The interwar heyday of Britain’s seaside resorts coincided with the height of the Art Deco style. As a new exhibition shows, this was a very happy coincidence. RICHARD HOLLEDGE reports.

A young woman perches on a diving board high above the swimmers in the lido below. She wears a bathing cap, a decorous swim suit and looks over her shoulder ever-so-slightly coquettishly.

She is the image chosen to publicise the exhibition Art Deco by the Sea at the Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts, Norwich – a picture of health and happiness which adorns the buses, the train station, hoardings and many a spare wall in the city.

There is more to the image than a jolly come hither look. The poster also highlights the sleek lines of the lido with its café and changing rooms, it speaks of a fun day out at the seaside for the masses – here in New Brighton and Wallasey – and advertises the fact that cheap rail fares can be bought from the LMS (London Midland Service) to whisk you to this nirvana.

It’s an image which captures a brief flowering of seaside sophistication in the years between the two world wars and which came to be expressed in distinctive Art Deco style – the curves and the contrasting straight lines of the new hotels, the sleek trains, the elegantly utilitarian furniture, the clothes and even the Bakelite radios the holidaymakers listened to in their fashionable new surrounds.

As exhibition curator Ghislaine Wood suggests in the catalogue, the seaside became a place on the margins where land met sea, where the pleasure principle was given more rein and the artists, designers and architects had greater freedom to express themselves.

Its increasing popularity also coincided with a time of social upheaval when the country was recovering from the First World War and increasing amounts of money were trickling into pockets of working families, especially with the passing of the Holidays with Pay Act in July 1938 which entitled everyone to one week’s paid break from their labours.

It is the publicity posters which capture the joie de vivre of the time. Influenced by the trailblazing Paris Exhibition of 1925 British designers realised the value of a forthright message instead of signs overloaded with information. In fact, there was a call for the establishment of a Ministry of Fine, Commercial and Applied Arts to encourage designers to paint something for the ‘poor man’s gallery’ as posters were sometimes dubbed.

The world they conjured up was a healthy, active, place, where families cavorted on the beach, young men and women flirted discreetly by the pool, beach balls were hurled and cocktails sipped. Cocktails! Who could have imagined the working class men and women of the time sipping a Whisky Sour or a John Collins Gin Fizz?

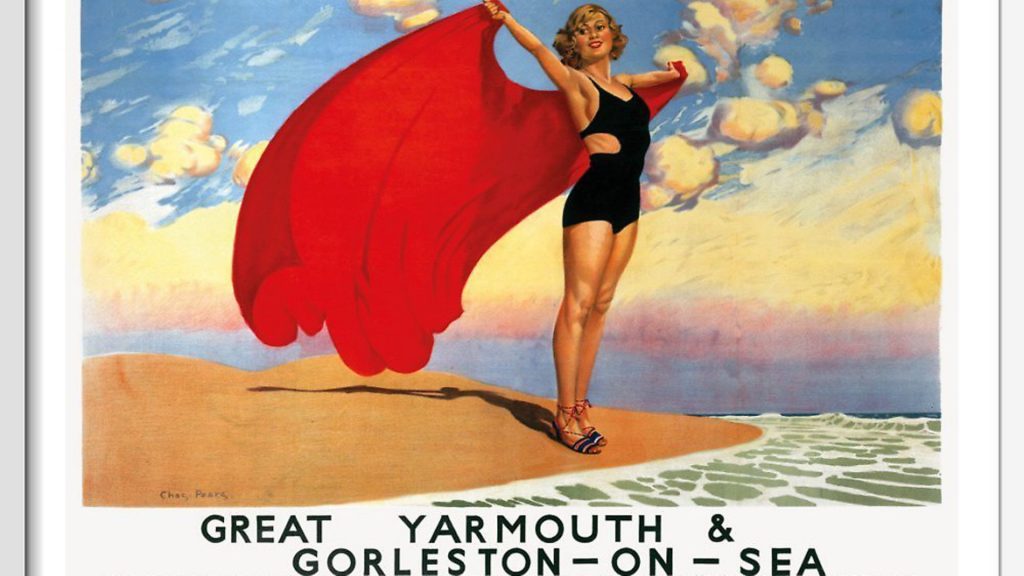

For example: it is hard to resist sheer exuberance of the sturdy blonde on the beach at Great Yarmouth by Charles Pears, arms outstretched, the wind tousling her hair; in Filey for the Family, by Reginald Higgins, a husband, wife and daughter, he with a nifty little moustache, she elegantly draped in a robe and holding a parasol, the child eager to play; in Southport, Fortunino Matania gives us just the merest hint of sexual frisson as a man helps a woman on with a robe, her swim suit slipping daringly down one shoulder.

by Fortunino Matania issued by London, Midland Scottish Railway. Picture: Victoria & Albert Museum – Credit: ©Victoria & Albert Museum, Lond

Perhaps the classiest series of images were by Tom Purvis who used primary, blocky, colours, to portray ramblers on a clifftop, children building sandcastles, fishermen, and a motor boat whooshing through the waves. The message is simple: “East Coast Joys, travel by LNER. To the drier side of Britain.”

Trains were essential to this seaside revolution. Not only did they employ many of the artists of the day to ensure their message was spread but they had become more efficient by being consolidated into four main lines, GWR (Great Western Railway), LMS, LNER and Southern Region.

