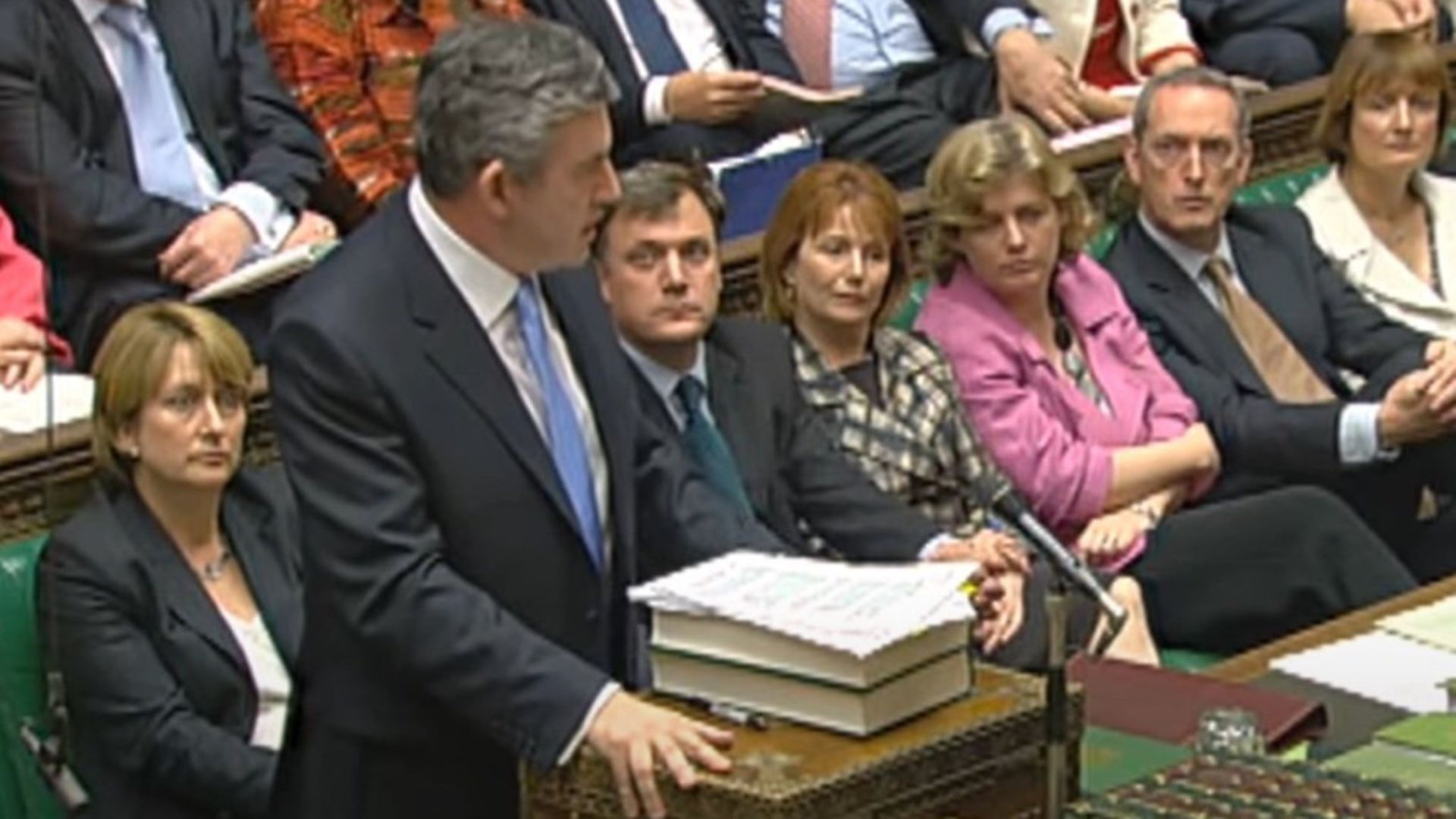

With no PMQs to review for a while, we look back on some classic encounters. This week it’s Gordon Brown’s first as prime minister

That Gordon Brown would succeed Tony Blair was a given, even more so than Keir Starmer succeeding Jeremy Corbyn. John McDonnell attempted to launch a challenge to the chancellor from the far left, but MPs were not prepared to lend him the nominations to get on the ballot.

