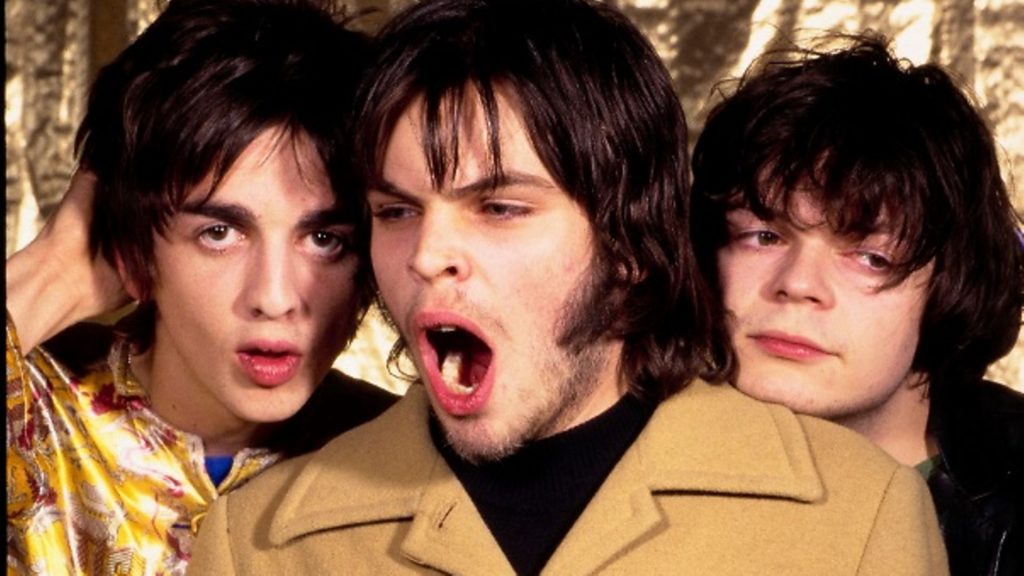

Music photographer KEVIN CUMMINS took many of Britpop’s era-defining images and knew all its key players. So, as his new book about the period is published, why does he feel conflicted about the musical movement that sparked Blur v Oasis and Cool Britannia?

In the mid-1990s anything and everything British was cool. Celebrity mockney chefs: cool. Lads’ mags: cool. Tony Blair: cool. The Spice Girls: cool. Ladettes: cool. New Labour: cool. Britannia: cool.

Except none of it was cool.

Britpop was a term I was uncomfortable with, and I wasn’t alone. In April 1993 Select magazine dropped a photo of Brett Anderson over a backdrop of a Union flag, using the coverline: “Yanks Go Home! Suede, St Etienne, Denim, Pulp, The Auteurs and the Battle for Britain”. They were reducing the standard of the once-lofty music press to the level of red-top, flag-waving patriotism.

Suede’s Brett Anderson was furious. His songs were documenting the world around him, illustrating its cheapness and failure, not about Britishness in all its perceived glory.

Twenty-seven years on, he joins me and several of his peers in feeling conflicted about how the era’s breezy confidence became tainted by nationalistic exceptionalism.

“The use of the flag is interesting,” he says in my new book While We Were Getting High: Britpop & the ’90s. “It’s fascinating how something that loaded can be interpreted completely differently depending on the context.

“Look at how Morrissey’s use of it at that Finsbury Park gig in 1992 was seen as nationalistic, whereas Geri Halliwell’s and Noel Gallagher’s use later in the decade was viewed as patriotic.

“It’s an indication of the blithe optimism of Cool Britannia that people managed to get away with waving flags. It’s an indication of how different the political climate is today that exactly the same act would now be viewed as deeply troubling.”

Despite Brett’s reservations, Britpop became a movement and flag-waving became the norm. Most British bands distanced themselves from the term, but they were fighting a losing battle.

For a period of three or four years, UK bands would be asked repeatedly about their Britishness. They weren’t asked about the elements of toxic masculinity, misogyny and racism that many commentators – and musicians – were uncomfortable with.

Brett told me he now views Britpop’s “core politics as anachronistically patriarchal and, actually, borderline toxic”, and another interviewee for my book, Gene’s Martin Rossiter, pointed out: “If you look at all the NME front covers for 1995, only 10 featured women and only two included people of colour… I’m slightly ashamed that at the time I didn’t see it for what it was – a return to a white, male-dominated Britain.

“The responsibility lies mainly at the doors of the music and media industries, but I certainly didn’t hear the artistes at the time speaking out and I have to include myself in that list. Some maybe did, but it wasn’t a narrative that was part of the zeitgeist.”

Sonya Madan of Echobelly prefers to remember the “exuberance and joy that Britpop championed.” She told me: “The seeping-in of shame when it comes to nationalist pride is a modern-day obsession. If it’s done with a positive appreciation for one’s culture, why shouldn’t it be exuberant? To feel obliged to denigrate a musical scene because of the politics of the current climate means you limit your appreciation of all the good things it had to offer.”

A quarter of a century on, however, the symbolism of the Union flag is more loaded and exclusivist than ever and I find it hard to separate Britpop from today’s political climate.

Was it really a precursor to the Brexit mentality? It’s hard to truly know, though I suspect a connection somewhere along the way.

At NME, where I photographed Blur, Oasis, Suede and the key bands of the movement, I like to think we distanced ourselves from the more laddish end of the spectrum. We concentrated on the musicians and their music, and some great music came out of this period.

“Looking back on it now,” Noel Gallagher told me, “I think Charles Dickens might well have summed it up best in 1859 when he wrote: ‘It was the best of times, it was the worst of times’.

“Has it (Britpop) aged well? Yes and no. The attitude of the main players was correct and even some of the music still stands up, but sadly the cartoonish element of it has been allowed to survive.”

- While We Were Getting High: Britpop & the ’90s by Kevin Cummins is published by Cassell Illustrated.

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37