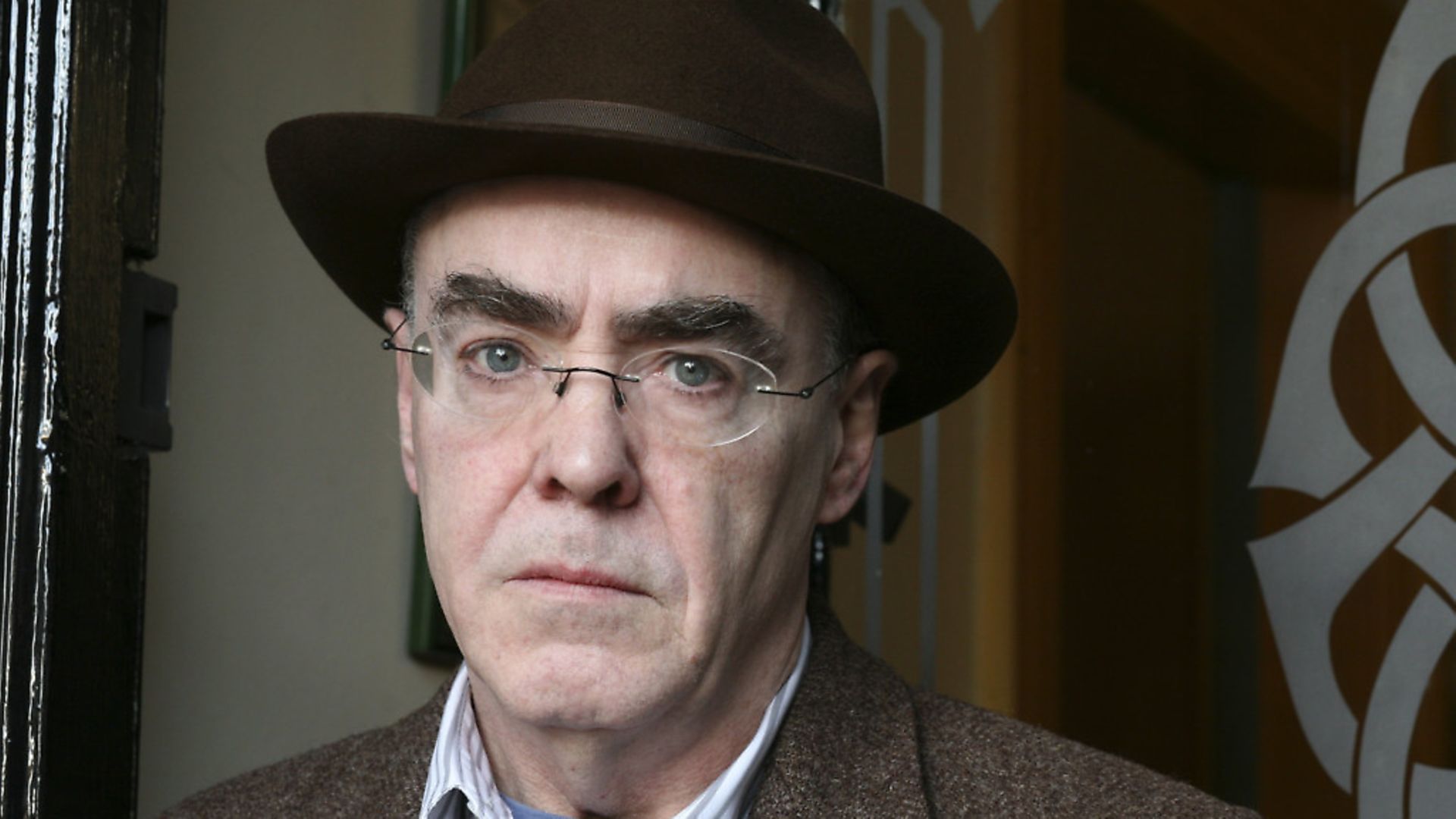

CHARLIE connelly on the death of a poet who chronicled his city’s epic story.

