CHARLIE CONNELLY on a book which perfectly captures the allure of the remote

One of my favourite radio stations is called Arctic Outpost Radio and broadcasts from Longyearbyen, the main town on the remote Svalbard archipelago roughly halfway between the northern tip of Norway and the North Pole. It plays mainly vintage jazz and old crooners with no adverts; the only interruptions are station idents and the occasional emergency warning of polar bear sightings.

I like to picture Arctic Outpost Radio as coming from a small, remote hut, in which a bearded man with Bakelite headphones over his ears places old 78s onto the turntable of a wind-up gramophone, standing up every now and then to poke at an old stove and close a door that blows open regularly admitting a flurry of snowflakes, all the while wondering if anyone out there in the polar night is listening.

In reality Longyearbyen is a modern conurbation of around 3,000 people with a hotel, a cinema and even a kebab van. The radio station is doubtless a hi-tech operation broadcasting through a lightning-fast broadband connection allowing me to listen at home in crystal clear streaming quality rather coming through faintly among swirling static.

While I’m reassured to know there are almost 2,000 long, watery miles between me and those polar bears, the fact I can pick up Svalbard radio as easily as I can BBC Radio 5 Live demonstrates how small the world has been made by advances in communication technology. Many of us feel jittery if our phone is out of arm’s reach, let alone venturing out to the wilderness with only our wits to rely on. Genuine remoteness is hard to find in the world today.

