There might seem little obvious attraction in revisiting old ‘apocalypse movies’ in the current climate. But, says JAMES OLIVER, the genre actually offers a sense of reassurance you won’t find elsewhere

Strange times, right? Everyone seems to agree that ‘it’s like something from a movie’ but no-one can agree which one.

When Covid-19 first made its presence felt in the West, people reached for the obvious: Contagion, an extremely prescient film from 2011 about a hardcore respiratory infection that originates in China, rocketed up the Amazon charts, propelled by a curiosity about this strange new threat.

Now it’s actually hit us, things are changing – or ‘mutating’ as we should probably say now we’re all obsessed with viruses.

Ransacked supermarkets, and the behaviour of (some of) those who stripped them brought forth other analogies. ‘It’s like Mad Max’ is a frequent refrain across social media, referencing George Miller’s everyday tales of life in a post-apocalyptic wasteland.

This isn’t entirely fair. In Mad Max, characters fought for control of precious petroleum; we’ve only been brawling over bog-roll (so far…). But even so, we’re in uncharted waters right now. We’re looking for comparisons to make sense of what’s going on: that we’re looking at movies set during and after various apocalypses tells its own story about the contemporary mood.

There is no shortage of films for us to draw on. Cinema is very good at worst case scenarios. It’s ended the world hundreds of times, with many more near misses.

Most obviously, there’s the Bomb. The apocalypse movie scarcely existed before humanity gave itself the ability to destroy all life of earth, but quickly established itself as a reliable box-office draw.

You might think people would prefer not to spend their precious leisure hours dwelling on the possible destruction of the planet but apparently not.

Many of those movies disguised the nuclear threat; although mainly marketed at kids, the 1950s monster boom was a direct reaction to atomic weapons – famously, Godzilla is a rubbery metaphor for the horrors of Hiroshima.

However, there were films that tackled things head-on, tentatively at first (The World, The Flesh and The Devil, from 1959), then more vividly: On The Beach, from the same year, featured big stars (Fred Astaire! Ava Gardner! Gregory Peck!) trying to survive down in Australia after a nuclear exchange, without much success.

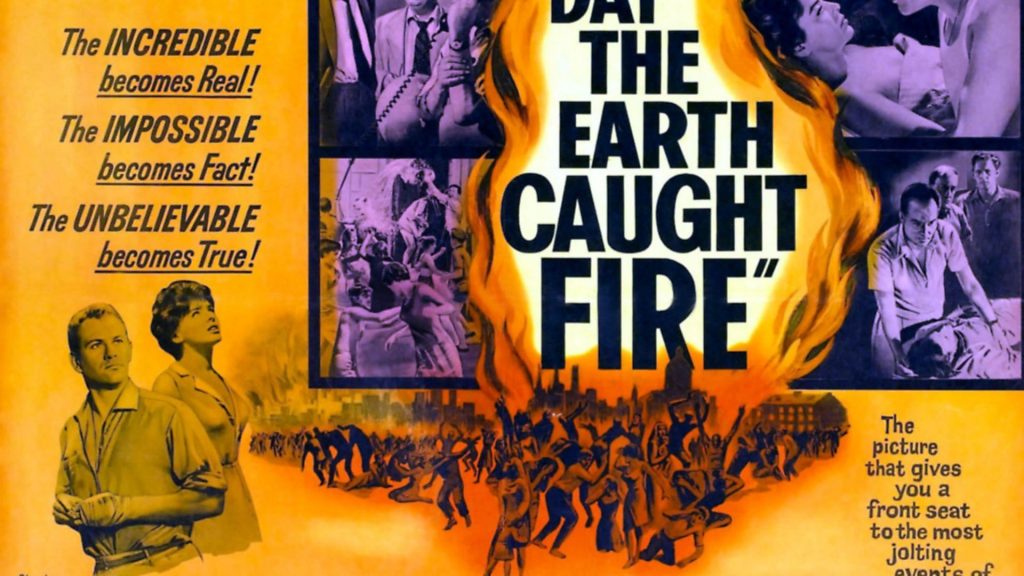

Now, most atomic age anxiety movies aren’t entirely relevant to our present situation (and that’s a positive! That’s something to hold on to!) Still, it might be worth looking at 1961’s The Day the Earth Caught Fire. Here, the globe gets knocked off its axis during a nuclear test, causing the temperature to rise inexorably. Far more disciplined and downbeat than most 1950s sci-fi, it is a film about climate change made decades before anyone coined the phrase ‘global warming’.

