Among the many abiding images from Britain in 2020 some of the most memorable are of the packed summer crowds on the beach at Durdle Door in Dorset. Scorching temperatures combined with the cancellation of holidays abroad to have people throwing social distancing to the breeze and flocking in their thousands to the coast.

The beach near Lulworth Cove was more packed than most, not least when everyone had to be corralled into one area to allow an air ambulance to evacuate people injured jumping into the sea from th

e cliffs. The remarkable stone arch extending into the sea became an unwitting symbol of coronavirus irresponsibility in Britain.

Two hundred years earlier two men had walked the same sands and marvelled at the same geological quirk of the Channel shore. This time there was no global pandemic (although the spectre of deadly illness was hanging over them), they had the beach to themselves and nobody was jumping off the cliffs.

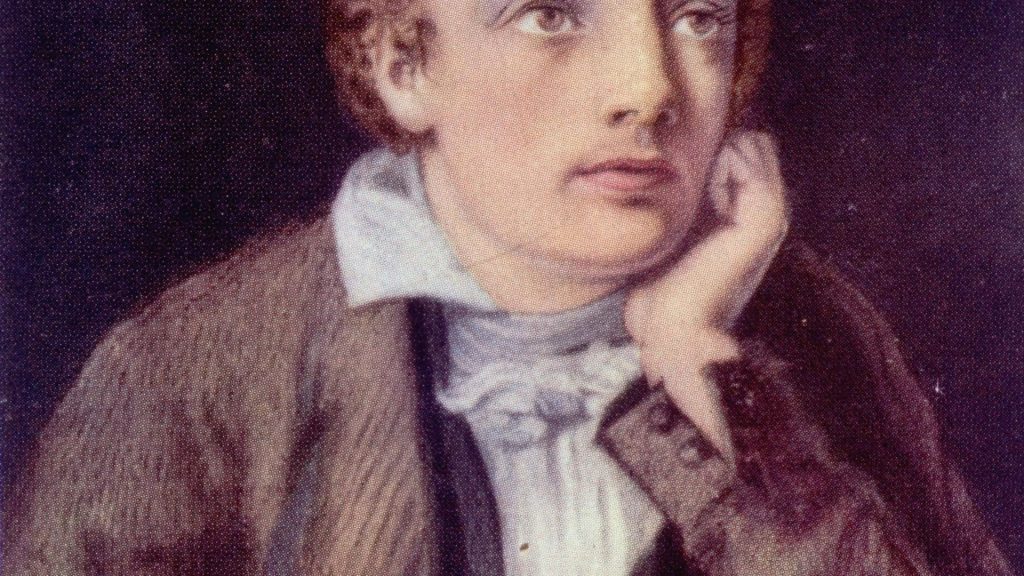

It would not have been an occasion of any particular note, except that on that day two centuries ago this month one of them was standing on British ground for the last time. He was 24 years old, he was riddled with tuberculosis and had that summer just published one of the greatest volumes of poetry in the history of literature in English.

In October 1820 John Keats was on his way to Italy having been advised that the Mediterranean climate would be beneficial to his health, but he’d long suspected the prospects of his recovery were unrealistic.

“I know the colour of that blood: it is arterial blood. I cannot be deceived in that colour,” he’d told a friend in February after coughing up blood for the first time. “That drop of blood is my death warrant. I must die.”

Tuberculosis had taken his mother, uncle and a brother meaning Keats, who had studied medicine himself, was under no illusions as to the gravity of his situation.

Since the spring of 1819 he had been on an unprecedented creative high, inspired partly by a walk on Hampstead Heath with Samuel Taylor Coleridge and partly by his increasing passion for Fanny Brawne, to whom he would become secretly engaged. He wrote two of his finest works, La Belle Dame sans Merci and the Ode to Psyche, in the space of a few days at the start of April, followed by the magnificent Ode to a Nightingale, inspired by hearing the bird sing close to his home at Wentworth Place. Close behind came Ode on a Grecian Urn and Ode on Melancholy, some of the greatest and most enduring verse in the English canon and all written in a short, intense burst of creativity in April 1819.

He spent most of the summer at Shanklin on the Isle of Wight working on Lamia, an epic retelling of a tale from Greek mythology, then moved on to Winchester where in mid-September he wrote his Ode to Autumn, the “season of mists and mellow fruitfulness”, composed after a day spent walking in woodland close to his lodgings. Much anthologised, it’s arguably the finest of his shorter works and represented the final cadence of this brief flowering of extraordinary poetry.

An incredible legacy it may be today but the poems were little help to Keats’ dire financial straits at the time. He spent the winter in London reworking a long term project, the Miltonic epic Hyperion that he would later abandon, and attempting to write plays for the London stage.

All the while he was aware of his fluctuating health. That first experience of coughing blood in February 1820 had followed a freezing late night journey from central London to Hampstead that Keats had endured on the outside of the coach because he couldn’t afford to travel inside, and such haemorrhages became increasingly regular. Despite this, in April he managed to submit his new poems to his publisher Taylor and Hessey, subsequently working on the proofs of this new collection.

When Lamia, Isabella, The Eve of St Agnes, and other Poems was published in June 1820 Keats would have been nervous about its reception. Two years earlier Taylor and Hessey had published his Endymion, the story of the relationship between the Greek moon goddess and the eponymous mortal of the title and a work savaged by the critics. Blackwood’s Magazine dismissed “the calm, settled, imperturbable drivelling idiocy of Endymion” and, referring to Keats’ previous employment as an apothecary, suggested, “It is a better and easier thing to be a starved apothecary than a starved poet; go back to the shop, Mr. John, back to plasters, pills and ointment boxes”. The Quarterly Review, meanwhile, said it had tried to get through the poem but abandoned it after the first of the four books, asking anyone who actually managed to finish Endymion to get in touch.

