BONNIE GREER explains how Phil Collins and Ethel Waters helped her to escape the herd.

One of the ways that I use to cause a pause in conversation is to announce that I was usually the only black kid at Genesis concerts in the 1970s.

It is always amusing to watch the edifice, the narrative, that a person has constructed about you crumble before your eyes. My revelation, of course, goes against everything that the conversant has brought to the table about me. It undermines their safe world. Their assumptions.

Now, if I want to be merciful, I explain that I was there to hear Phil Collins. Not the Phil Collins of the trembly, Peter Gabriel-lite 1980s-style of Against All Odds, or whatever he was singing in that most dreadful of decades.

I was there, back in the day, in various stadia, because Collins was a simply supreme rock drummer. Ginger Baker, of Cream – the Eric Clapton supergroup – was the king, but Collins was the crown prince, the magician who helped erase the spectacle of Peter Gabriel on stage, prancing about in his faux-Dada attire.

Rick Wakeman dressed like a second-rate actor auditioning for a Disney movie, and drove the organ like the pro he was. But it was Collins who made me sit there in my big Afro and beads, waving my candle, too. His solo in the band’s epic The Lamb Lies Down On Broadway, along with the film The French Connection, caused me to leave my hometown and move to the Big Apple.

Manhattan was as broken and dirty and dangerous as his drum solo implied and so, in a sense, because I chose not to stay in my ‘Black Student Union’/’Black Power’ box in relation to his band, I found something that expanded me.

I could dissect the stories in my head; look at my childhood in a rough ghetto neighbourhood – in which, at times, I fell asleep to the sound of gangs outside my window – and see something bigger, something universal.

It is too often our refusal of adventure, of danger, of going out and being blind-sided that is creating the boxes and silos that we live in now.

I don’t mean to imply that the danger of the guy I saw over Christmas, standing on the edge of a wall overlooking the Mediterranean in order to get a great selfie, is the way to escape the box. That guy courted danger in order to upload it; in order to get hits and follows. Approval from others.

The irony is that if he had fallen, his picture would definitely have gone viral without a doubt. After his picture-taking was over, he joined his dress-alike, look-alike crowd. He stayed in his world.

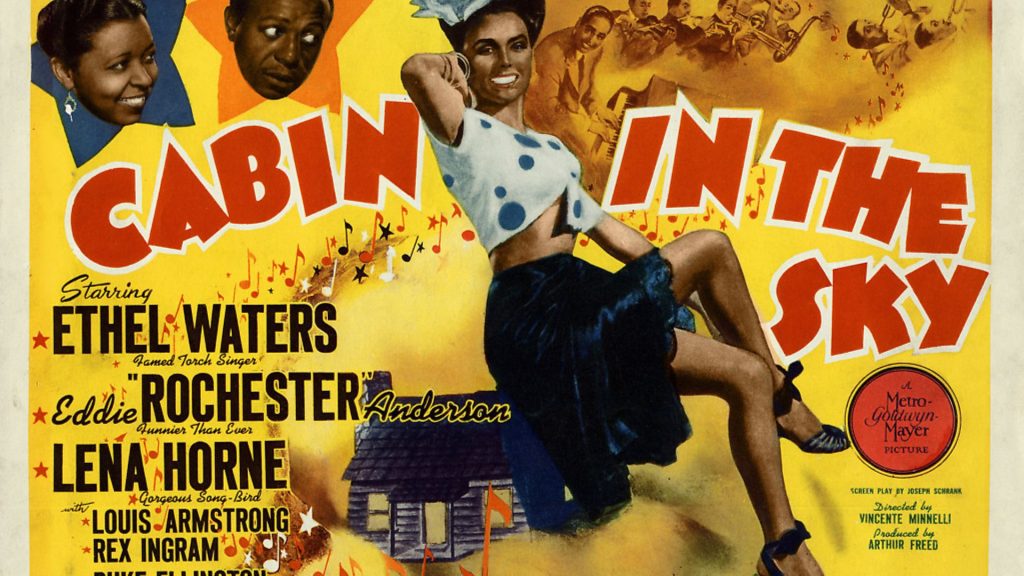

I found out how narrow my world was while contributing to a documentary about the great Hollywood director Vincente Minnelli, whose works included An American In Paris, Meet Me in St. Louis, Gigi and others. In the course of taking part in the documentary, I discovered his first film, Cabin in the Sky, which was released in 1943.