If it sometimes looks a little dated – a mad procession of beatniks and jazz musicians isn’t quite as transgressive as once it was – human nature hasn’t changed since it was made. We can still recognise the despair of the people on screen, the terror of ordinary folk faced with something they’re powerless to influence.

For all people were worried about the Bomb in the 1950s and 1960s, everything else (rising prosperity, rising social mobility, all that post-war gubbins) gave more cause for optimism. Truth be told, the apocalypse movie didn’t really get up to speed until that confidence started to curdle.

In 1969, at least partially inspired by what his country was doing in South East Asia, George Romero made a movie that set the tone for the next decade. This was Night of the Living Dead, a tremendously successfully (and equally bleak) horror film that depicted a society in collapse.

That collapse is caused by the dead rising from their graves to attack the living, although Romero – far more than the hacks who tried copying him – is very much alive to the social and political dimensions of this catastrophe, and about how people under pressure react (badly, basically).

While Night of the Living Dead was a low-budget indie, mainstream film embraced the apocalypse and thereafter with the same enthusiasm. In The Omega Man (1971), a biological weapon has done its worst, leaving big Charlton Heston as the last man standing and obliging him to fight off red-eyed-vampire-thingies (that’s the technical term) all by himself.

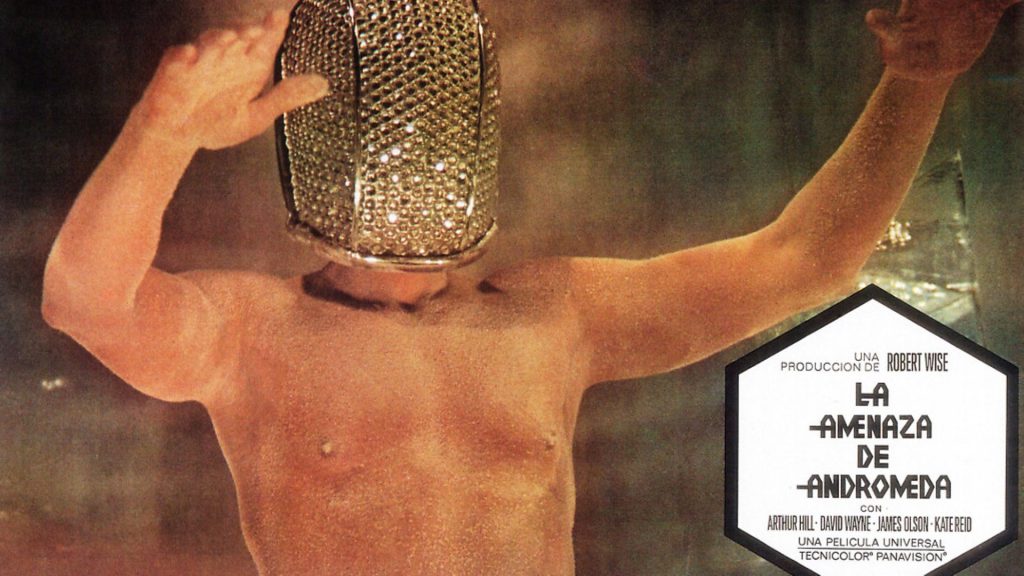

Given that it leaves most of the planet alive, The Andromeda Strain (also 1971) isn’t as pessimistic but this story of the fight against an extraterrestrial virus reminds us how delicate society is, and how ineffectual even our best science can be, not the most cheering thought at the moment. (Even before Covid-19 and SARS, viruses were a popular way to kill off large swathes of humanity. A race memory of the Black Death, perhaps, which did exactly that.)

