charlie connelly attempts to buck the current trend for cultural stalemates, by picking the best.. and worst of 2019’s literary offerings.

As politics grows ever more cutthroat, with grandmothers climbed over, ambition getting ever more naked and politicians competing with each other to tell the biggest straight-face whoppers ever uttered, matters cultural seem to be on an entirely different course on which everyone arrives first and all at the same time. In this era of voracious greed and ruthlessly rampant ambition our writers and artists seem destined – and sometimes determined – to share. No losers, only victors.

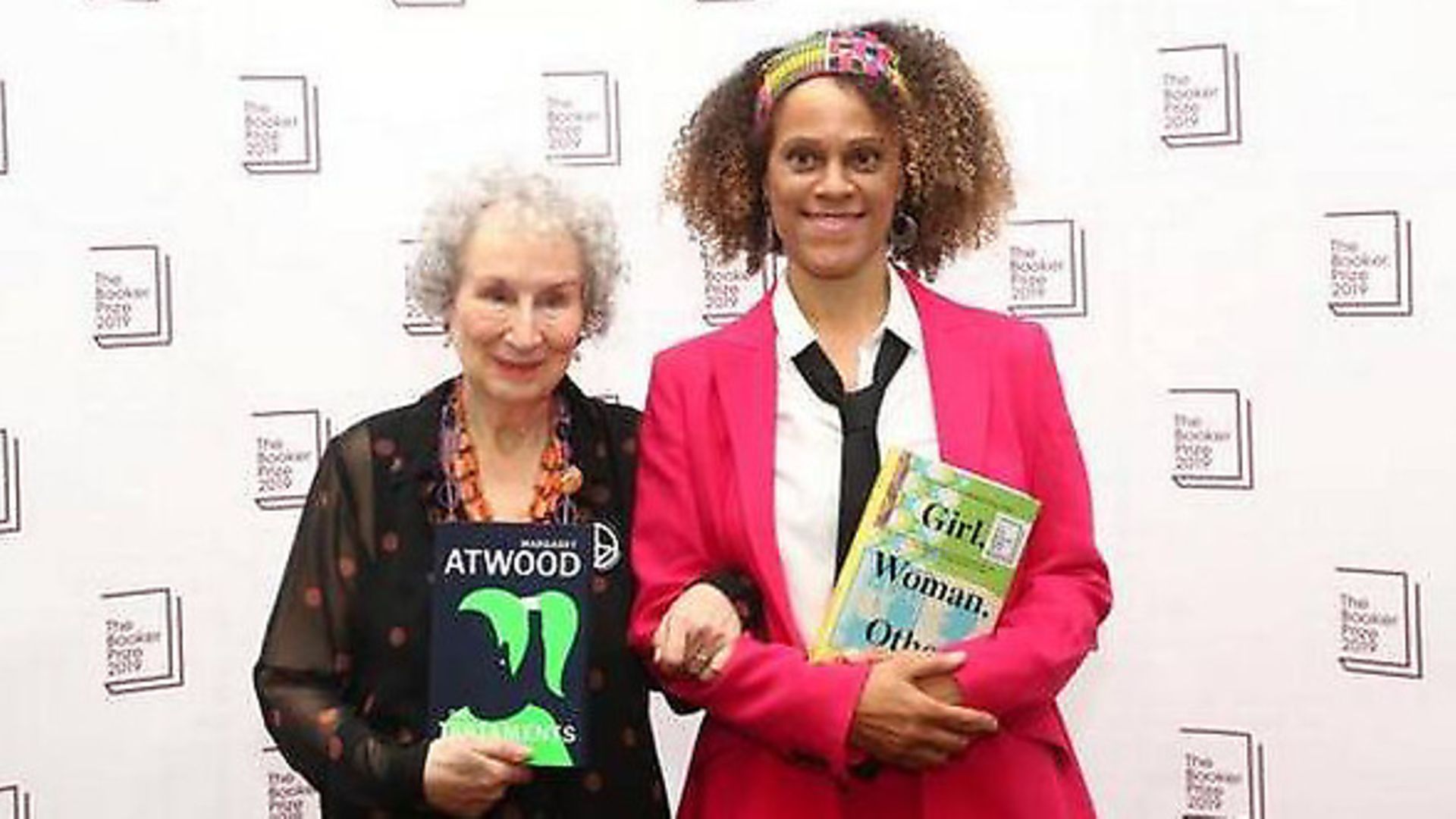

Earlier in the autumn, the Booker Prize judges startled everyone by announcing joint winners in Bernardine Evaristo and Margaret Atwood (and shame on BBC News for last week referring to the award going to Margaret Atwood and “another author”). There were also two Nobel literature laureates, albeit the prizes awarded to Olga Tokarczuk and Peter Handke were for different years, while the Bad Sex Award was shared by the saucy coupling of Didier Decoin and John Harvey. Then the Turner Prize went even further than their literary counterparts with all four shortlisted artists announced as the winners. Coincidence? Or are we on the cusp of an era of competitive non-competitiveness where the draw is the noblest outcome?

