid paternity leave to fathers. Fear of a referendum defeat in the notoriously conservative alpine country led the Swiss government to delay this social reform, long introduced across the rest of Europe.

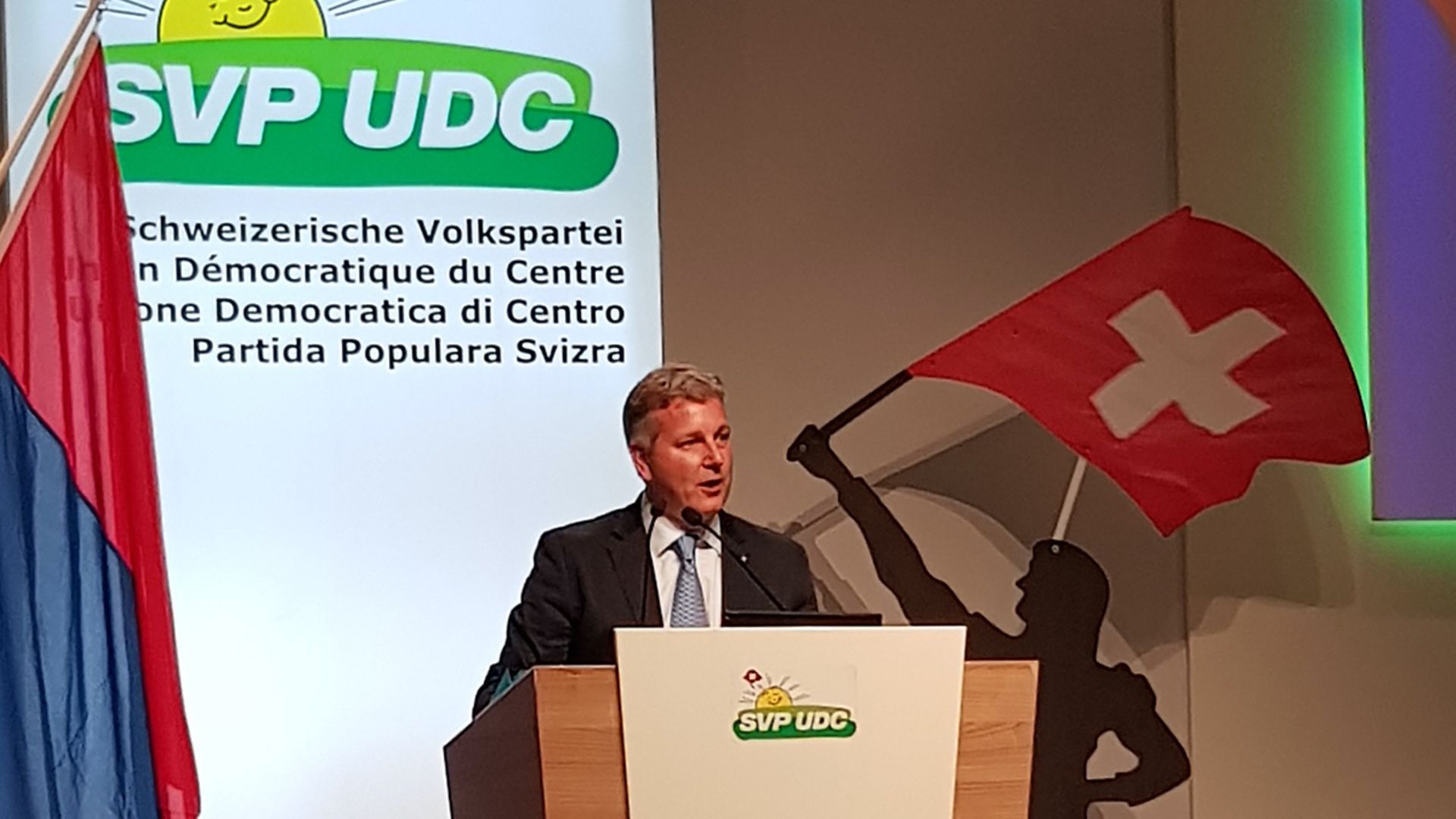

Diana Gutjahr of the populist Swiss People’s Party, leading opposition to the proposal, said: “We shouldn’t be financing things that are nice to have but not essential.” Whereas maternity leave was important “because a mother has to breastfeed and physically recover from childbirth,” the same “vital role” did not apply to the father, she added. The 40% who voted against paid paternity leave appear to have agreed with her.

All this goes back to Switzerland’s bitter experience, amazing in retrospect, with women’s suffrage. Swiss women did not get the vote in national elections until 1971, and not until the 1990s in the last of the cantons, because of referendum defeats. The previous federal referendum on giving women the vote, in 1959, saw it rejected by more than two to one by Switzerland’s men. It took 12 years to reverse this, in a two to one vote the other way.

I don’t relish the thought of 13 British referendums on Europe. The two so far have been horrendous enough. But to do the right thing for the country, its security and prosperity, we will probably need a third referendum, either on rejoining the EU or on a Swiss-style plan for a close relationship. The question is when.

In my view, the sooner the better. It can’t come until after the next general election, and even then only if the Tories lose, so it couldn’t be for about another six years at the earliest, which will be a decade since the fateful 2016 referendum. With a positive outcome it would still take several more years – probably into the 2030s – for a closer relationship with the EU to take effect.

Pro-Europeans therefore need to be campaigning from now for Britain’s opposition parties to go into the next election with a policy of negotiating a closer relationship with the EU, including the option of a referendum to rejoin.

It is depressing that the Lib Dems, the most naturally pro-European of all the parties, were persuaded by their leadership at their conference this week to make rejoining only a ‘long-term’, not a ‘short-term’, goal.

John Maynard Keynes, maybe the greatest Liberal in history, gave the compelling riposte to that. “In the long run we are all dead,” he famously said in the 1930s of attempts to delay implementation of his radical ideas to tackle unemployment. Maybe he had been talking to Swiss women campaigning for the vote.

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37