A new exhibition at the Barbican reveals how clubs allowed new artistic ideas to flourish free from conventional constraints.

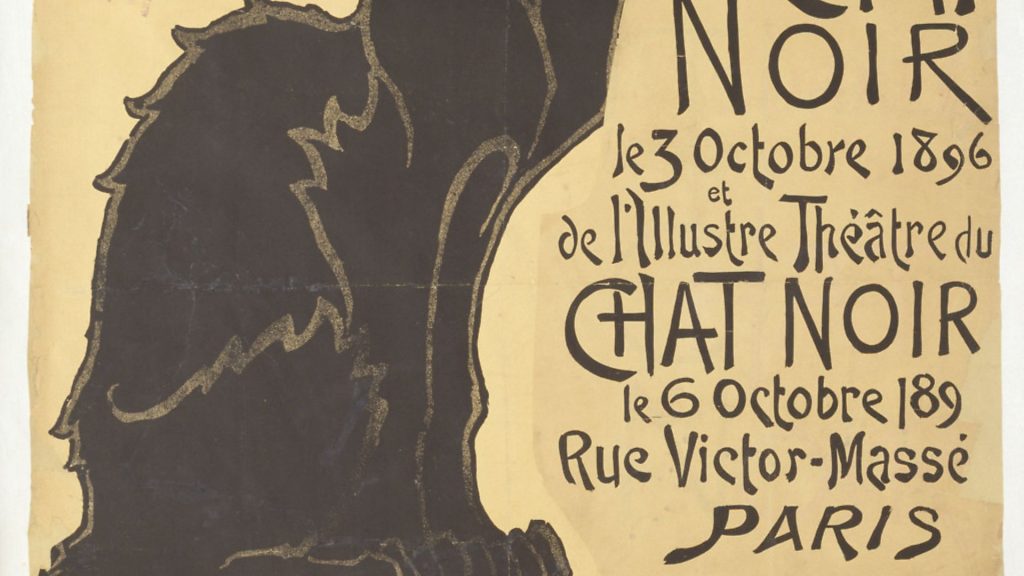

“Be modern” enjoined the sign over the entrance to the Chat Noir, the night club immortalised in its much parodied and reproduced poster, and an emblem of Parisian artistic and intellectual life in the Belle Époque.

Café culture had been at the heart of bohemian identity ever since the impressionists began gathering in the bars and cafes of Montmartre in the 1870s. By the early 20th century, ‘artistic cabarets’ – intimate spaces that provided artists with both a meeting place and a platform – were springing up in cities across Europe.

An exhibition at the Barbican art gallery celebrates these night clubs as the beating heart of the avant-garde, crucibles of modernity and artistic experimentation in Europe and beyond from the 1880s to the 1960s.

Unconstrained by traditional boundaries, the Chat Noir played host to every art form. Satire squarely aimed at the bourgeoisie, readings of experimental poetry, and absurdist plays, such as Alfred Jarry’s Ubu Roi, 1896, in which actors took the role of puppets, took place in its dark and elaborately decorated interior, the walls hung with Japanese masks, antiques and pictures. It quickly became famous for its shadow theatres, which developed from a traditional form of family entertainment to something far more sophisticated, involving fabulous visual effects and integrating music and movement. Music was essential to the club’s atmosphere, and Erik Satie was employed there as a pianist from 1887 to 1891, his fellow composer Claude Debussy a regular customer.

The club attracted many of the most significant painters of the day, including Paul Gauguin, Pierre Bonnard and Edouard Vuillard. Henri Toulouse-Lautrec would become synonymous with Montmartre’s nightlife, and his poster designs capture its spirit in both content and medium.

A letter to his mother from 1886 highlights the transgressive nature of the club scene, and he writes: “I’d like to tell you a little bit about what I’m doing, but it’s so special, so ‘outside the law’.”

Artists’ clubs were, to varying degrees microcosms, in which the rules and conventions governing society at large could be contradicted, suspended or relaxed. For female artists – specifically performers – they provided a rare platform and some of the most prominent female figures of the avant-garde of the early 20th century were dancers.