When everyone assigned with the specific task of picking a single winner starts being awfully, terribly, oh-no-I-couldn’t-possibly-choose pleasant to everyone else like this it sets us on a curious path. Where does it lead from here, longlists automatically becoming shortlists and, by extension, winners? If everyone’s going to start winning, imagine the size of awards ceremonies if they all turn up, posh frocks on with the expectant glint in the authorial eye that only a free meal can induce.

By the time the prize money is divvied up there’ll barely be enough to cover each trophy-brandisher’s dry cleaning, not to mention the need for everyone to give a speech: The thing could go on for days. Britain’s odd-shaped glass trophy industry would go into overdrive and could feasibly become the Brexit-busting economic bonanza to save us all from dystopia while engravers become the new 1%. I for one am about to start a business making little stickers that say “Prize Winner!” ready for affixing to every book cover printed from now on. Quids in, my friends. Quids. In.

Before I do, however, I intend to fly in the face of this newly-levelled playing field with no goalposts by rounding up some of the highlights of literary 2019 and blatantly and brazenly picking my favourites, one fiction, one non-fiction.

It’s not an easy task: I read very few bad books this year, which means either that we’re in some kind of golden era or I’ve become a benevolent, dozing softie in my old age. Indeed, the only book I can remember feeling genuinely snarky about was Jacob Rees-Mogg’s The Victorians, of which I read but one chapter, enough to tell me it was just a posh Wikipedia of the 19th century written in the style of a 1950s fifth former hoping his history essays might sway things to make him a prefect.

Ian McEwan’s Brexit-related novella The Cockroach was my biggest disappointment, a flat, one-joke satire so heavy-handed it’s a wonder he could lift them high enough to type, but otherwise I read some outstanding stuff.

Let’s start with Evaristo, whose Booker win for Girl, Woman, Other (Hamish Hamilton, £16.99) was thoroughly well deserved. It is a shame that the eruption of “goshes” and “good-graciouses” that greeted the split decision overshadowed this groundbreaking success for a black British woman who was treated as a bit of an arriviste in the aftermath of the announcement but has a long track record in adventurous, original fiction.

The warmth and humanity that shines through the dozen character narratives that make up Girl, Woman, Other provide a welcome relief from the news cycle and a sense that all is not lost. Hopefully her Booker success will lead people through her winning opus to explore the varied, fizzing septet of her backlist.

I read few more original novels this year than Sandra Newman’s The Heavens (Granta, £12.99), a magnificent combination of millennial Manhattan and Tudor England that shouldn’t have worked but absolutely did. Combining time travel, romance and tiptoeing along the line between soothsaying and delusion, Newman’s story of Kate, who has in her dreams occupied a land named Albion for as long as she can remember, and her relationship with Bangladeshi-American Ben, swings between the world of New York at the millennium and the courtly shenanigans of 16th century England, keeping the reader guessing as to whether Kate’s nocturnal excursions are in her mind or she really is regressing in time when she nods off. A beautiful novel and a wonderful achievement.

I also enjoyed The Rain Watchers by Tatiana de Rosnay (World Editions, £11.99), a moving family saga set in Paris against relentlessly rising flood tides swamping the city from its heart outwards, arrondissement by arrondissement. Published in March barely a month before the catastrophic fire at Notre Dame – the cathedral lurks on the cover, faint like a ghost – and at the height of the Extinction Rebellion protests that brought cities around the world to a standstill, this was about as timely as literary fiction gets. An elegant book by an elegant prose stylist.

Back in January I commenced with some trepidation a novel called The Capital by Robert Menasse (MacLehose Press, £15). Trepidation because this was a 400 page half-brick of a book concerned with the workings and machinations of the European Commission: Even the cover blurb, the zinging, snappy couple of paragraphs designed to convince you you’re holding a whizzbang, copper-bottomed winner with which you should hurry at once to the tills, began, “Brussels, a hive of tragic heroes, manipulative losers, involuntary accomplices. No wonder the European Commission is keen to improve its image”.

From these unpromising beginnings I found a sharply observed, witty novel, a character comedy with much to say about Europe today and the bureaucracy that runs it. Its satirical touch is far lighter than Ian McEwan’s and the book, translated from the original German by Jamie Bulloch, is the best novel about European bureaucracy you’ll read. That may sound a little like being the best breakdancer in the care home, but it’s a brave and funny book.

Brexit hasn’t produced the torrent of related fiction it might have done, at least not yet, and what has appeared has largely been written about the middle class by the middle class. A welcome, triumphant exception was Broken Ghost by Niall Griffiths (Jonathan Cape, £16.99), a heartrending, visceral portrait of the overlooked and forgotten people at the margins of our society who will suffer most after Brexit. It begins with what appears to be a miraculous vision on a Welsh mountainside outside Aberystwyth, the glowing figure of a woman suspended in the air seen by three people returning at dawn from a rave that alters the courses of their lives in ways that are soul-searchingly profound.

