Looking back at the astonishing career of a man who took US embroilment in the rest of the Americas to extraordinary lengths.

Ask someone in Central America to name a figure from US history and there’s a good chance they’ll say William Walker. Of course, if you mention that name to most Americans, you’ll receive a blank look for your trouble. But in Belize, Honduras, Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala and, most especially, Nicaragua, the people know all about Colonel Walker. Just don’t expect to hear anything good about him.

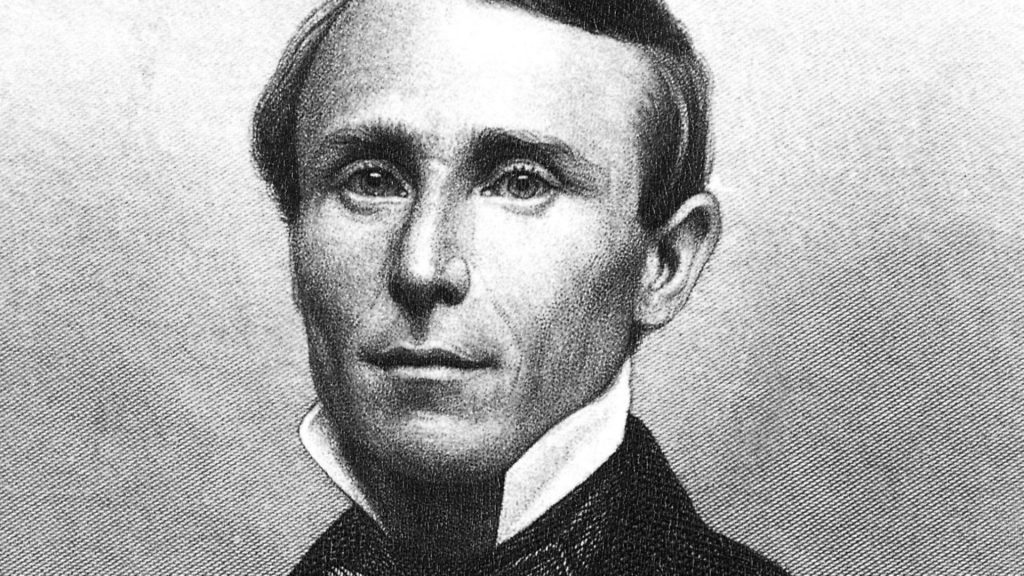

In the world of the renaissance men, William Walker was king. Before he got ideas above his station, Walker – born in Nashville, Tennessee, in 1824 – studied medicine at the Universities of Edinburgh and Heidelberg, qualified as a doctor aged just 19 in Philadelphia, practised law in New Orleans in his early twenties, bought a newspaper, the New Orleans Crescent, and appointed himself editor.

During this era, he also had the romantic good sense to fall in love with Ellen Martin, a deaf mute rumoured to be the most beautiful woman in the whole of Louisiana. Tragically, Ellen would die of yellow fever before the couple could marry, a tragedy from which Walker would never recover.

Seeking new purpose in life, Walker set up shop in San Francisco. There he busied himself writing for local newspapers and fighting a series of duels. His first taste of national fame came in 1851 when, as editor of the San Francisco Herald, Walker had his honour impugned by William Hicks Graham, a gunslinger-turned-court clerk who objected to the way he had been portrayed in Walker’s paper.

The confrontation took place on January 12, 1851 and ended in farce with Walker forced to concede defeat when Graham hit him in the thigh, the newspaperman’s lack of familiarity with revolvers rendering him incapable of firing a shot. An incident that could easily have made a laughing stock of the vanquished, Walker instead used the Graham duel as proof that he couldn’t be killed by gunfire, the first of many myths that would spring up about ‘the Grey-Eyed Man Of Destiny’ as Walker took to calling himself.

With its peripatetic population of seamen, adventurers and soldiers of fortune, San Francisco whetted Walker’s appetite for adventure further afield. Come the autumn of 1853, he and a band of pro-slavery, manifest destiny-obsessed reprobates headed to Mexico bent on founding the Republic of Sonora, in territory now forming part of Mexico, which Walker hoped would provide the US border with protection from Indian invaders.

Admirable in the breadth of its ambition, Walker’s Mexican expedition was undone by an almost complete lack of planning and support. Forced back across the border, the newly-promoted Colonel Walker – it was he who did the promoting – was put on trial for violating the 1794 Neutrality Act. The starstruck jury acquitted him in the time it took Walker to sign 12 autographs.

One of the keys to understanding William Walker and his not-so-excellent adventure is the extent of his fame in the United States. In the 1980s, when the English film director Alex Cox came to make his movie about Walker (more of which later), the fact he knew so little of the colonel surprised him even more when he discovered how big a name William had been in the 1850s.

“He was the most popular man in America,” Cox later wrote. “Had Time magazine been in existence, he would have been its Man Of The Year. He was certainly more widely celebrated than the then president Franklin Pierce.”

