Liam Neeson’s comments have given license to others to expound extreme views

One of the more embarrassing stories my late mother would relate about my childhood concerned one of her friends. This lady, it seems, really mystified me. I could not understand why her dress stuck out in front.

I would ask my mother over and over, but even at the age of three I knew that she was putting me off. Then, Mama would later recall, I decided to investigate and get the answer myself.

I always stood or sat next to my mom when her friends came over because I was a talkative, inquisitive kid and always liked to listen in. During one visit, she suddenly realised that I was nowhere to be found.

She looked around and then saw me: down on my knees looking up under the dress of her friend. I wanted to see – because I wanted to see.

Of course, her friend was pregnant, but I wanted what I wanted. I was uncivilised.

Everyone who has raised a child knows that they have to be taught, punished and rewarded in order to learn civilisation: that collection of manners, mores, etc. that we use in order to live together in relative peace.

Babies and toddlers do exactly what they want and they are wonderful models of what we humans essentially are: uncivilised. Babies take food off other people’s plates. Why? Because they’re hungry, or just because they want to.

If they understand that this is forbidden, their responses run from mischief-making to rage to violence. We calm them down, and/or put them in a situation in which they come to understand that their behaviour is not acceptable. It is uncivilised.

Most of us do not have to have a family discussion about this. Civilisation is what mothers and non-mothers impart to babies and children. And in the last 40 years, fathers have become a part of this work, too. But it is work.

When I was a teacher, I would almost crawl home every afternoon after my class of five- and six-year-olds. Every day was a battle to civilise them, bring them into human interchange.

It was worth the exhaustion, but these children, on the cusp of their lives, taught me, too. They taught me about how fragile our system of courtesies and communications are; how they can fray and break and vanish in a heartbeat; that deep inside of us are not animals – most animals do not do the horrific things that we humans do – but violence. Pure and sheer violence.

That violence was once noticed by a bunch of scientists in our cousin species: the chimpanzee. At a reserve in Kenya, they observed a group of them suddenly leaving their compound en masse and heading for another chimp stronghold. They entered and started a fight. After they had beaten everyone to a pulp, they returned to their space. A few days later they did the same thing; won the fight; and this time took a bit of territory.

The scientists understood all of this as just what it was: violence. The violence of the species. Like we are.

Civilisation is a system of norms, conscious or unconscious, through which we humans literally live. It involves strictures against taking other people’s property just because we want it and we can; taking other men, women and children and making them our own just because we want to and we can.

Civilisation conjoins us not to harm those who do not look, smell; eat or talk like us. We do not immediately put these ‘strangers’ to death, but we learn to be with them; work with them; live close to them, even marry them.

No one applauds a person, in a civilised nation, because the person killed an innocent out of anger or fear. That perpetrator is usually, at the very least, brought before a court.

But our world now – a world in which all opinions are equal, where factoids compete with real facts, where there are websites employing techniques to voice-over a real person’s words, therefore distorting and destroying the speaker’s words and image and reputation and even their very life – is in danger of losing civilisation. Because it is always a fragile thing. Post-First World War Germany, a culture of high art and commerce, taught us that. Nazi Germany was the triumph of the irrational and the uncivilised. Its spectre is always not far away.