So awful was the criticism that a myth subsequently developed blaming the critical reaction to Endymion for hastening Keats to an early grave. In Don Juan, Byron writes of “John Keats, who was killed off by one critique, just as he really promised something great”.

To his credit Keats faced up to the barbs and in his new volume identified himself on the title page as “the author of Endymion”. And the reviews were excellent.

“Eminently beautiful,” said the Scots Magazine, the reviewer adding of Ode to a Nightingale that “we have read this ode over and over again, and every time with increased delight”. For the London Sun, “the story of Isabella, from Boccaccio, is a specimen of beautiful simplicity and affecting tenderness; the smaller poems especially the odes to a nightingale and a Grecian urn, deserve high praise”.

By the time the collection appeared however Keats’ health was fading more rapidly. As those glowing reviews of his finest work were being written his doctor recommended a move to Italy, where the more pleasant climate might ease his suffering. On September 17, 1820, accompanied by the artist Joseph Severn, Keats stepped off the quayside by the Tower of London onto the two-masted brig Maria Crowther, under Captain Thomas Walsh, to sail for Naples.

The ship called at Gravesend, where Keats sent Severn ashore to procure medicines including a bottle of laudanum, but once they reached the English Channel the voyage was beset by delays, a cycle of storms being followed by a total absence of wind. After ten days on board, with Keats and Severn sharing quarters with a Miss Cotterill, also suffering from consumption, the Maria Crowther had only reached Portsmouth.

In the first week of October the ship was forced to shelter close to shore again, this time hugging the coast of Dorset. Severn’s account of the journey is a little unreliable – he confuses Dorchester with Doncaster, for example – but he was afflicted with seasickness so severe that one passenger whispered of him and Keats, “which is the dying man?”. His memoirs suffered further from some rather liberal editing in the late 19th century, but it’s almost certain that he and Keats went ashore at Lulworth Cove and visited Durdle Door.

“Arriving on the Doncaster [sic] coast Keats was persuaded to land with me & for a moment he became like his former self,” he wrote. “He showed me the splendid caverns & grottos with a poet’s pride, as tho’ they had been his birthright.”

It was Thomas Hardy who in 1914 identified Durdle Door as the most likely location of Keats’s farewell to England.

“’Grottoes’ is certainly rather an exaggerated description of what one finds at Durdle Door, and Stair Hole close by, yet an enthusiastic young Londoner might on a first impression use such words,” he wrote to Keats’ biographer Sidney Colvin. “Besides, if not Durdle Door, Stair Hole, &c., what place can it be that Severn meant? The ‘Door’ is an archway in the cliff, as you know: Stair Hole has caves & fissures into which the sea flows, & there is another cave at Bat’s Corner, also close at hand. At any rate I cannot think of another point on the Dorset coast, easily accessible from a boat, which so well answers the description.”

Keats’ last experience of England, 200 years ago this month, was at any rate an uplifting one. The pair watched as darkness fell and the stars came out over the sea as the waves washed onto the shore. So enamoured was Keats by the experience that when the pair returned to the Maria Crowther he took Severn’s copy of the complete works of Shakespeare and wrote out his sonnet Bright Star on a flyleaf, which begins

Bright star! would I were stedfast as thou art—

Not in lone splendour hung aloft the night,

And watching, with eternal lids apart,

Like Nature’s patient, sleepless Eremite,

The moving waters at their priestlike task

Of pure ablution round earth’s human shores

Severn was under the impression Keats composed the poem on the spot but he’d been working on it since the previous year, inspired by his love for Fanny Brawne. Either way, the version Keats wrote down that night while moored under the stars within sight of Durdle Door became the definitive version of one of his most beautiful works.

The Maria Crowther struggled on around Europe’s Atlantic coast and did not reach Naples until October 21. Thanks to reports of a typhus outbreak in London the passengers and crew were then forced to remain on board quarantined for ten days, meaning that Keats finally set foot on Italian soil on October 31, his 25th birthday. Passport issues delayed his arrival in Rome for a further fortnight, by which time winter was closing in and the opportunity for the ailing poet to benefit from a milder climate had gone.

Keats died at the villa he’d taken by the Spanish Steps on February 23, 1821. He was buried in the protestant cemetery having left instructions that his grave be marked with the epitaph, “Here lies One whose Name was writ in Water”.

Hardy’s correspondence with Colvin about the location of Keats’ farewell to England led to a poem written exactly a century ago, a century after Keats’ brief sojourn ashore on the Dorset coast. In At Lulworth Cove a Century Back Hardy imagines walking to the cove in 1820 to see “One that boat has brought, which dropped down Channel round Saint Alban’s Head”. In the poem, time itself points out Keats to Hardy, who muses on how the consumptive poet would have looked entirely unremarkable, “Of an idling town-sort; thin; hair brown in hue; And as the evening light scants less and less, he looks up at a star, as many do”.

In the final stanza, time instructs Hardy of the significance of the man down on the beach marvelling at the geological wonder of Durdle Door and exhilarated by the canopy of stars overhead.

That man goes to Rome — to death, despair;

And no one notes him now but you and I:

A hundred years, and the world will follow him there,

And bend with reverence where his ashes lie.

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37