Walker owed his popularity in large part to his extraordinary self-confidence and vision. While editing the New Orleans Crescent, he published a serial in which he described his sense of destiny and his conviction that he had been chosen on high for a special mission while on Earth; “Unless a man believes there is something great for him to do, he can do nothing great. It is natural for a man so possessed to conceive that he is a special agent for working out into practice the thought that has been revealed to him. To his hand alone can be confided the execution of the great plan that lies perfected in no brain but his. Why should such a revelation be made to him-why should he be enabled to perceive what is hidden to others-if not that he should carry it into practice?”

Of course, it didn’t hurt that Walker had the ear of transport magnate Cornelius Vanderbilt. The self-appointed ‘Commodore’, as he was publicly nicknamed, had long harboured ambitions of establishing a transport route across Nicaragua – in the days before the Panama canal, one could either traipse goods across Central America or waste weeks and risk everything sailing round Cape Horn. With Vanderbilt’s money in his pocket and 58 mercenaries under his command, the colonel headed south in pursuit of a new career, that of a filibuster.

From the Spanish filibustero – pirate – the term filibuster is now almost exclusive to the world of politics, to indicate a politician delaying or preventing a course of action. In the 19th century, however, ‘filibuster’ became the label given to anyone who embarked on unauthorised military action against a foreign state with an eye to stoking or supporting a local uprising.

With more recent filibusters including the Argentine scrap metal dealers who invaded South Georgia ahead of the Falklands War, William Walker is the poster boy for the activity, one that governments often turn a blind eye to, especially if the buccaneering actions in question might benefit them in the long term.

Arriving in Nicaragua in the early summer of 1855, Walker and his ragged band of ‘Immortals’ – the man certainly knew a thing or two about branding – rose to power through exploiting the country’s civil war tensions. Siding with the Democratic Party based in Leon, the second largest city in Nicaragua, Walker struck out at the ruling Legitimist Party, located in Granada, the oldest European city in the Americas. The colonel led his men through a morass of skirmishes, the culmination of which saw him acknowledged as the legitimate president of Nicaragua by none other than the US’s own head of state, Franklin Pierce. Walker had been in the country barely a year.

As quickly as he took power, Walker seemed determined to fritter it away. Like all the best megalomaniacs, he insisted on documenting his every exploit – naturally, he also took referring to himself in the third person. Whether you read Walker’s memoirs or Albert Z Carr’s excellent biography, you’ll come no closer to understanding why the new president did such universally unpopular things as reinstating slavery; Nicaragua having abolished the practice way back in 1824.

He also succeeded in antagonising Vanderbilt by siding with CK Garrison and Charles Morgan, employees of the commodore who set out to betray their boss. Add to this the unwanted attentions of Costa Rica and Honduras, each of whom feared Walker might next train his guns upon them, and it’s no great surprise to learn that Walker and what remained of his disease-ridden degenerate army were repatriated to the United States on May 1, 1857. His presidency spanned less than 12 months.

Were we talking about the world of the sane, his story might have ended here. Alas, when Walker-mania broke out upon the colonel’s return to New York, his appetite for adventure spiralled out of control.

A return to Central America was inevitable, as was the fact that the expedition would end badly. This time his target was Honduras, where British settlers were at odds with the ruling government over the possession of the island colony of Roatan. Once again, Walker hoped to exploit existing rivalries. However, he reckoned without the British navy, who were keen to maintain stability in the region, what with both the Mosquito Coast and Belize (then British Honduras) both under the rule of the crown. It fell to Nowell Salmon – a sailor who had won a Victoria Cross at the Siege of Lucknow – to arrest the colonel and turn him over to the local authorities. On the morning of September 12, 1860, Walker was killed by a firing squad in Trujillo, Honduras. He had celebrated his 36th birthday the previous May.

Since both history and America tend to venerate winners, the legend of William Walker quickly evaporated. By the end of the Civil War in 1865, the best the colonel could hope for was an occasional mention in the footnotes. His resurrection would come in part through pop culture – firstly via a throwaway reference in Gone With The Wind, then later courtesy of Alex Cox’s Walker (1987), a wonderfully warped account of the colonel’s Latin American escapades.

Starring the never-better Ed Harris in the title role, with Marlee Matlin as Ellen Martin and an unchained Peter Boyle as the bullying Cornelius Vanderbilt, Walker is a film with plenty to say about American attitudes towards Latin America during the Reagan era.

Anachronisms as diverse as Zippo lighters, glossy magazines and even helicopter gunships make it very apparent that Cox was more concerned with the – democratically elected – Sandinistas and the – US-sponsored, right-wing – Contra rebels of the 1980s than with rehashing the Legitimist/Democratic party dispute of the 1850s. At the time the only American studio film to have been shot in Nicaragua, Walker bombed at the US box office to the surprise of absolutely no one. It’s reputation, however, is enhanced every time the US turns its eyes to Latin America, as should the weight of William Walker’s cautionary tale.

For, with Venezuela front and centre, one wonders whether anyone will bother to recall what happened the first time an American believed he knew what was best for his neighbours to the south.

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37