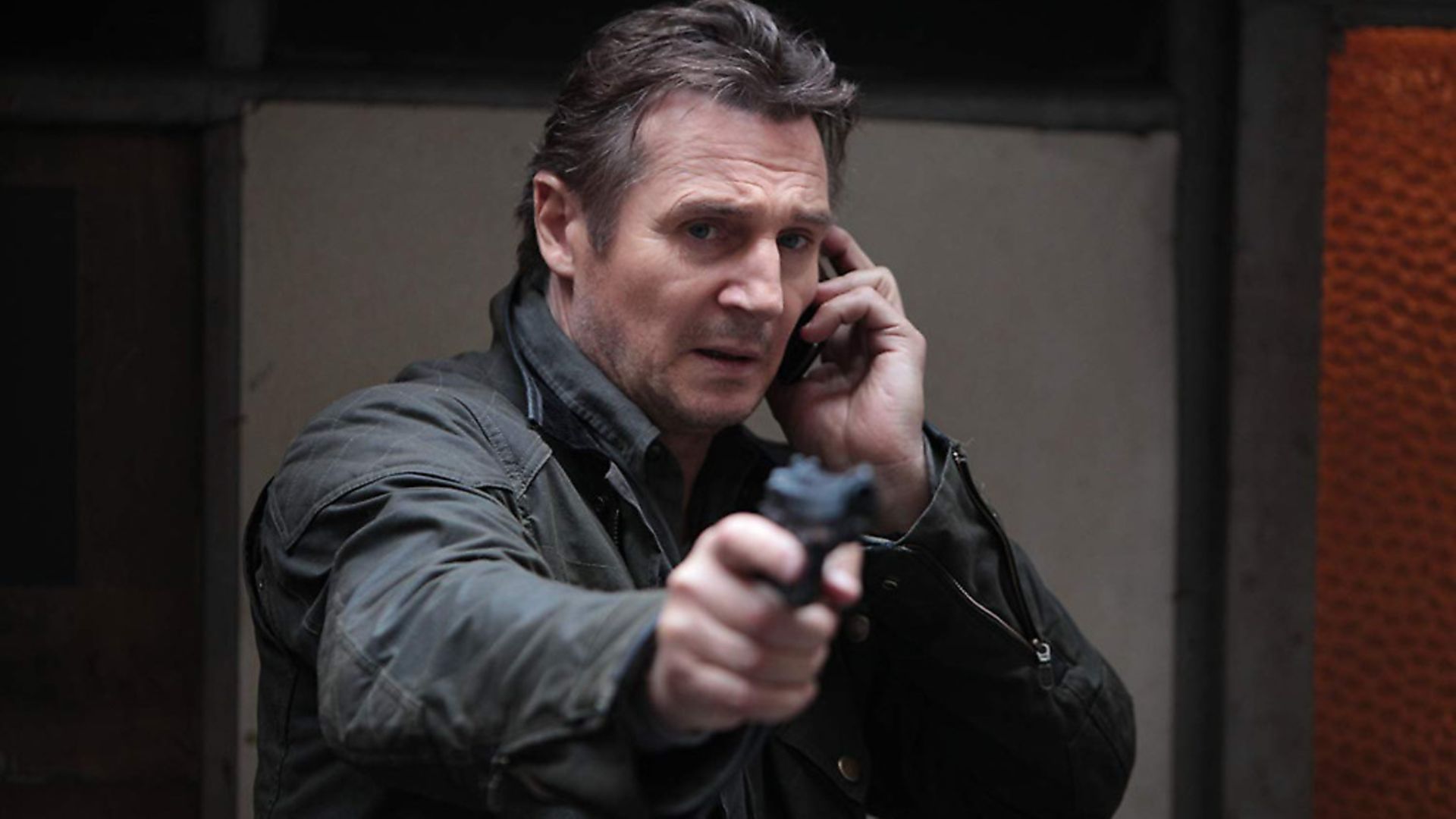

As someone who is in the theatre, Liam Neeson’s recent ‘confession’ about wanting to ‘kill’ a ‘black bastard’ out of revenge for the rape of a friend, sounds to me like something called ‘actor’s memory’.

A good actor – and Neeson is indeed that – stores thoughts, impressions, experiences and what-ifs in the mental toolbox of their craft. Every actor worth anything has this.

At first I thought that his admission of wanting to commit random racial violence was true. But now, I am not sure. This does not mean that he is a liar and I really do not believe that he is a racist or a bigot.

I think, from my experience working with actors, that Neeson went to his workshop, opened his toolkit of ‘people’ and out came the ‘racist avenger’. He has opened a Pandora’s Box of ignorance and uncivilisation.

Of all the people who have responded to his tale, praising his candour, his courage, even suggesting he get a medal for saying what other people will not, it is the response of people of colour – especially people of African descent – that have been the most dismaying.

Neeson talked of wanting to ‘kill’ a ‘black bastard’, and those last two words alone have shown his insensitivity to the world around him. But that black celebrities, in particular, thought that he should be given a pass is shocking.

His words provided an OK to those who, unlike him, are out to do real random, racial violence. Like the folks in the Deep South during the Depression who sent my late father to the north when he was a boy, because to be a young black man there was too dangerous. Every person of colour in the west has a story like this or knows one. To forget or overlook that history is a crime against memory. How can any of us forget the murder of Stephen Lawrence, killed because he was a black man who was alive and living his life?

And how can we forget, too, the white man who saw him dying, and knelt down and whispered in the dying young man’s ear some words of comfort so that the last words he might hear were not racial epithets?

That was an act of civilisation. In the face of possible violence done to him, a man knelt beside a dying stranger to help him leave this life in peace. Let us not for a moment be fooled by our codes of politeness, etc.

It is a veneer. A fragile one.

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37