Furthermore, the trains were streamlined beasts, using Art Deco graphics for their branding and aerodynamic wedge shapes to hurl the trains faster than ever. The Mallard still holds the record for a steam locomotive, which it set in 1938, travelling at 126 mph.

Inside the carriages, the Art Deco influence was just as marked with well- upholstered interiors – “All For Your comfort” declared one poster. Newly-designed buses and coaches, all curves and chrome, became popular and were cheaper but it was hard to beat the boast of the train companies: “It’s quicker by rail.”

As the crowds flocked to the coast, new hotels, cafes and bars sprang up with some of the country’s most memorable examples of Art Deco architecture. The Burgh Island Hotel, separated from the south Devon coast at high tide, is a confection of reinforced concrete designed by Matthew Dawson, all straight lines and a flat roof terrace on the outside with beams and columns making triangular shapes within. Central heating radiators were mounted vertically on the insides of the columns, running from the floor to ceiling where they were rounded off with sconces for the lights.

In the hallway, an alcove contained a banquette seat behind which a mural of the English Channel with impressions of the Mayflower, which would have sailed past carrying the pilgrims to America.

The artwork in the Midland Hotel, Morecambe, Lancashire, was altogether more ambitious. Works by the sculptor Eric Gill included a terrazzo floor – chips of marble, quartz, granite, glass – which reached the full height of the building and on the ceiling a medallion depicting Neptune and Triton surrounded by waves.

The tea room’s walls featured a mural by the artist Eric Ravilious of fireworks and seaside illuminations against a dark background which he described as celebrating “a seaside, gay with steel and white concrete buildings, a circular tower with a winding staircase and numerous diving boards”. The mural was ruined by damp and was painted over and the hotel itself fell into decline until 2008 when its 1930s charm, with its balconies and gently meandering lines, was revived.

In its heyday it appealed to the upwardly mobile and the less so but as the LMS controller of hotels remarked: “We must not confuse them with the class of people who will be using the hotel… We must walk with kings in the hotel but not lose the common touch in the bar”.

Similarly visionary was a 14-storey block of flats in St Leonards, Sussex, inspired by the Art Deco lines of the recently-launched Queen Mary, while along the coast in Bexhill, the De La Warr Pavilion, designed by two émigré architects, the German Erich Mendelsohn (1887-1953), and Serge Chermayeff (1900-1996) is a marvel of steel, cement and glass.

When it was completed in 1935 many locals regarded it as an alien intrusion but the interior with its two spiral stairs and huge bay windows is today reckoned a triumph.

Much of that flair was harnessed by the entrepreneur Billy Butlin with his first holiday camp in Skegness on the Lincolnshire coast which opened in 1936. Aimed at the cheap and cheerful end of the market, a neon sign proclaimed: “Our True Intent Is All for Your Delight” and he provided it with individual chalets, an outdoor heated pool and modernistic, flat-roofed dining, lounge and billiard rooms. He added a touch of glamour with the American Cocktail Bar which, with its sweeping counter and chromed tubular-steel seats, evoked the glamour of an ocean liner or the movie image of a New York hotel.

Essential to these resorts was the lido. In Penzance, sun lovers flocked to a triangular pool set between rocks and wavy concrete walls while in Brighton the Saltdean Lido included a library.

The New Brighton Lido, where our flirty girl was balanced on the diving board, was the biggest of them all with space for 12,000 visitors, sheltered within reinforced concrete walls and plenty of room on its terraces for sunbathing.

What also pulled in the crowds were the amusement arcades where they could enjoy the dodgem rides, thrill to the daredevil motorbike riders whirling around a vertiginous Wall of Death, and lark on fairground rides. No longer were the arcades decorated in the Baroque style of the 19th century, now they looked sharp and modern. As one admiring contemporary critic declared: “Lighting effects at night flashed and sparkled with a brilliance that truly created a Boulevard of Beauty and Delight.”

When it came to arcades, Blackpool led the way, spending more on leisure than any other resort with £1,500,000 invested in seven miles of promenade extensions, £300,000 on indoor baths and a pool which cost £75,000.

The Pleasure Beach attracted the trippers with its Fun House, the wooden rollercoaster of the Grand National, a maze, as well as a range of treats such as an ice cream soda fountain, and above all, an Art Deco masterpiece, the Casino.

Designed by Joseph Emberton (1889-1956), the building was centred on a large concrete drum, a 92-foot tower and dramatic outdoor spiral staircase. It boasted a grill room, an American-style soda bar, the country’s biggest fish-and-chip diner and, to appeal to a wealthier market, a stylish à la carte restaurant with air conditioning and automatic doors.

Lord De La Warr, owner of the pavilion that bore his name, had spoken for all at the opening in 1935 when he talked of “a new industry” which gave “that relaxation, that pleasure, that culture which hitherto the gloom and dreariness of British resorts have driven our fellow countrymen to seek in foreign lands”.

How could he have foretold that the “new industry” was to flourish only for that brief period between the wars when the demand, the means and the style, all came together in such a singular way.

What irony that by the 1970s those foreign lands were more appealing than ever for holidaymakers in search of the sun and that many of the fine buildings and grand resorts would have slipped into decline.

Art Deco by the Sea runs at the Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts, Norwich, until June 14

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37