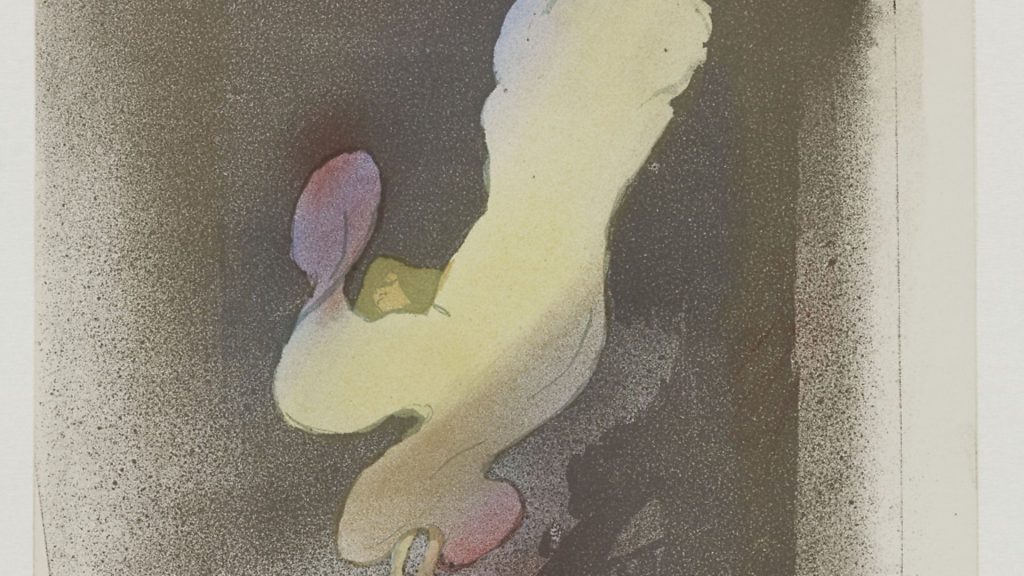

The Chat Noir was not a particularly nurturing environment for women artists, but the club’s radical offerings had a direct impact on the American dancer Loïe Fuller, whose experimental performances seem to have been heavily influenced by its shadow theatre.

Fuller made her Paris debut at the Folies-Bergère, and a series of lithographs made by Toulouse-Lautrec in 1893 gives a vivid sense of her pioneering act. Billowing swathes of fabric and complex lighting effects resulted in complete abstraction, the effect less of a person dancing and more of a shifting, plasma-like mass.

Female performers made a significant contribution to the Cabaret Fledermaus, which opened in Vienna in 1907, as a realisation of the concept of the Gesamtkunstwerk (total work of art) proposed by the composer and theatre director Richard Wagner. The club was founded by the Wiener Werkstatte (Vienna Workshop), a group of artists and designers which, inspired by William Morris’s Arts and Crafts Movement in Britain, prized individual worksmanship over mass production.

In contrast to the elaborate, faux-medieval interior of the Chat Noir, its bar was decorated in brightly-coloured tiles inspired by Austrian folk art. Some idea of its appearance can be gained from two postcards created by its designer, a co-founder of the Wiener Werkstatte, architect Josef Hoffman.

Probably named after Strauss’s 1874 opera, Cabaret Fledermaus was designed down to the smallest details, with cutlery and waiters’ pins as crucial to the overall effect as the auditorium. Performances would place equal emphasis on script, music, costumes and sets, and a text setting out the purpose of the cabaret emphasised its conception as a total experience: “Here all the senses should be simultaneously at least animated, and if possible also satisfied, and no art with its proper means is excluded from contributing to the overall effect.”

By 1913, the Cabaret Fledermaus was closed, but it was by no means the last artists’ club to aspire to being a total work of art. L’Aubette opened in Strasbourg in 1928 as a multi-purpose complex including restaurants, cafés, dancing and cinemas. It was designed for the most part by the artist Theo van Doesburg, who, with the painter Piet Mondrian, was a founder member of the Dutch art movement De Stijl. Like the Wiener Werkstatte, De Stijl sought to remove the barriers that separated different art forms, and to dissolve the hierarchies that elevated painting and sculpture over design. Key to De Stijl’s integration of the art forms was its commitment to abstraction, and Van Doesburg’s ideas about the correspondence between colour, music and space were perhaps most comprehensively expressed in L’Aubette’s Ciné-Dancing, which combined dancehall, restaurant and cinema in a single space.

If L’Aubette stood for order, the Cabaret Voltaire was a monument to chaos. It was the product of deep crisis, a cri de coeur in the face of the First World War, issued from a room attached to a Zurich bar-restaurant. Its opening on February 5, 1916, marked the beginning of dada, an art movement that was both a refuge and a response to the war, which raged at its fiercest during the brief but eventful lifespan of the Cabaret Voltaire.

