CHARLIE CONNELLY on pair of new releases, their contrasting receptions and authors, and what they tell us about Britain today.

It’s not often I enjoy seeing an author getting an absolute savaging from reviewers but the way the literary pages have gone after Jacob Rees-Mogg’s The Victorians: Twelve Titans Who Forged Britain (W.H. Allen, £20) since its publication at the end of last month has, I must confess, rather draped a rainbow around my shoulders.

Not only because Rees-Mogg is one of the more fanatical proponents of the seismic act of colossal national self-harm that inspired the launch of this newspaper, though that’s reason enough, but the literary evisceration of his preposterous book comes at a time of growing evidence of a distinct and much-needed cultural shift in publishing.

The Victorians is the Honourable Member for North East Somerset’s collection of 12 potted biographies praising notable figures from the late 19th century, all of them men except the eponymous queen herself, and not a single scientist, poet, author or artist among them. (Even Lytton Strachey, whose iconoclastic 1918 Eminent Victorians inspired Rees-Mogg to write this defensive response just 101 years later, managed to find room for Florence Nightingale.)

It hasn’t exactly gone over big with the critics. In the Daily Telegraph, Simon Heffer labelled it “a complete turkey”, parts of which “appear to have been written by a baboon”. For the cultural historian Dominic Sandbrook, in the Sunday Times, the book is “absolutely abysmal”, an opinion he has reached with regret.

“No doubt every sanctimonious academic in the country has already decided that Rees-Mogg’s book has to be dreadful so it would have been fun to disappoint them,” he writes. “But there is just no denying it: the book is terrible.”

A.N. Wilson, writing in the Times, labelled the Rees-Mogg opus “staggeringly silly” and revealed how “you start to think the author is worse than a twit”.

Perhaps the most withering put-down came from the august pages of the Times Literary Supplement, which declared simply, “we are not reviewing it in the TLS, preferring to focus on books that engage with the subject seriously”.

I looked hard for positive reactions, or even just one that wasn’t hurling it out of the nearest window in a disgusted flurry of pages, but it was a struggle. Amazon has a fair number of reader reviews, nearly all of them negative, nearly all of them from people who clearly haven’t read the book, but I did locate a couple of literary high-fives among the pompous dismissals and gleeful sneering.

“Unputdownable and, yes, sometimes a little controverical version revisionists (Remainers?),” gushed one, flinging out a random scatter of words and nearly-words like grapeshot from a blunderbuss.

“I actually only bought this book as the left-wing media had so criticised it for writing anything positive about the British Empire and its builders and heroes,” said someone heroically shelling out cash for terrible books in order to teach those pesky lefties a lesson.

Other than those two hymns of reasoned praise, however, it’s pretty much wall-to-wall pannings that reduce the poor publicity department at W.H. Allen to posting comments cooing over the author’s tailoring in the section set aside for quotes from published reviews.

Of all the blisteringly hilarious barbs I unearthed, it’s an almost throwaway line in Sandbrook’s piece that really stood out for me. The Victorians, he writes, is a book “so bad, so boring, so mind-bogglingly banal that if it had been written by anybody else it would never have been published”.

Ain’t that the truth. It’s understandable that the Penguin imprint would have commissioned The Victorians. Rees-Mogg is a topical figure; he carries on like he’d still use a bathing carriage at the seaside; the book was timed to coincide with the bicentenary of Queen Victoria’s birth; and the author, at least in his public pronouncements, has an air of learning and erudition.

You can almost hear the smack of high-fives among the sales and marketing team in the commissioning meeting. Yet instead of turning out a fresh and thought-provoking take on the Victorians, written with flair and panache, Rees-Mogg has merely confirmed that a) writing a book is far more difficult than it looks, and b) privilege might breed colossal self-confidence but it doesn’t automatically bestow even a basic level of competence.

Take his chapter on W.G. Grace, in which I was particularly interested as I’ve written a book about the Victorian cricketing colossus myself and was curious about what Rees-Mogg might have to say about him. The answer is: nothing new. In fact, nothing of note at all. It’s not badly written, it’s certainly not brilliantly written, just utterly unexceptional; a straightforward regurgitation of a handful of secondary sources which, from a man with a degree in history from Oxford, is inexcusable.

There’s no freshness to the material and the prose is entirely free of any insight, individual thought, analysis or the merest hint of stylistic flourish. This book is essentially what you’d end up with if you put Wikipedia through seven years at Eton.

Rees-Mogg appears to have received an advance on royalties of £25,000, inasmuch as he has so far declared £12,500 to the parliamentary register of interests in connection with his book deal (most likely the amount he received on signing the book contract, usually 50% of the total advance).

If that’s correct it’s a significantly smaller amount than I’d have expected, although Penguin are not renowned for their huge advances. Even so it makes the flaccid, self-serving nature of the resultant book no less frustrating.

In 2018, according to the Authors’ Licensing and Collection Society, the median income for a professional author was £10,500 a year, or two-and-a-half Jacob Rees-Mogg book deals. Writing books is not generally something from which you expect to end up lighting cigars with £50 notes or even, for most writers, make anything like a decent living. Writing a book takes up a huge amount of time, researching, writing, shaping, editing, revising: it’s a tricky business and one that involves a lot of work with no guarantee of success or even a half-decent financial return at the end of it.

Not all of those median-income professional authors are shivering in a garret somewhere, trying to eke out what at an hourly rate works out at two quid below the national minimum wage. Most of us take on other work, some have partners or spouses who are able to prop things up financially, others have financial independence through other means, which all goes a long way to explaining why in general we don’t see enough books appearing from working-class authors.