Various Shakespearean disquisitions have since been written on the tragedy of a man obsessed with landing a job for so long that he’d forgotten to plan what to do with it, or how his eventual premiership would be solely defined by the financial crash (as Theresa May’s will be by Brexit, and Boris Johnson’s surely by COVID-19).

But, in these extraordinary times, what stands out now is the sheer, unbridled normalcy of 2007. New Labour reigned supreme, so unencumbered by ideology that The Thick Of It mined technocracy deep for laughs. David Cameron was considered a paltry figure. Indeed, Tony Blair dubbed him a ‘flyweight’ who faced electoral knockout by the ‘big clunking fist’ of a Labour ‘heavyweight’.

Nothing demonstrated how different it was than the very first question Brown faced as PM, from Daniel Kawczynski, Tory MP for Shrewsbury and Atcham. These days Kawczynski is known as one of the loopier Brexiteers, who attends conference with far-right figures and displays his commitment to sovereignty by attempting to use his contacts in the Polish government to veto a Brexit extension. In 2007 his indignation was also about the will of the people – that ‘the great men and women of Shrewsbury have spoken, and they have voted overwhelmingly against unitary authority status for Shropshire’. Brown looked like this was not what he had schemed for a decade to deal with. It was, he sniffed, a Conservative-run council which had proposed it.

His second came from Barry Gardiner, then as now Labour MP for Brent and, remarkably, looking even more like Timothy Claypole from Rentaghost than he does now. Gardiner, who asked about financial instruments for the protection of tropical forests, quickly embraced Brownism, before moving on to Milifandom and full-scale Corbynism. He should have a long time on the backbenches to plot his next ideological shift.

Brown’s first clash with Cameron was relatively subdued, given (unsuccessful) terror attacks in London and Glasgow in the previous week. Brown hoped ‘we can continue on an all-party basis to agree measures that are necessary in this country to deal with the terrorist threat’; Cameron hoped ‘that we can make progress’.

What followed was a fairly minor tussle over the banning of the extremist group Hizb ut-Tahrir (Cameron wanted it immediately, Brown needed ‘to consider all the evidence’) and ID cards (Brown very keen, Cameron not so much). They exchanged quotes from each other’s sides, the camera panning to an inscrutable Alistair Darling as Cameron reminded Brown his new chancellor had said ID cards were ‘unnecessary and will create more difficulties than they will solve’.

A little down the frontbench from Cameron sat its most civil libertarian and the man he vanquished to become leader, David Davis, who would go on the following year to resign as shadow home secretary for reasons he himself probably struggles to recall. Throughout the session his right arm remained draped around the back of shadow Welsh secretary Cheryl Gillan, the absolute lounge lizard.

Lib Dem – or ‘Liberal Party’, as Brown referred to them, a mere 19 years after their merger with the SDP – leader Menzies Campbell rose. Played as ever by the dancing skeleton from the 1980s Scotch video commercials, he asked for a target for the withdrawal of British troops from Iraq. Brown said that ‘my door is always open to the right honourable and learned gentleman’. Campbell responded that ‘it appears to be more of a trap door than anything’, and members across the house laughed uproariously like they’d just seen Delboy fall through the bar for the first time. Strange sense of humour, MPs.

But nothing summed up the different times like Shona McIsaac, who asked Brown if he would praise ‘the year five boys at Middlethorpe primary school in Cleethorpes for their wonderful ‘bully-buster’ initiative’. McIsaac was an uber-loyalist who lost her seat three years later and whose Twitter biography still begins ‘Labour MP for Cleethorpes 1997-2010’. There is, they say, nothing as ex as an ex-MP.

The session concluded with a question of flooding and, as Brown sat down and unrecorded by Hansard, various shouts of ‘Bring back Tony!’ shot out in the chamber. It’s not clear from the footage what side they emanated from.

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37