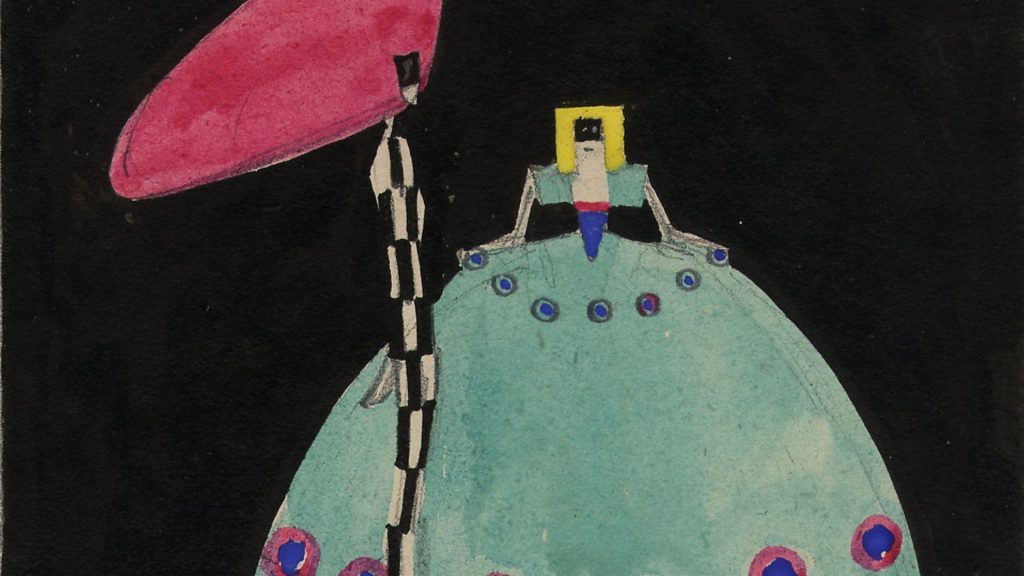

In a world turned on its head by conflict, rules, norms and conventions seemed suddenly meaningless, and the nonsense world of dada confronted madness with madness. Founded by Emmy Hennings and Hugo Ball, two artists who had fled Germany for neutral Switzerland, the Cabaret Voltaire staged bizarre, anarchic performances such as Ball’s famous Magical Bishop speech, which he delivered wearing a handmade cardboard costume, in a language that replaced words with sounds.

Though dada can be crudely characterised as nonsense, it was not self-contained and like most artists’ clubs, it embraced as wide a set of influences as possible, staging music, art, poetry and theatre in what Ball described as “a race with the expectations of the audience”.

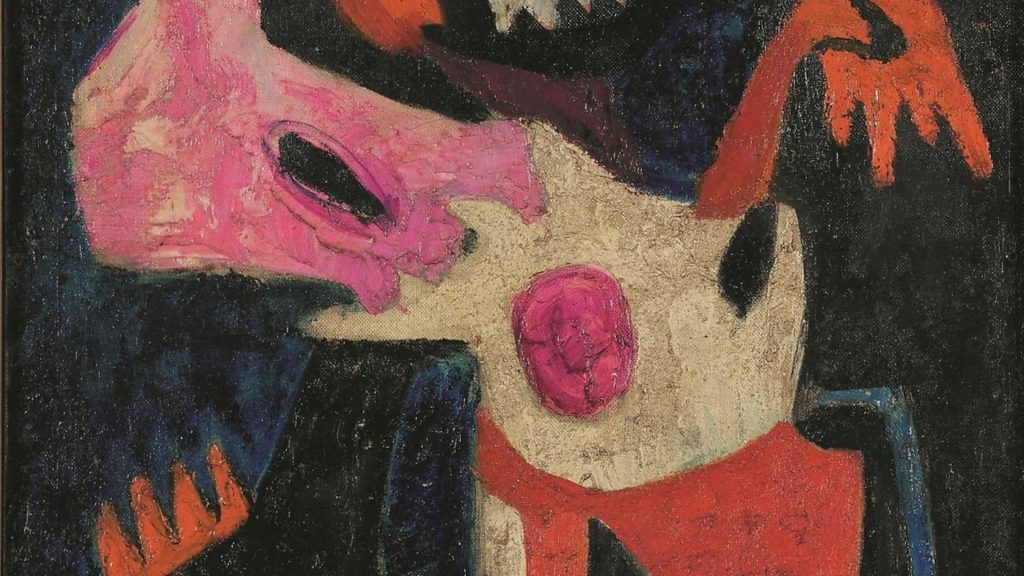

No club so completely encapsulated a total political and artistic philosophy as the Bal Tic Tac in Rome, designed in 1921 by the Futurist artist Giacomo Balla. Futurism had been founded in 1909 by Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, and though its glorification of war and destruction hampered its appeal after the First World War, it remained a potent force in the 1920s, celebrating the spirit and dynamism of the modern, industrialised world. When Marinetti opened the Bal Tic-Tac, it was as a total realisation of futurist aesthetics, with jazz bands providing a soundworld for a space animated with fragmented shapes, ‘speed-lines’, and ‘noise-lines’.