There was something terribly poignant about how Ciaran Carson, who died on October 6, left us just when Northern Ireland was anchored to the top of the British news agenda for the first time in two decades. Diagnosed with terminal lung cancer last spring, the poet died three days shy of his 71st birthday and barely a fortnight before the publication of what turns out to be his last collection, Still Life.

Ciaran Carson was a Belfast poet both in that he was born and lived his entire life in the city and that his verse was absolutely steeped in the place, an infusion that characterised the 14 volumes of poetry he published during his lifetime as well as his idiosyncratic, insightful prose output.

He’s arguably best known for the title poem from his 1989 collection Belfast Confetti, a vivid encapsulation of life during the Troubles that combined imagery of war with Belfast slang and tradition: the ‘confetti’ was originally the detritus of nuts and bolts that littered the city from its shipyards but from the late 1960s the phrase came to encompass the shrapnel and debris left by bomb detonations.

“Suddenly as the riot squad moved in it was raining exclamation marks, nuts, bolts, nails, car-keys. A fount of broken type,” the poem begins, before the narrative voice finds itself suddenly aware of and compressed by its boundaries.

“I know this labyrinth so well – Balaklava, Raglan, Inkerman, Odessa Street – Why can’t I escape?”

Carson was born on Raglan Street in the Falls Road area of west Belfast in 1948, the son of a postman and a linen factory worker.

“It was jam-packed with small shops and small streets crammed into each other,” he recalled of the neighbourhood in which he grew up. “Pawnbrokers, haberdashers, fleshers; it was a shop and a shop and a bar, a shop and a shop and a bar, and each had its own array of who went there, so even though it was a small world, it was still huge.”

He was used to being in a divided community from the start as his particular square mile was divided more than most. As well as living in an enclave of streets occupied by Catholic families a few minutes’ walk from the Protestant Shankill Road, Carson’s was one of barely a handful of households in the entire city where Irish was spoken as a first language.

His parents had met when Carson’s mother had attended Irish language classes taught by his father and the couple decided that Irish would be the language spoken in the family home. Although Irish was not officially recognised in the North until the era of the Good Friday Agreement it wasn’t quite as political a statement in Carson’s youth as it would have been during the Troubles, marking the five young Carson siblings out as merely unusual among the English-speaking kids playing endless games of football and hurling in the street (Carson was a gifted hurler who made the Antrim county minor team, roughly the equivalent of a professional football club’s Under-23s).

He was in his early 20s when the Troubles began in earnest, British troops appearing on the streets to transform them into a bizarre and deadly combination of war zone and ordinary domesticity, all net curtains and ArmaLites. Random searches and on-street interrogations became commonplace, as Carson writes in Belfast Confetti:

“A Saracen, Kremlin-2 mesh. Makrolon fae-shield. Walkie-talkies. What is/My name? Where am I coming from? Where am I going? A fusillade of question-marks.”

He would often recall the surges of resentment he felt when pushed up against a wall by a squaddie demanding in a cockney accent to know where he was from.

“I’m from here,” Carson would say of streets where he knew every crack in every paving stone, responding to a nervous teenager in an ill-fitting helmet who would still struggle to point to Belfast on a map.

Even his name was a division symptomatic of the city and country that made him, with Ciaran coming from a Catholic Irish tradition and Carson being a solidly Protestant surname. In a tribute following Carson’s death the novelist John Banville described him as a Shakespearean hybrid, part Puck, part Ariel, and recalled how, “back in the bad old days of republican and loyalist roadblocks he used to joke that his name ensured him immunity on both sides”.

It also gave him a strange combination, invaluable in a poet, of simultaneously belonging everywhere yet always being the outsider. He first found his poetic voice as a student at Queen’s University in Belfast, where was taught by Seamus Heaney.

While at Queen’s he became associated with the Belfast Group of poets, somewhere he definitely belonged as part of an extraordinary flowering of poetic talent whose original participants included Heaney, Michael Longley and Derek Mahon.

Carson was part of a younger second wave along with the likes of Paul Muldoon and Medbh McGuckian, exchanging and sharing ideas and poems, each developing as an individual creative force while remaining part of a loose collective.

