In this week’s Brexit Deconstructed, JAMES BALL discusses how chaotic governments can open the door to evil doings.

When staff start briefing against the world leader they work for, the results are rarely flattering.

Take briefings of one particular head of state, whose personal aides commented he would appear ‘shortly before lunch’, spending the morning reviewing the media. When he is out of town, the same aide notes, it gets ‘even worse’, with whole days lost to late starts, afternoon excursions and evenings spent watching movies.

‘I’ve sometimes secured decisions from him, even ones about important matters, without his ever asking to see the relevant files,’ one former chief press secretary complained.

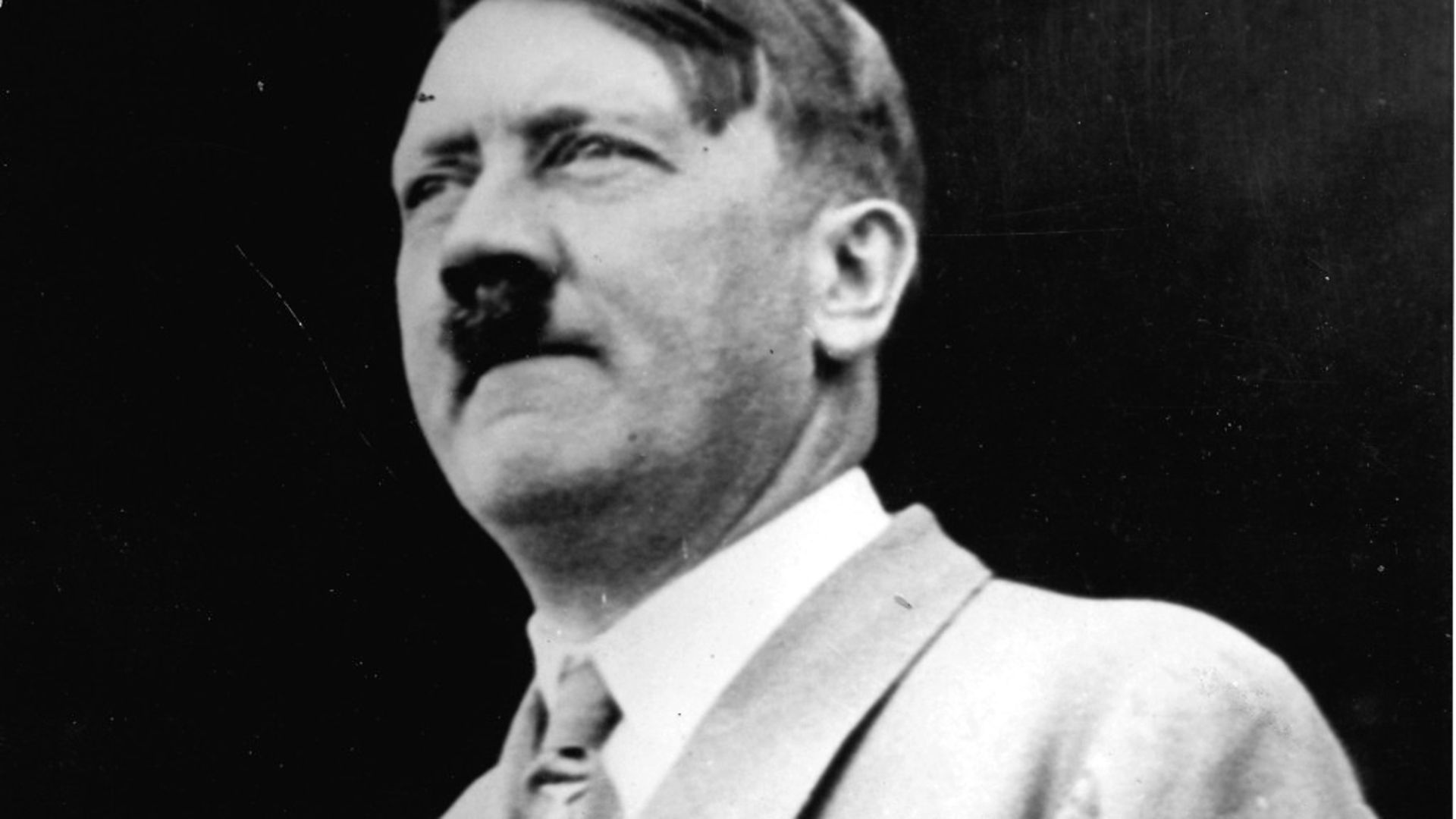

The remarks might sound familiar of a current world leader, but they’re historical – and the subject of them is Adolf Hitler, the architect of Nazi Germany and a man vilified as one history’s greatest monsters. ‘Lazy’ and ‘chaotic’ are not words which jump immediately to mind for most of us when we think about Hitler’s administration, but those who worked in it said those were two of the time’s defining traits.

‘In the twelve years of his rule of Germany, Hitler produced the biggest confusion in government that has ever existed in a civilised state,’ his chief press officer Otto Dietrich said in later testimony.

When we think of dark historical times, we don’t think of chaos and confusion from those who perpetrate them: we imagine evil acts resulting from detailed (if nefarious) planning and organisation. A chaotic or disorganised government comes to seem as less of a threat. A more detailed reading of history reveals it’s not.

This means we should not take comfort in seeming incompetence: while Hitler’s regime is history’s most extreme example, but in our present day chaotic governments and movements could still in time becoming hugely damaging ones.

The ingredients are present in countries across Europe: in Eastern Europe, populist right-wing governments in Poland, Hungary and Romania vilify immigrants, promote nationalism, and encourage globalist conspiracy theories about billionaires – often Jewish – meddling in democratic systems. One in three people who voted in the French presidential election backed the candidate from the National Front.

America has elected a nativist president who has in his first year fostered conspiracy theories against his own law enforcement and judiciary department; attempted to introduce a ban on Muslims travelling to the country; and called on multiple occasions for his political opponent to be locked up.

In Britain, we are navigating our own popular revolt, in the form of Brexit. The government is trying to implement perhaps the most complex political project the UK has attempted since the end of the Second World War, disentangling forty years of political union and forging a new trading relationship upon which the UK’s future will depend.