Broken Ghost is a bleak, uplifting, angry, magical, heartbreaking, heartwarming book in which people keep on trying to be the best they can be despite a world designed to provoke them otherwise. Griffiths’ brilliant novel is by some distance my fiction highlight of 2019.

With the real world increasingly feeling like some kind of warped fantasy it’s a challenging atmosphere for non-fiction writers to produce the goods. It’s been a good year for the music memoir, with well-received volumes appearing from Debbie Harry, Andrew Ridgeley and especially Elton John, whose Me (Macmillan, £25) was a rollick of a ride through a remarkable life told with a thrilling mix of candour and humour.

Tracey Thorn’s honest, raw and warm Another Planet (Canongate, £14.99) was devoted to life before she became a musician, plundering her teenage diaries to launch a meditation on growing up in Brookmans Park, Hertfordshire.

“I like to think I’m London,” she writes in a book that goes beyond life-writing into the history and philosophy of the suburbs, “but in fact, like many people, I have suburban bones.”

The suburbs emerge from Thorn’s memoir as a rootless place whose inhabitants are governed by the times of the last train from the city, satellites of a metropolis built to look like fake gentility but developing a character and psychogeography of their own. As do their residents.

Shirley Collins’ memoir All in the Downs (Strange Attractor, £16.99) won the Penderyn Prize for music writing and deservedly so, recounting her life spent largely in a Sussex that’s the antithesis of the suburbs, where history is long seeped into the earth. In a country more receptive to its own musical traditions folk singer Collins would be a household name; instead she was forced to take a number of regular jobs to support her children and for many years lost the ability to sing at all after the trauma of her marriage break-up. Fortunately she was able to return to music, lending All in the Downs an epiphanic ending to a memoir and one of the best evocations of England I have ever read.

The big event of the political publishing year was David Cameron’s For The Record (William Collins, £25), a long book in which the vacuum left by its total absence of self-awareness was so powerful it’s a wonder that opening a copy didn’t cause all the windows to blow in. Apparently the erstwhile PM’s original manuscript had 100,000 words cut to slim the book down to its still hefty 750 pages.

Talking of men unaccepting of their own shortcomings, Hallie Rubenhold’s Baillie-Gifford Prize-winning The Five (Doubleday, £16.99) upset quite a lot of them. This brilliant piece of social history writing restores the women murdered by Jack the Ripper – Mary Ann Nichols, Annie Chapman, Elizabeth Stride, Catherine Eddowes and Mary Jane Kelly – to historical figures in their own right rather than just names and corpses on slabs. The women have a splendid advocate in Rubenhold, whose detailed research and fresh approach have reduced ripperologists – yes, apparently it’s a thing, almost exclusively a middle-aged, white male thing – to a furious brand of territorial, spluttering rage. Which can only be celebrated.

As we descend into the darkness of winter, literally and figuratively, I’m drawn back to Christiane Ritter’s account of how in 1934, at the age of 36, she travelled from her Vienna home to Hamburg and boarded a steamer bound for the Arctic to join her husband Hermann in his remote cabin at the tip of a windblasted Svalbard promontory 250 mountainous miles from the nearest settlement. A Woman In The Polar Night (Pushkin Press, £9.99), republished in Jane Degras’ sensitive translation, is escapism at its best, transporting us to a remote and challenging environment and turning what begins as a fish-out-of-water memoir into something profound and immersive, something to give us hope in these challenging times.

There hasn’t been much to celebrate when it comes to Europe this year but Nicholas Jubber’s Epic Continent (John Murray, £20) provided a reminder of its diversity and what it is that binds the stories and cultures of Europe. Jubber, a Patrick Leigh Fermor for our times, made an exhaustive transcontinental journey from ancient Troy to Iceland using national and regional epic poems along the way as his guide. Europe is thrumming with these ancient stories and poems of heroism and romance and Jubber uses them intelligently, cementing a brilliant idea with a brilliant book.

As well as recounting his travels Jubber has much to say on Brexit and nationalism that is well worth hearing. On the misappropriation by the British right of the term ‘Anglo-Saxon’, he writes of how, “None of the politicians manipulating these terms were able to quote from the gems of Anglo-Saxon culture, nor to recognise the continental trading network to thrive. Nor were they aware of the telling irony that the most iconic work of Anglo-Saxon literature [Beowulf] is set in two nations still in the EU with a narrative that dramatises the importance of diplomatic alliances.”

Epic Continent is a valuable and timely reminder of what it is we’re fighting to stay a part of, expressed in some very fine writing indeed. It’s also my non-fiction pick of the year.

In a nod to the spirit of this new cultural niceness I won’t pick an overall winner. If there is to be one it’s up to Niall Griffiths and Nick Jubber to settle it between them, shirts off, in a pub car park.

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37