Beijing’s Belt and Road Initiative is making deep inroads into Europe, and the continent’s leaders urgently need to understand the threat it presents.

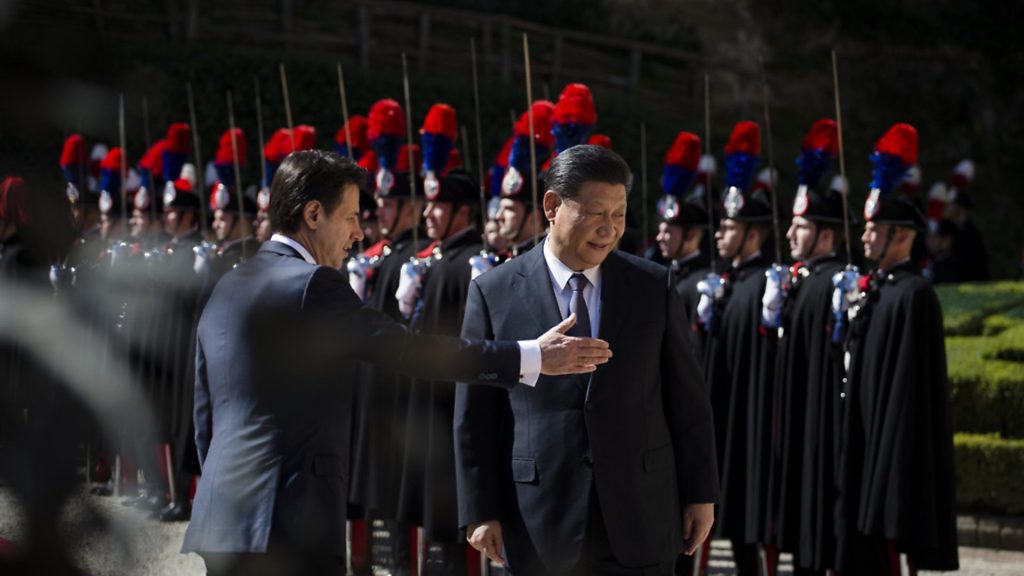

(Photo by Christian Minelli/NurPhoto via Getty Images) – Credit: NurPhoto via Getty Images

The all-consuming nature of Brexit in Britain makes it hard to believe the EU is not exclusively focused on it too. But, for many other Europeans and their leaders, the UK’s debacle is a frustrating distraction from other vital matters. One of the most crucial issues for Europe’s long-term future is the development of a new strategy for its relationship with China.

The stark recent description of China as a ‘systemic rival’ by the European Commission’s foreign policy arm shows how seriously this challenge is now being taken.

Until now, China’s astounding economic progress from impoverished backwater to burgeoning superpower has been largely seen as a bonanza for European export businesses and consumers seeking cheap and abundant products. But China has long since moved on from being the cut-priced workshop of the world.

Over recent years, Beijing has been using its economic clout to expand its global influence. It mostly does so stealthily, in keeping with the wisdom of Deng Xiaoping, the former premier and leading architect of China’s rise, who counselled ‘secure our position; cope with affairs calmly; hide our capacities and bide our time; be good at maintaining a low profile; and never claim leadership’.

Chinese companies have acquired swathes of businesses and control over crucial infrastructure across Asia and Africa. This has mainly been achieved with state financial backing and in close coordination with government plans. Many projects come under the umbrella of Beijing’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), a colossal multi-billion-dollar programme of constructing China-centric trading routes across large swathes of the globe.

China’s programme of power projection is now accelerating rapidly and directly targeting Europe. Chinese firms have taken control of major infrastructure such as the ports of Zeebrugge on the North Sea and Piraeus in Greece, a strategic gateway to Europe from Asia, located just across the Mediterranean from the Suez Canal, and. The Chinese have significant shareholdings in at least ten other major European ports.

A substantial transport hub, notably for overland rail, has been established by China in Duisburg, a struggling former steel city well-located by the busy Rhine waterway and in Germany’s populous industrial heartland, the Ruhr.