It is trying to do so with no political majority, no consensus among even cabinet ministers – let alone MPs – and with no guide to follow. Trickier still, it is doing it against a backlog of huge expectations: the people who voted for Brexit did so because they were unhappy with the status quo, unhappy with Britain’s current elite, and unhappy with the direction of travel.

These voters have been led to believe they can have better trade with Europe and the rest of the world, more control over laws and regulations, more money for the NHS, and less immigration than the UK used to have – with Theresa May promising time and again that this can be cut to ‘tens of thousands’ – a pledge not even her own cabinet believe or support.

The work in the aftermath of the Brexit vote has revealed that many of these pledges are impossible, or at the very least, mutually exclusive – but political rhetoric from many staunch Brexiteers denies these realities, instead saying on TV, in newspapers and across the internet that Brexit is being sabotaged, that naysayers are deliberately undermining the negotiations, that disagreement is undemocratic or even unpatriotic.

Where this becomes especially dangerous is when those on the mainstream right feed the nastiest fringes of those movements – as the Daily Telegraph, Daily Mail and The Sun did last week. Faced with the revelation that the Hungarian-American billionaire George Soros helped fund ‘Best for Britain’, a group trying to encourage the public to petition their MPs to reverse Brexit, the papers accused the Jewish billionaire of backing a ‘secret plot’ with his ‘tainted money’, even parroting Kremlin-backed accusations against Soros.

Brexit will be an arduous slog, a process involving thousands of pages of tedious details and painstaking compromises – less a bold march into a brighter future than months wading through a dismal swamp.

That the Cabinet still don’t know what kind of Brexit they want 11 months after signing Article 50 is a good sign of that complexity, and that the referendum question was nothing like a clear or settled one – if ministers don’t know what post-Brexit should look like, it is patent nonsense to claim the 17 million people who voted for leave had one identical vision.

Brexit is playing with dangerous political forces at a time when the world is unstable and nationalists and conspiracists are in the ascendant. For Brexiteers and their supporters to tap into those currents to try to get the deal they want is a dangerous and ugly game. Principled leavers need to call them out on it, and fast.

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37