The Arts and Crafts movement provided a bridge from tradition and nostalgia to the modernism that was to follow. Few of its leading lights display this shift as sumptuously as Arthur Heygate Mackmurdo.

Between the Arts and Crafts pioneering work of William Morris and the lean soaring lines with floral motifs of Charles Rennie Mackintosh, a third and influential “M” helped define the look of late Victorian and Edwardian Britain, and influence style at home and abroad.

Architect and designer Arthur Heygate Mackmurdo (1851- 1942) is the subject of both a new book and a forthcoming exhibition at the William Morris Gallery in east London, that he helped found.

Responsible for a small number of important buildings, even though several are lost, he was also a founder of the influential Century Guild (CG). This collegiate and idealistic group would bridge the medievalism of Morris and his contemporaries and the Mackintosh look that edged others towards Art Nouveau and, ultimately, modernism.

Mackmurdo was born into a prosperous south London family. His father, whose business was in chemicals, was also interested in artists’ materials, which he displayed at the Great Exhibition in the year of Arthur’s birth.

The boy was found a pupillage with an architect’s practice, thriving in that discipline and championing conservation. While not a member of the Society for the Preservation of Ancient Buildings, founded by Morris, he shared its concerns.

He persuaded Sir Henry Meux to give a home to Sir Christopher Wren’s endangered archway Temple Bar and stood up for Wren’s City churches whose obscure locations and neoclassical design had rendered them perilously unfashionable in Victorian London.

Hugely influenced by the art critic and idiosyncratic arbiter of taste John Ruskin, he assisted the great man on a trip in 1874 to Italy, the country that was to have the greatest influence on the Century Guild.

The CG, which incorporated its obligingly curving letters into many of its own designs, was a hub of artists across many disciplines with, at its centre, Mackmurdo, and the multi-talented aesthetes Herbert Percy Horne and the Reverend Selwyn Image.

Drawn together by a combination of art appreciation in its broadest sense, open-mindedness and concern for social reform, the Century Guild outriders rode a wave of exhibitions that, in the wake and in the manner of the Great Exhibition, showed alternative ways of living.

With three complete room displays, starting with a music room in 1885, they rethought every decorative detail and piece of furniture including a piano, designed by Mackmurdo.

Music was to be a strong partner in a movement that was at first glance design-led, but which also incorporated poetry and prose. Selwyn Image who, with satisfying nominative determinism, was the affable face and voice of the Century Guild, drew no lines between art’s many forms.

“Music is Art, Acting is Art, Dancing is Art, Literature is Art,” he declared in 1887, while encouraging householders to turn their back on the mass-produced interiors found on Tottenham Court Road and exercise their own taste.

The vehicle for this manifesto was a beautifully produced magazine entitled the Hobby Horse, its name a reference to Laurence Sterne’s Tristram Shandy. The galloping knight symbolised the quest for higher things.

The first issue, in 1884, included a lecture on art by Image, a paean to the National Gallery (“a collection finer than any in the world”, wrote Mackmurdo), a music review and a 12-page editorial.

Its very high production standards with intricate drop capitals and elegant tail-pieces – illustrations at the conclusion of an article – were not every reader’s cup of tea, and this was the first and last Hobby Horse, for the time being.