Balla’s colleague, Fortunato Depero was tasked with the realisation of another, possibly even more immersive world when he was commissioned to design the Cabaret del Diavolo, also in Rome. The cabaret took its theme from Dante’s Divine Comedy, and its three floors, Inferno, Purgatorio and Paradiso served as stage sets in which the audience became participants in a large-scale, immersive performance.

Escapism was an important element for many clubs in the early 20th century, and the Cave of the Golden Calf in London, its walls decorated with murals, provided a subterranean refuge for the city’s intellectual elite in the years immediately prior to the First World War.

The jazz clubs of Harlem provided a focus for the thousands of displaced African Americans who left the South to escape persecution and poverty after the First World War. But though the Harlem Renaissance nurtured and celebrated black culture in the form of blues and jazz, if anything it amplified the racist hypocrisy of the time, with many clubs admitting a white only audience.

The depiction of night clubs in Weimar Germany by artists such as Otto Dix and Jeanne Mammen describes them as places of desperate retreat, that perhaps only emphasised the sense of alienation that afflicted a population crushed by reparations, unemployment and the scars of war. Nevertheless, these crowded, claustrophobic scenes can be ambiguous, depicting the clubs and cabarets of Berlin as places of sanctuary, where LGBTQ customers and artists could be free from the fear of persecution. Women, too, are notably present in depictions of Berlin nightlife: They won the right to vote in 1919, and are frequently shown in bars and clubs alone or in groups without men.

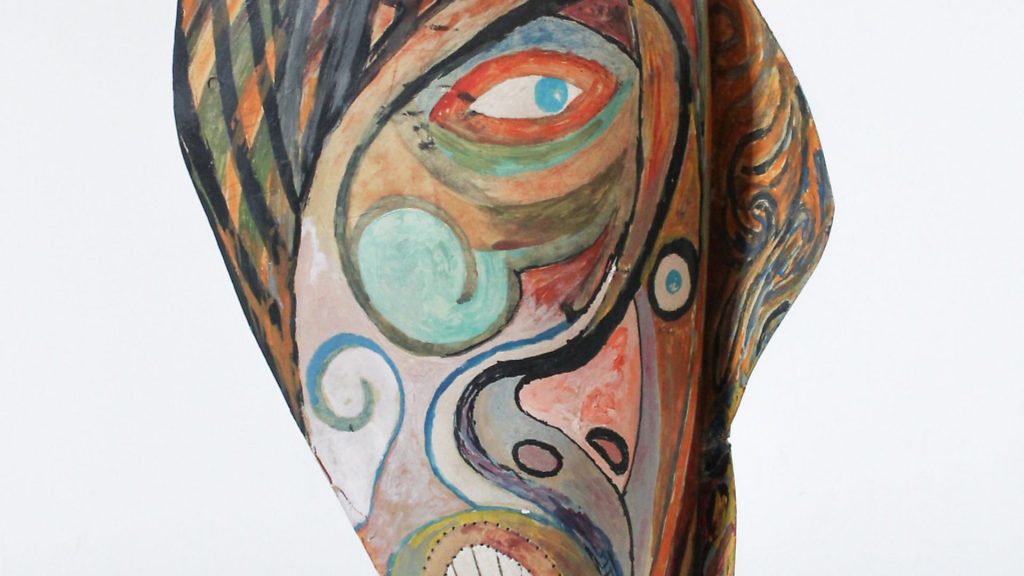

The Mbari clubs founded in Ibadan and Osogbo were an important force for the exploration and celebration of national identity after Nigeria gained independence from Britain in 1960. Founded in 1961, the Mbari Artists and Writers Club was named after traditional mbari houses, exuberantly decorated places of worship, with central courtyards that provided a natural place to congregate. The clubs provided a platform for Nigerian artists, and along with the Mbari publishing programme have proved a vital force in nurturing and reflecting African writing and art.

By embracing both the avant-garde and the traditional, the Mbari clubs were in some ways typical of artists’ clubs generally. Even the radically modern shadow theatres that began at the Chat Noir and spread around Europe had their roots in traditional entertainments like puppet theatres. But by providing artists with places to meet, experiment, and act freely, temporarily exempt from the rules of society at large, artistic-cabarets and night clubs allowed new ideas to flourish free from the constraints of the old and the conventional.

– ‘Into the Night: Cabarets and Clubs in Modern Art’ runs at the Barbican art gallery until January 19, 2020

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37