Cabin in the Sky was one of the most dangerous of films in those days: an all African American musical. It was dangerous because films with black actors and performers had trouble in the South. Racial segregation relegated African Americans to second-class citizenship. They were often confined to what was known as the ‘peanut gallery’ – the upper balcony of the cinema. Up there the view was not as good, it was crowded and did not receive the same customer service as the rest of the cinema. It felt like the cage it was.

Sometimes films with even one black cast member were not exhibited. Legend has it that Ella Fitzgerald was considered for the part of Sam, the singer/pianist in Casablanca, and Ella was ready for it. Bogart was on board, too, but Warner Brothers, the producers, were not. They decided that to have a black woman pianist at Rick’s implied too much: that maybe she and Rick were a thing. So that idea was DOA.

But Minnelli and MGM decided to release Cabin in the Sky, a great Broadway hit, with much of the original cast. And the result is glorious. But Ethel Waters – the star of the film – for me and my generation, was this little old lady who played maids and toured with Billy Graham. So I never wanted to see the movie.

In Pinky, which was released in 1949 and banned in a Texas town where the exhibitor’s defiance in showing it was upheld by the Supreme Court, Waters plays the saintly granny of a young, black woman passing for white. She was nominated for the Best Supporting Actress Oscar.

She then went on to play a maid in Member of the Wedding, and then had a television show, again about a come-to-the-rescue maid, Beulah. She left that because she found the portrayal degrading. In short, Ethel Waters was everything that my generation vowed not to be: We were Malcolm X not Mammy.

Yet what Minnelli gives us in Cabin in the Sky, in the guise of a rather trivial and stereotypical story of a gambler who is fatally shot and learns the error of his ways as his wife and the devil do battle over him, is the genius of Waters in full flower.

The child of a girl raped underage, Waters created herself. Not only was she a role model for black females and working class women; she was also an LGBTQ hero who never hid her sexuality. She escaped an abusive teenage marriage and, after singing at a party on her 17th birthday, she got a job at a theatre. At close to six feet tall, she became one of the faces of the Harlem Renaissance, that era in the 1920s when black people embodied modernity and the escape from the old order and the old world.

Waters was the Queen of Broadway in the 1930s, where Minnelli, the whizz-kid of the Great White Way, would have seen her. In Cabin in the Sky, he allows us to see her two sides: the pious, saintly, long-suffering wife praying for her husband, and the other side: the Queen Of Broadway, when she allows herself to show her husband what he’s missing.

She transforms herself into the Sweet Mama Stringbean – a stage name of hers – of the Harlem nightclubs: iridescent, alluring, honey-voiced. This is the person my generation never saw. And we judged her for it.

Cabin in the Sky also gives Lena Horne her only starring role. This great beauty, great singer and pin-up of my late father’s generation of Second World War black GIs, is framed as the glamour queen she is. The immortal Duke Ellington is there, too, in all of his elegance; Louis Armstrong has a moment, and the great actors, Mantan Moreland, Rex Ingram and the superb Butterfly McQueen feature, too.

Plus Minnelli borrows the tornado from The Wizard of Oz and throws in a stairway to heaven to add to the mix. It is a revelation. One, in the past, that I would never have discovered.

In this era when we all hasten to pigeonhole ourselves and to seek approval for doing so, it’s a kind of nobility to be blind-sided, to look through the lens of surprise. Because sometimes when we do, we leave the herd. And change.

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37