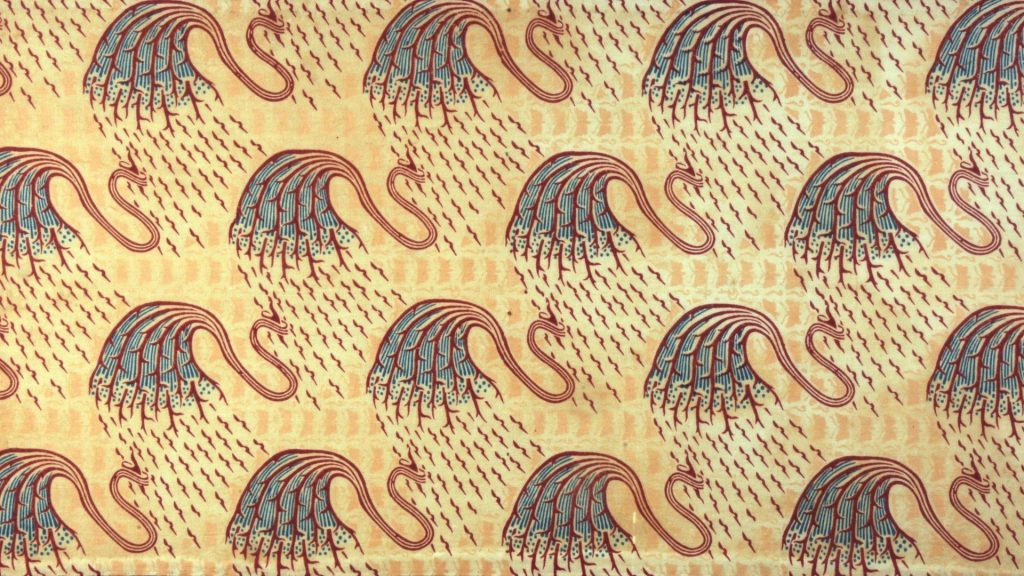

But interest in the music room at the International Inventions Exhibition brought to a wider public the characteristic palette of yellow and cream, Century Guild fabric designs with tightly wrought patterns and repeats, often with subjects from the natural world, and inventive cabinet-making.

And in 1886 the Hobby Horse rode again, with a new ‘first’ issue. The content included an essay on painter Ford Madox Brown, a review of Dante Gabriel Rossetti at the Royal Academy, and an essay on Keats by Oscar Wilde.

Wilde was a friend of the Century Guild, and one of the many droppers-in when live/work premises were procured in London’s creative quarter, Fitzrovia. It was to a house designed by Mackmurdo that the writer would turn in the first instance upon his release from prison in May 1897. This was the Bloomsury residence of another enlightened clergyman, Stewart Headlam. Founder of the Church and Stage Guild, Headlam took issue with the church’s disapproval of entertainment, protesting that his East End parishioners were “made for nobler things… than mechanical works” and chiming with the Century Guild’s manifesto that all arts were equal and connected.

At the Liverpool International Exhibition in 1886, the Century Guild had its own stand, and also undertook a display for a tobacco company that was exuberant in its celebration of the commodity.

Perhaps more socially relevant was the Mackmurdo house that was proudly costed at a mere £620. The figure was significant: to build a typical London terrace, poorly lit and ventilated, cost £600.

Mackmurdo with his design showed that with an extra £20 and a lot of imagination it was possible to create a more spacious home. His example, Brooklyn, in Enfield, north London, had enough rooms for parents and children, and featured external statuary of boys and girls.

Gaps between floorboards were sealed and there were few dust-gathering surfaces. The message was clear: here is a family home, and no servants are obliged to live in.

For the brewer Henry Boddington the Century Guild set to work on Pownhall Hall in Wilmslow, Cheshire, now a school. Decorative additions included a frieze designed by Image, in which the arts are entwined as ribbons on a naked figure.

The Hobby Horse limped on, with a readership in the 200s and 300s, but Mackmurdo, whose architectural practice was clearly subsidising the publication, tired of this drain on resources.

He also lost money in a salt-water therapy enterprise, both designing and investing in the Brine Baths Hotel in Nantwich, Cheshire. And he fell out, possibly over money, with his life-long friend and colleague Horne, who decamped for his beloved Italy, selling his art collection to pay for his new life in Florence. His home there is today the Museo Horne.

Mackmurdo, now married to a cousin, embraced the new movement to create utopian garden suburbs. At Beacon Hill in Essex, where a community was to share, among other amenities, a bakehouse, laundry and dairy, he designed several buildings, including Great Ruffins, a Wren-influenced country house with many functions. He lived at Beacon Hill himself, until his death at 91.

The art historian Nikolaus Pevsner, not always easy to please, was unstinting in his praise for the architect. “Some of his works between 1880 and 1890 were more adventurous than those of any other British architect during that decade,” he wrote, adding, with the authority of one who has travelled widely, “Which is tantamount to saying the work of any European architect.”

Arts and Crafts Pioneers: The Hobby Horse Men and their Century Guild, by Stuart Evans and Jean Liddiard is published by Lund Humphries (£35). Within the Reach of All: The Century Guild runs at the William Morris Gallery from May 18 to August 31, Covid measures permitting.

What do you think? Have your say on this and more by emailing letters@theneweuropean.co.uk

Activist artist

Like many of the leading figures of the Arts and Crafts movement, Mackmurdo was a committed socialist. At the turn of the century, he settled down in the Essex countryside and, scaling down his earlier artistic activities, devoted much of his time to writing socialist pamphlets, including one on electoral reform.

As well as socialism, the Arts and Crafts movement was also associated with ‘dress reform’ –the promotion of more practical and comfortable clothing than fashion permitted – the campaign for garden cities and agrarianism. It was also closely linked to the English folk song revival of the period.

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37