CHARLIE CONNELLY on the life of Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn – the face of resistance to Soviet state oppression.

He looked apprehensive in the doorway of the Alaskan Air jet that had just landed in Magadan, on the Sea of Okhotsk in eastern Siberia, from Anchorage. His eyes darted from side to side as the wind toyed with his beige raincoat and pulled at his Tolstoyan beard. For a brief moment he appeared reluctant to disembark, then pulled back his shoulders, lifted his chin and descended the stairs, hands gliding over the handrails. At the bottom he took a few steps forward and stopped in front of the assembled journalists, glassy-eyed, as if looking through them. He was engulfed by people, lenses in his face, the young woman in traditional costume there to present him with the customary Russian welcome of bread and salt trying to preserve her immaculate smile as she was jostled by men with cameras and Dictaphones.

In the middle of the mêlée Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn stood impassively. He breathed in deeply, exhaled slowly, bent forward from the waist and laid the palm of his right hand on the tarmac in confirmation that yes, he really was standing on Russian soil for the first time in two decades. He could have flown directly to Moscow but instead chose a circuitous route. If he was to return to Russia, it was to be to the whole of Russia. That’s why he touched down in a small, out of the way airport on the eastern fringe of the country at the end of May 1994.

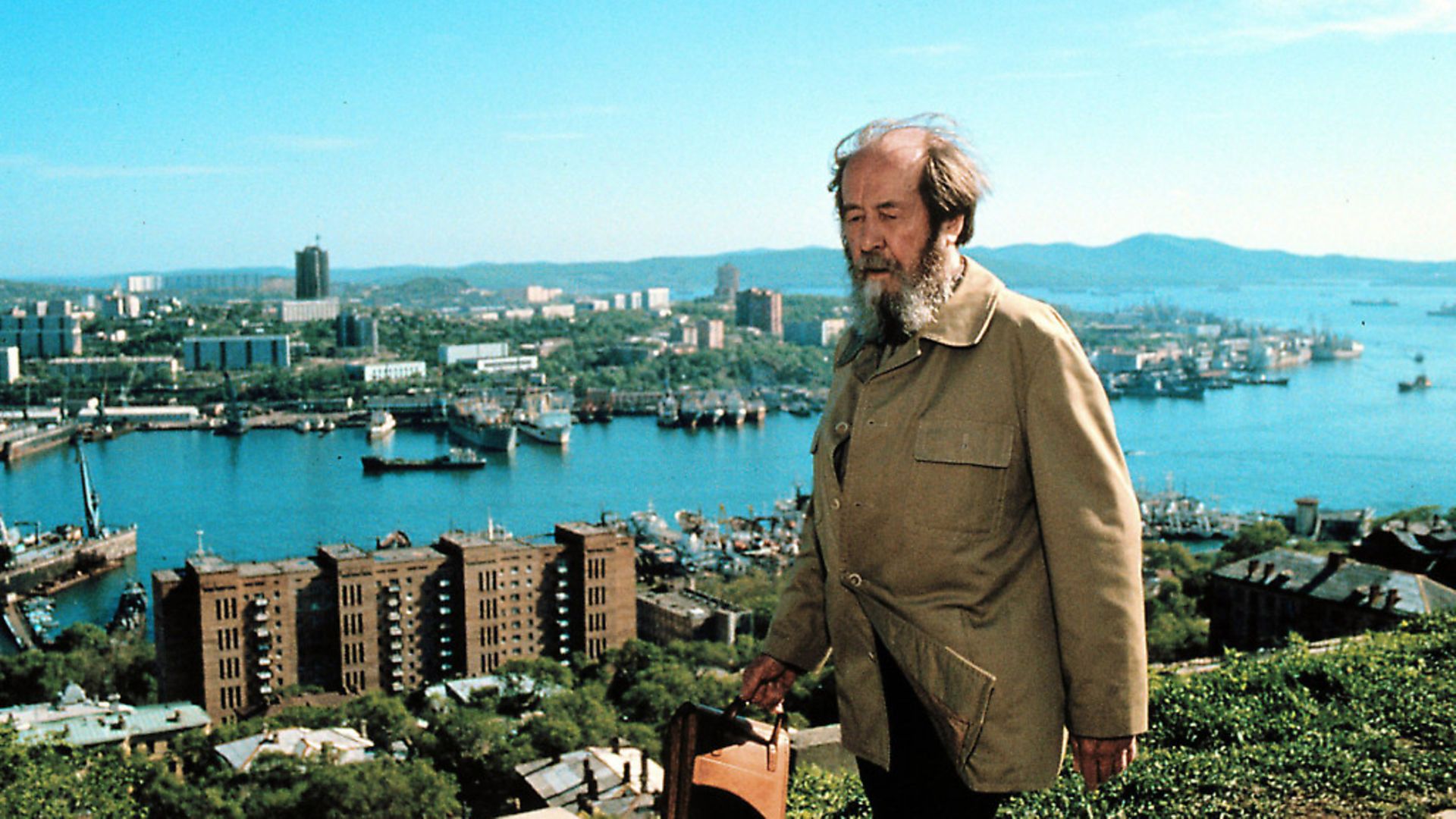

From Magadan Solzhenitsyn was flying on to Vladivostok, where he would board a train and cross the entire country, stopping regularly to greet well-wishers before arriving in the capital city he’d last seen from the aircraft that deported him on February 12, 1974.

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn was one of the key figures of the Cold War. His writing, and his epic history of Stalin’s labour camps The Gulag Archipelago in particular, made him the face of resistance to Soviet state oppression.