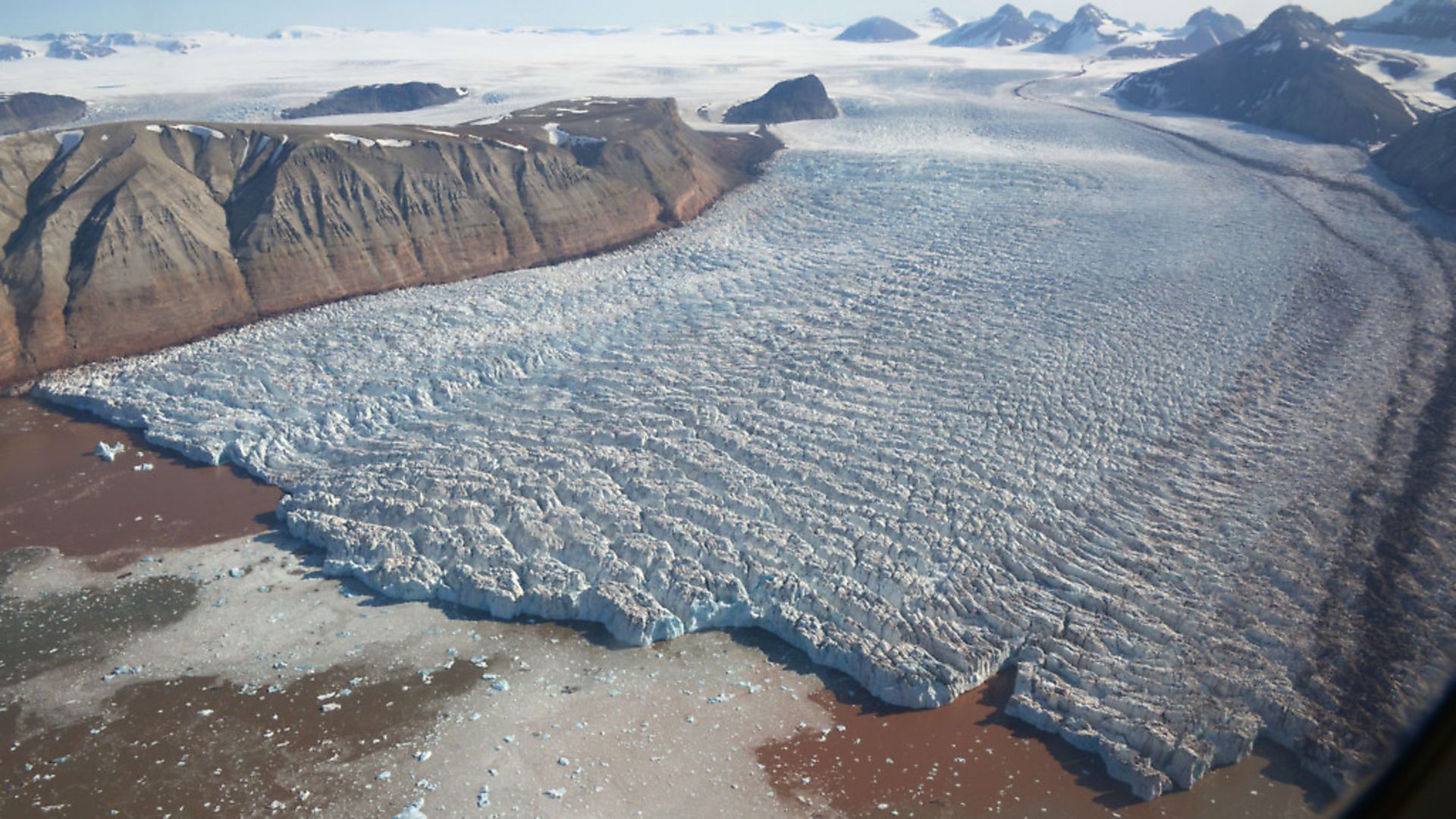

Svalbard was always one of the world’s wildernesses. Its development in a modern sense began when Dutch whaling expeditions began using it as a base in the 17th century.

As one of the last land masses before the North Pole it then became a jumping off point for Arctic explorers and during the 20th century the Soviet Union established mining operations there. It was a hard life for anyone spending a significant amount of time on the archipelago, forced to subsist on what seals, arctic foxes, eider ducks and, occasionally, bears they could catch and kill, not to mention coping with the constant darkness that fell between October and February.

The hardest lives were those of the hunters who would venture out to the harshest outposts of the Arctic wilderness, living in tiny huts on the fringes of the archipelago for months at a time. It took a certain type of physical toughness and a particular mentality to build a life on the edge of the world.

The last person you’d have expected to find out there among the seals, blizzards, bears and ice storms was a woman hailing from privileged, upper-class European society used to a world of servants and balls where every possible convenience was effortlessly available.

That’s exactly what Christiane Ritter was in 1934 when, at the age of 36, she travelled from her Vienna home to Hamburg and boarded a steamer bound for the Arctic to join her husband Hermann in his remote cabin at the tip of a windblasted Svalbard promontory 250 mountainous miles from the nearest settlement. She was forsaking the swanky café society of Vienna’s Ringstrasse for a year in Europe’s harshest and most unforgiving environment.

If the circumstances are a little baffling – Hermann had first travelled to Svalbard as part of a scientific expedition a few years earlier and stayed on, not to mention the fact the couple apparently had a young daughter at home – Ritter’s account of her time as one of the northernmost people in the world is a spectacular piece of writing. Published in German in 1938 and republished in English translation later this month for the first time in 50 years, A Woman In The Polar Night is as vivid and understated an account of life in the harshest conditions endured as you’ll find. It also turns that hardscrabble polar environment into one of the most beautiful landscapes in the world.

Her motives for joining Hermann are never overtly stated, but with his being absent in the north apparently for some years it might just have been the only way she was going to see her husband anytime soon. His letters were persuasive despite their less than enticing descriptions of how Christiane wouldn’t be lonely because their neighbour, an “old Swede”, was “only 60 miles away”. Having endured a long voyage and kitted herself out at Tromso in northern Norway with the assistance of a man who went to the South Pole with Amundsen, she arrives at the evocatively named Grey Hook with minimal luggage and a year’s supply of toothpaste.

Her first impressions aren’t great; the Arctic is just “freezing and forsaken solitude” and of their tiny hut she concludes: “Here we can live, we can also die just as it pleases us; nobody can stop us.” She doesn’t say as much but her mood was probably not exactly enhanced by the news she would be sharing the cramped cabin, with its smoky, temperamental old stove, not just with her husband but also with a Norwegian named Karl.

Having arrived from a bustling central European capital she finds it hard to adjust to the slower pace of life, not to mention the complete lack of daily routines. The sun never sets during her first weeks and all sense of routine is abandoned: They eat when they are hungry and sleep when they’re tired.