Meanwhile, the ’16+1′ initiative China launched in 2016 aims to intensify its cooperation with 11 eastern and central European EU member states and five EU-aspirant Balkan countries.

China has defined three priority areas for economic cooperation with the ’16+1′ group: infrastructure, high-tech industries and green technologies, and is already establishing big stakes in some of the countries concerned.

Perhaps the biggest and highest profile (contrary to Deng Xiaoping’s advice) Chinese coup so far is persuading Italy’s populist coalition government to sign up to the BRI. Italy is breaking ranks by becoming the first G7 nation and EU founder member to do so.

What is so bad about all that, some will ask? After all, the pattern of these Chinese investments indicates a focus on locations that are struggling economically and need all the investment they can get.

This is a fair question. Europe’s failure to spread its wealth sufficiently is a self-inflicted weakness that it needs to address. But the worries about China’s growing reach into Europe are justified. Building influence over Europe’s more vulnerable regions and nations puts China in a position to ‘divide and rule’. There are certainly valid reasons to fear Beijing will exploit economic dependence to assert political dominance.

In the parts of the world where it has advanced further, China has routinely used the BRI as a backdoor means to seize control of yet more strategic infrastructure. Loans are granted to the partner country that cannot be repaid and the assets are then taken by China instead as collateral.

There is a growing pattern of BRI projects coming with a Chinese military presence attached. Chinese-acquired commercial ports in Djibouti in the Horn of Africa, Pakistan and Sri Lanka have quickly become Chinese naval hubs too. Chinese naval ships have recently begun calling in at Piraeus.

China gaining a military foothold in Europe is a serious cause for concern because China cooperates closely with the most immediate threat to European security, Russia. The pair already conduct joint naval patrols in the Mediterranean.

National security risks abound in other ostensibly commercial transactions. The Huawei company is now the world’s largest supplier of telecommunications network equipment and already has a strong presence in Europe. America’s intelligence agencies, and those of several other Western allies, believe the Huawei’s murky ownership structure masks closer ties to the Chinese state than the firm’s managers care to admit.

Internally, China has become arguably the most intrusive, hi-tech surveillance state the world has ever seen. The US government has taken a series of steps to block Huawei from US telecoms markets. Australia and New Zealand also banned it last year from building 5G communications networks on their territory. Europe must also now consider whether it is wise to allow Huawei and other Chinese companies to become a central player in Europe’s next generation of IT infrastructure.

After all, distinguishing Chinese commercial interests from Beijing’s global power aspirations is almost impossible. Nationalist sentiment has often been stirred up by the state to decimate Japanese and South Korean companies’ investments in China, when their governments have displeased Beijing in some way.

Beyond East Asia, China frequently threatens trade disruption to pressurise countries into taking its side in its disputes with its neighbours and acquiesce to its wishes in global forums such as the United Nations.

Countries are regularly bullied when they criticise China or offend the Chinese state’s sensitivities. Norway was punished with severe trade restrictions for six years after the Oslo-based Nobel Prize committee gave an award to the Chinese human rights activist Liu Xiaobo in 2010. In 2017, China prevailed upon Greece to block an EU statement criticising its crackdown on dissidents and civil society activists. These attacks on small European nations can be seen as China testing the boundaries.

For Europe, finding the balance between accessing the economic opportunities China’s rise undoubtedly provides and avoiding subservience to Beijing is a complex challenge.

The strategy paper currently being considered by EU leaders focuses particularly closely on taking steps to compel China to level the economic playing field. Europe widely champions and practices free trade and open markets, including for public procurement. China rarely reciprocates and curtails European access to its marketplaces in multiple ways. Rectifying this unfair situation matters for its own sake. Even more importantly, equalising the economic balance of power will protect Europe against Chinese political pressure.

Whatever final strategy is produced, the process itself highlights one of the great benefits the EU provides. By combining the strength of 27 mostly small and medium-sized nations, it becomes one of the few powers weighty enough to deal with China on equal terms. Conversely, few foreign policy issues more brutally expose the folly of Brexit Britain’s quest to render itself weak, isolated and vulnerable.

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37