Whereas science fiction of earlier years looked forward to a bright, shiny future, many 1970s films followed people trying to survive after some sort of collapse. In 1970’s No Blade of Grass, it’s environmental – a virus (another one) has done a number on plant life, which doesn’t leave much to eat. A Boy and His Dog (1975) and Damnation Alley (1977), meanwhile, rely on the good old fashioned nuclear destruction, torching the world and a good few of its inhabitants, leaving only isolated clusters of people.

And sometimes it’s more vague: neither The Final Programme (1973) nor Zardoz (1974), both of them British, fully explain what broke the world.

Whatever the causes for the desolation, the results are seldom pretty. If civilisation hasn’t actually collapsed in these films then it’s looking distinctly peaky, and Enlightenment values are surplus to requirements: Zardoz, for instance, concludes with what remains of higher culture chopped down by barbarians.

By showing how easily it can be swept away, all these films stress the fragility of our society. This is very core of the apocalypse movie; the genre isn’t so much about prediction as projection, extrapolating the terrors and the tensions of their times, which is why it tends to flourish in ages of anxiety.

In the 1970s, there were fuel shortages, financial shocks, terrorism and more: not quite end-of-the-world stuff but enough to show just how rickety our way of life is, and how little it takes to cause disruption.

And that, surely, is why the apocalypse movie flourished in the early 1980s, when Ronald Reagan ramped up the Cold War and nuclear panic was at its height. Mad Max (1979) is only the most famous of those: The Quiet Earth (1985) and Night of the Comet (1984) are smart survival movies set in (mostly) empty cities, while 1986’s Dead End Drive-In might look like one of the numerous Mad Max rip-offs that littered video stores of the time but it’s a good deal smarter and savvier than that, as though J.G. Ballard tried to make an exploitation movie.

Whether because of Reagan’s sabre-rattling and/or the failings of the Soviet system, the Cold War was over by the end of the decade. The apocalypse movie wasn’t though, probably because the collapse of communism meant we were aware of other things. Like climate change – Waterworld (1995) was an early (and not very good) response to that, set after the polar icecaps have melted (In 2008, Wall*E would tackle environmental issues with far more imagination and wit).

Then there were the more warnings about viral outbreaks: the one in 12 Monkeys (1995) wipes out 98% of humanity.

The strain in 28 Days Later (2002) isn’t that severe but does turn the infected into enraged zombies. Influenced by Romero’s films, it was also informed by the fuel protests of 2000 when the petrol pumps ran dry with distressing speed, and we realised how vulnerable supply lines were.

Mad Max comparisons were wheeled out during those protests too but by the time 28 Days Later was actually released we viewed them more benignly – almost nostalgically, in fact. We learnt on September 11, 2001, that there are worse things than petrol rationing.

Unsurprisingly, it’s been good times for the apocalypse movie since then, from high art (2003’s Time of the Wolf, written and directed by Michael Haneke) to low trash (Left Behind,from 2014 – with Nicolas Cage) and all points in between (It Comes At Night [2017], Melancholia [2011], The Rover [2014], 10 Cloverfield Lane [2016]…). The best must be Children of Men (2006), directed by Alfonso Cauron.

Taking place after some unspecified event has rendered our entire species infertile, it’s one of the few movies that shows everyday life after an apocalypse: the world grinds on and will do until everyone on it is dead, but everyone is angry, anti-immigrant sentiment is rife and there’s nothing at all to look forward to. (Any resemblance to the last few years in this country is purely coincidental.)

We live in apocalyptic times. Even before the current pandemic there was no shortage of existential threats, whether climate catastrophe, the rise of AI or global populism.

Hell, not enough is being made of the actual plague of locusts gnawing its way across Africa right now.

As depressing as all this is, apocalypse movies can provide their own reassurance. They reflect the terrors of their day and, in most cases, those terrors have passed. Soon enough that will be true of our current nightmare too.

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37