“Here there are no days because there are no nights,” she realises.

She also finds her husband changed – calmer, unflappable, serene even – something she finds challenging at first in both him and Karl, declaring herself “revolted by their equanimity”, but these are temporary frustrations. Soon Christiane finds herself succumbing to the magic of polar life. Not only that, she thrives in it.

Taught to shoot in case she ever finds herself confronted by a polar bear, she hits a tin can at 50 paces with one of her first shots. The first time the men kill a seal she returns to the cabin with its flippers in a bucket wondering if she’s supposed to bake, boil or roast them, but soon becomes a deft chef whenever fresh meat appears, despite a paucity of ingredients and rudimentary facilities.

It’s when she begins to shed her conventional thinking and accepts that she is in a place where humans can’t impose themselves on the landscape that the narrative really begins to fly. Her companions never worry and are quick to laugh, remaining cheerful even in extreme weather conditions when food is running low. Fatalism, Christiane realises, means downfall in the Arctic.

“Does one know here more clearly than elsewhere that everything goes in its prescribed way, even without men’s intervention?” she asks.

In Christiane’s submission to the elements and her surroundings A Woman In The Polar Night transcends from a fish-out-of-water memoir into something far deeper and more meaningful. The Arctic has inspired some great literature from writers as diverse as Barry Lopez and Tim Moore, but Christiane Ritter’s descriptive powers, honesty and increasing self-knowledge are shaped by a writing style that remains concise and contained to produce an extraordinary book full of sagacious insight into a world that’s not only long gone now but was far removed from convention even at the time.

“The lives of these hunters are a series of performances that are almost inhuman,” she writes, after the trio receive a visit from a passing trapper. “But they speak only seldom of their experiences. They are not out for fame, these men. They live far from the tumult of the world. Practically none of them has a home or a family. It is an unbounded love that chains them to the country. They are intoxicated by the vital breath of untamed nature through which the deity speaks to them.”

Everything about the polar landscape, the light, the geology, the weather, the animal life, is like nothing else at lower latitudes and Ritter restrains herself admirably from over-egged description, aware that what she witnesses is all but impossible to capture definitively in words even though she yearns for people to share it with her, to venture north themselves and see what she sees and feel what she feels.

“They have no idea that under this radiant heaven,” she writes in response to the northern lights, “a man’s spirit is also calm, clear and radiant.”

She survives the long, dark winter – all 132 days without sunshine – unscathed despite being left alone, sometimes for weeks at a time, when the men are away on hunting trips. A sure sign that she has immersed herself in the Arctic world is that not once does she complain. If anything she flourishes in hardship – Karl would later tell a friend that while he’d expected her to “go crazy” within weeks she was actually “a hell of a woman” – expressing nothing more negative than cocking the occasional snook at the weather.

When the sun returns and the men can see the pack ice is so thick the lack of open water means no bears or seals, their only prospect of fresh meat, Christiane writes, “it is becoming more and more urgent to get fresh meat”. It is the closest she ever comes to expressing genuine concern despite the thin line they constantly walk between life and death.

This is a deeply affecting book, a memoir so erudite and so wise it’s a mystery why it’s been out of print in English for half a century. The world is different today with everything available at the touch of a button. If you go online now within a couple of clicks of the Google homepage you’ll find a 360 degree movable panorama of the inside of the Ritter hut, which still stands. That, and the fact I can listen to Al Bowlly crooning My Blue Heaven from Longyearbyen as clearly as if it was playing in the next room, is what makes this wonderful book so special: The fulfilling of a desire for the otherworldly and immersion in nature and the landscape, the harsher the better.

“We are seized by an uncontrollable longing for remote places,” she writes as she and Hermann are picked up by a ship at the end of her year.

“We want to go further into the Arctic lands, the islands in the ice, the frozen earth, which is still lying there as on the day God created it. Europe, and everything that binds us to Europe, is forgotten. We have a wild longing, more urgent than ever before, and stronger than all reason and all memory.”

A Woman In The Polar Night by Christiane Ritter, translated by Jane Degras, is published on November 21 by Pushkin Press, price £9.99

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37