After graduating Carson took a job with the Arts Council of Northern Ireland, spending 20 years as the organisation’s traditional arts officer. The post allowed him to indulge his other major talent and passion as a musician: he was a gifted flautist and tin whistle player in the Irish folk tradition and as part of his Arts Council role would travel the country visiting, organising and participating in music events and sessions.

It’s how he met his wife Deirdre Shannon, a fiddle player, and many of Carson’s poetry readings would be interspersed with tunes and songs performed by the couple.

He was an authority on Irish traditional music and expressed his passion for it in the book Last Night’s Fun, published in 1996 and still one of the best books ever written about any musical genre. Mixing history, biography and personal anecdote, Last Night’s Fun is also a brilliant evocation of Irishness through the comradeship of its musicians.

A memorable chapter details the morning after a session with the musicians, waxy-faced, hungover and bleary after waking up on someone’s floor, heading out in search of a breakfast fry-up. Their ears still ring with the music, their fingertips still thrum from the previous night’s playing, their instruments silenced in cases slung over their shoulders or carried under their arms but the tunes still echoing around their heads as they turn up coat collars and thrust hands deep into pockets. The chill of the morning air is in contrast to the immersive warmth of the previous night’s activities and when they finally find a café and order their breakfasts you can almost smell the frying bacon and breathe in the fug of condensation.

“You are in tune with what goes on,” he wrote of musical performance. “Time accelerates or contracts. We make a contract with it to pretend that it will never overcome us.”

His sense of rhythm, developed through endless sessions and recitals, was another key ingredient of his poetry which combined with his linguistically unusual background to give Carson a finely-tuned ear for language and an acute awareness of its power.

His love for language also inspired him to publish widely-praised and award-winning translations of Dante’s Inferno and the early Irish epic poem the Tain, the legend that tells of how Medbh, the Queen of Connacht, led a raid into Ulster in search of the prize brown bull of Cúailnge only to be repelled single-handedly by the young warrior Cú Chulainn.

Carson’s death deprives the whole island of Ireland of one of its finest poets and most distinctive writers. It’s no surprise that he emerged at the head of a flourishing burst of poetic creativity around the Troubles as his poet’s eye and immersion in the community gave him and his fellow writers a more nuanced perspective on a horrifically complex situation.

“If there’s one thing certain about what was or is going on it’s that you don’t know the half of it,” he said in 2009 about Northern Ireland’s complicated past. “The official account is only an account, and there are many others. Poetry offers yet another alternative. It asks questions about the truth, which is never black and white.”

He’d had at least one brush with death before, in 1969 when a bullet whistled through the Belfast taxi in which he was travelling, and most of Still Life, published this week, was written after his cancer was confirmed as terminal. It includes a meditation on the painting Lemons on a Moorish Plate by Angela Hackett that captures the mix of resigned anxiety and innate curiosity of a man contemplating his own imminent end:

It gave us pause for thought. How long does it take, we wondered, for a lemon

To completely rot? We imagined a time-lapse film, weeks compressed

Into seconds, the lemon changing hue, developing that powdery bloom, then

Suddenly collapsing into itself to leave a shrunken, pea-size, desiccated husk –

The flesh evaporated, breathed into the atmosphere as it transpires.

Such was Carson’s standing and reputation throughout the island of Ireland that the president of the republic, Michael D. Higgins, himself a published poet, issued a glowing tribute.

“He leaves such a wide body of work that people will have their own favourites, including the magnificent Belfast Confetti,” said Higgins. “Writing right up to the end, with the text forthcoming, he will be missed by all who had the privilege of knowing or reading his work.”

As Northern Ireland continues to be grievously, even deliberately, misunderstood and the brittle yet entrenched peace in the region treated with startling carelessness by Brexiters who still seem startled by the existence of the only land border they have to worry about, the loss of Ciaran Carson is thrown into even sharper focus. A wise, informed, eloquent voice of reason and enlightenment on the city and country that was his home, Carson was to Belfast what Heaney was to Derry and the city will feel his loss palpably, especially in the current political climate.

Maybe there’s solace in the opening poem of his 2010 collection Until Before After, in which he writes, “His last words/were the story is not/over”.

Still Life by Ciaran Carson is published this week by Gallery Press, price €11.95

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37