There is a sense of that changing, however, as the industry is gravitating towards writers who aren’t from a background of privilege.

Take the current explosion of brilliant fiction writers coming out of Ireland, for example: there’s surely a direct correlation between this crop of outstanding young novelists – Baileys Prize-winner Lisa McInerney, Paul McVeigh and Sally Rooney to name but three – and the recession that followed the financial crash of 2008.

Writing a book of any kind takes three things: time, quiet and solitude which, for most people, are impossible luxuries. When there’s no work the first of the three at least becomes plausible.

The British-Irish writer Kit de Waal, who grew up in a working class area of Birmingham, used part of the advance from her first novel My Name Is Leon to set up the Kit de Waal Creative Writing Scholarship, a fully-funded place on the Birkbeck College MA in creative writing with a travel bursary and funds to buy books for a person from a disadvantaged background.

She also compiled Common Ground, a collection of essays and poems from a range of working class writers including McInerney, Stuart Maconie and Cathy Rentzenbrink. There’s a long way to go before publishing becomes a meritocracy but these are all encouraging signs of tangible progress.

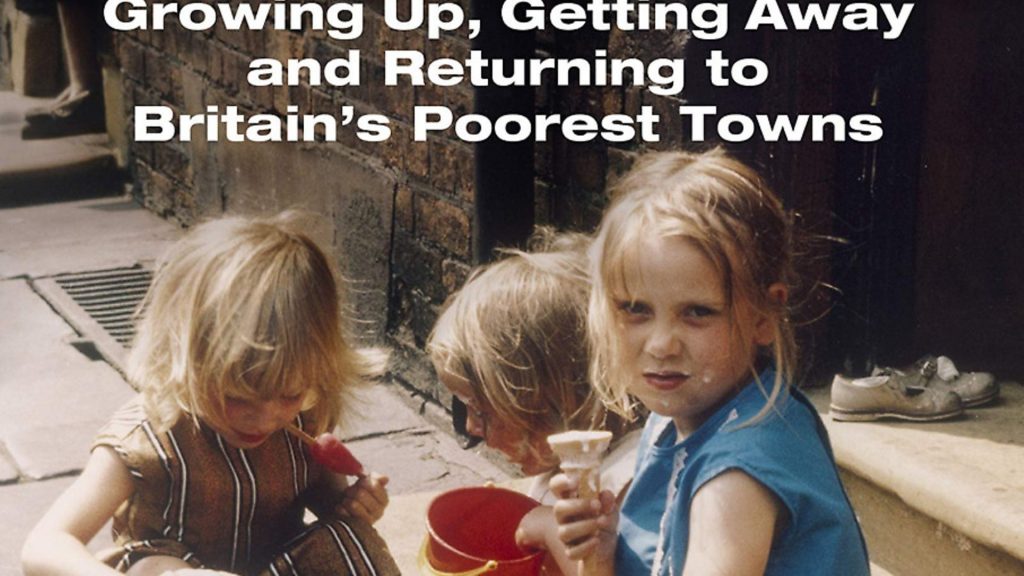

In the same week that Rees-Mogg’s book was published came Kerry Hudson’s astonishing Lowborn: Growing Up, Getting Away and Returning to Britain’s Poorest Towns (Chatto & Windus, £14.99), a stunning memoir and personal exploration of poverty in Britain today. Having grown up poor and bewilderingly disadvantaged in towns the length of Britain, from Aberdeen to Canterbury, Hudson has seen the worst of the nation and, very occasionally, some of the best.

Lowborn is the perfect literary riposte to the lazy, half-interested exercise in self-puffery produced by Rees-Mogg and one that counters perfectly the kind of lazy assumptions about the poor that are rife among his ilk.

“From the age of fourteen to my fast-approaching thirty-eighth I have never not worked,” Hudson writes, listing “call centres, a Harrods Christmas elf, plenty more waitressing, chambermaiding, shop work, cleaning toilets, street fundraising, nannying, care work, eventually work with charities, from answering the phone to being responsible for raising a million quid. And all the while I listened to people, who’d never lived a day of the sort of life I’d had, say my sort were workshy and scroungers.”

Lowborn is a rallying cry against the prevailing narrative that condemns the poor as failures. In fact, it is in many ways a modern evocation of the realities of the Victorian era completely ignored by Rees-Mogg.

Hudson notes how “it is in many people’s interests for the poor to stay poor, for the communities I came from to be made to believe they deserve nothing better, for a large proportion of the population to believe that if you are poor then you are somehow undeserving of empathy. That somehow poverty is a personal choice or failing and had you only worked hard enough you might have avoided the fate of daily unrelenting hardship.”

These are lines that could plausibly have come from The Victorians, had it been a book that involved any depth of research or critical thinking whatsoever, yet they were written on the threshold of the 21st century’s third decade by someone who has effectively lived the Victorian experience, only with slightly better plumbing and microwave meals.

It’s voices like Kerry Hudson’s that we need to hear more from, people who can really write and who have something to say, something lived, something with heart, redemption and epiphany. Voices with depth and intelligence and nuanced thinking who can tell the rest of us, whether through fiction or memoir, this happened, it happened to me, it isn’t right, it shouldn’t have happened then and it shouldn’t be happening now.

Those voices are out there. Until there are structures in place to find them, encourage them and invest in them then we’ll be stuck with the half-baked, ill-informed ramblings of Jacob Rees-Mogg. We need to hear less lazy thinking from feckless Old Etonians unwilling to put in the graft required to produce a book worthy of a reader’s time and money, and more from the intelligent and hardworking, the writers prepared to put in the hours to produce books as worthwhile and enlightening as Kerry Hudson has with Lowborn.

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37