Indeed, it was the publication of The Gulag Archipelago that had sealed his expulsion. Written over several years during the 1960s it ran to more than 300,000 words and by 1973 had made it to publishers in Paris and New York on microfilms smuggled out of the USSR.

Solzhenitsyn had planned for the book to be published unofficially in the USSR first, but in September 1973 the KGB forced his hand by taking possession of a microfilm after interrogating the author’s copy typist Elizaveta Voronyanskaya, who was found dead shortly afterwards in an apparent suicide.

The foreign editions went ahead almost immediately, lifting the lid on the Soviet system of forced labour camps for the world to see. Solzhenitsyn was expelled within weeks of the book’s publication, arriving in West Germany in February 1974, moving on to Zurich before settling in a small town in Vermont where he remained as a virtual recluse for 18 years.

In many ways Solzhenitsyn, once a poster boy for Stalin’s education system, made an unlikely thorn in the Soviet side. Born into a privileged family a year after the Bolshevik Revolution, he grew into an ardent, tubthumping Marxist-Leninist. His father had been a decorated officer in the Russian imperial army during the First World War but was killed in a hunting accident six months before Solzhenitsyn’s birth. His mother came from wealthy stock – an uncle owned one of only nine Rolls-Royces in the whole of Russia – but the revolution and widowhood handed her a frugal life in which she supported her son by working as a typist.

Solzhenitsyn became an enthusiastic member of Komsomol, the Communist Party youth movement, and embarked on a mathematics degree alongside a diploma in literature.

The epitome of communist youth, Solzhenitsyn’s intellectual achievements in the name of the revolution saw him awarded a prestigious scholarship that carried Stalin’s name, one of only eight awarded across the Soviet Union.

‘From childhood I had somehow known that my objective was the history of the Russian Revolution,’ he wrote. ‘To understand the revolution I had long since required nothing beyond Marxism. I cut myself off from everything else.’

When the USSR joined the Second World War Solzhenitsyn became captain of an artillery unit in East Prussia. Even in the midst of war his passionate belief in communism never dimmed, and didn’t stop him having reservations about aspects of Stalin’s leadership either. When he expressed those reservations in a letter to a friend it was more than enough to have him arrested.

At first his naïve faith in the intellectual purity of the Soviet Union convinced Solzhenitsyn he was being taken to Moscow to discuss his ideas, but once in the capital he found himself first in the Lubyanka prison, then sentenced to the eight years in the labour camps that would come to define his life.

His mathematics qualification saw Solzhenitsyn transferred to a sharashka, as much a scientific research centre as a labour camp, where he found himself among other intellectuals tasked with producing a telephone scrambling device. There was an incongruous level of incarcerated freedom in the sharashka: Solzhenitsyn and his fellow exiles were able to discuss politics, read a wide range of literature and even listen to BBC broadcasts on the radio.

It was here that his thinking was transformed. He abandoned his Marxist convictions and withdrew from the telephone project in favour of manual tasks. The sharashka requiring a mathematician not a woodcutter, he was soon transferred to the labour camp at Ekibastuz in Kazakhstan. His three years there would later be fictionalised in his novel One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich.

In 1953 Solzhenitsyn was released into internal exile in Kazakhstan just as news of Stalin’s death emerged. Khrushchev’s less oppressive form of leadership led to Solzhenitsyn’s rehabilitation and by the dawn of the 1960s his work was being widely read in editions published unofficially yet broadly tolerated. In 1962, with Khrushchev’s personal approval, One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich was published in the anti-Stalinist journal Novy Mir. The closest there had ever been to a warts-and-all account of the gulags, Ivan Denisovich was a sensation: Solzhenitsyn was elected to the Soviet Writers’ Union, nominated for the Lenin Prize and credited with the rebirth of literature in the USSR.

When Khrushchev was removed in 1964, however, and replaced by the more authoritarian Leonid Brezhnev, Solzhenitsyn found himself out in the cold again. He worked tirelessly in secret on The Gulag Archipelago and set his sights on the Nobel Prize for Literature, becoming obsessed with winning the award that Boris Pasternak had been forced to turn down in 1957.

‘All the more vividly did I see it, all the more eagerly did I brood on it, demand it from the future. I had to have that prize,’ he wrote. ‘My actions would be the opposite in every way of Pasternak. I should resolutely accept the prize, resolutely go to Stockholm and make a very resolute speech!’

Awarded the prize in 1970, however, Solzhenitsyn was unable to make his speech: he was embroiled in a messy divorce at the time as well as the birth of his son.

By then he had burnt literary bridges at home. In 1967 he’d written to the Writers’ Union insisting their Congress ‘demand and ensure the abolition of all censorship, open or hidden’. He was expelled from the organisation two years later, setting in motion the process that ended with his deportation.

On that epic 1994 train journey across Russia he found his homeland ‘tortured, stunned, altered beyond recognition’. In Moscow he soon became disillusioned with the crime, corruption and the decline he saw of the Russian spirit he’d always sought to safeguard against oppression.

In an echo of his wartime arrest, Solzhenitsyn had expected to be feted and consulted by the new political elites but his opinions regarding the way forward were never solicited. It was June 2007, a year before his death at the age of 89, before any Russian leader saw him when he was visited by Vladimir Putin. What he might think of the current Putin regime is perhaps hinted at by something he told journalists that day on the apron at Madagan.

‘The people are not the masters of their own fate,’ he said, ‘and so we cannot talk about democracy.’

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37