PETER HETHERINGTON looks back at the birth of Britain’s post-war new towns to see what lessons – of successes and failures – might help to address today’s housing crisis.

‘Our aim must be to combine in the new town the friendly spirit of the former slum with the vastly improved health conditions of the new estate… a broadened spirit embracing all classes…’

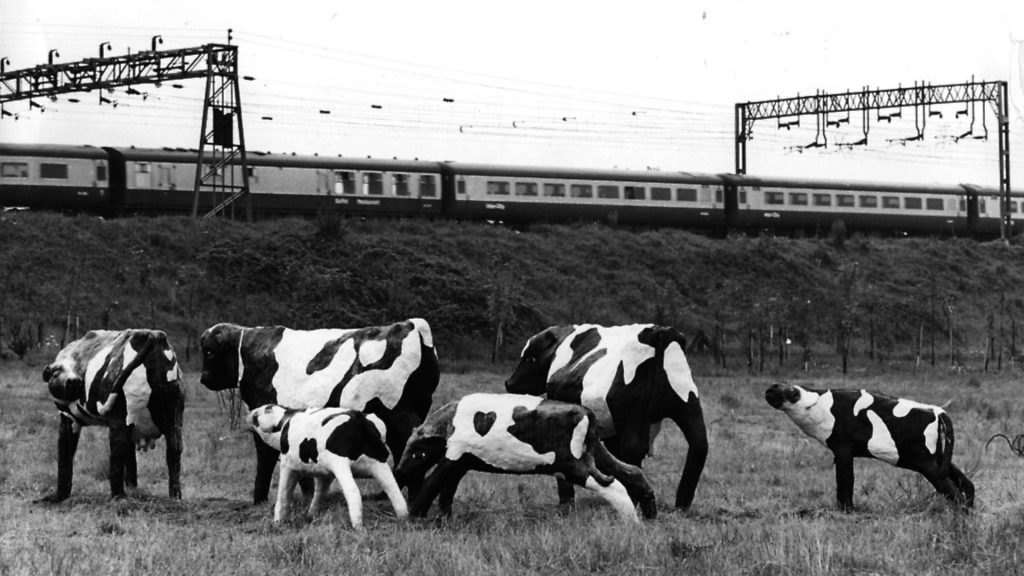

When he outlined plans for Britain’s first post-war new town at Stevenage in Hertfordshire, the minister of town and country planning certainly captured a national mood for radical change in 1946.

Defying protesters at a public meeting, Lewis Silkin thundered: ‘I want to carry out a daring exercise… It is no good you jeering. It is going to be done… the project must go forward.’

Passions were, briefly, running high. A few objectors deflated the tyres of his ministerial Wolseley. They daubed ‘Silkingrad’ on local road signs. Undaunted, the minister declared, perhaps over-enthusiastically: ‘People from all over the world will come to see how we in this country are building a new way of life.’

The rest is history: a ring of eight new towns around London, and then more across the UK – 32 in all – with a combined population of 2.8 million. They were underpinned by one overarching theme: active government, driven by a determination to deliver thousands of new homes to places like an expanded Stevenage, which now houses 86,000.

Development corporations were created to drive forward plans, armed with compulsory purchase powers to buy land at agricultural values so that the new communities could gain from the uplift in value as work progressed.

A raft of government ‘information films’, in the form of wartime propaganda, were produced as part of a national re-housing drive.

In one (A Home of Your Own) a fictional bricklayer from Willesden passes through an emerging Hemel Hempstead new town on a bus trip and asks, plaintively, why… ‘with all that space and air, people had to go on living as I did: me, the wife and kids in two rooms in London’.

In the real world, the reaction of one new resident (Anne Luhman) – moving to Stevenage in 1952 from a small flat in Tottenham, without running water – was typical: ‘A sink… my own bathroom… I felt I was on holiday for months and months.’

Amidst the post-war optimism, few queried the cost. Ministers insisted that, given time, the new towns would ‘pay for themselves’. And so, remarkably, it transpired. The remnants of a £4.57 billion loan was finally repaid with interest in 1999, according to a new book, New Towns – The Rise, Fall and Rebirth, by Katy Lock and Hugh Ellis. Not bad business, then?

But what subsequently emerged proved the antithesis of good business: the onset of state sell-offs, no matter the bargain-basement price, as privatisation became the over-arching mantra of the right.

New towns, as historian David Kynaston noted, became so linked with the ‘New Jerusalem’ aspirations of the post-war Labour government that Conservatives became hostile.

As Lock and Ellis recount in their book, which chronicles the unbounded optimism of a can-do- state through to the determination of a revolutionary Conservatism determined to break a post-war consensus, there was one fatal flaw in Silkin’s plan.

Because the development corporations – planning, building, administering the new towns – never had a life-span determined by law, they were susceptible to the whims of the free-market right.

This consequently left them ‘fatally vulnerable to a government determined to end the new towns programme,’ lament Lock and Ellis.

That inglorious end came in the early 1990s. A Commission for New Towns (CNT), residuary body for the development corporations, was told to sell its extensive portfolio of land and property. Consequently, the authors bemoan, ‘assets were sold before they had time to mature’.

Still, the 100th birthday of Welwyn (pop: 47,000) this year – the garden city that became the original new town – is an ideal time to reflect on the successes and the failures of an experiment which, at its best, pioneered an innovative concept of creating large, self-contained communities, copied internationally.

Welwyn has its roots in the nearby town of Letchworth, created as a ‘garden city’ by the visionary Ebenezer Howard in 1903 with his clarion call: ‘Town and city must be married and out of this joyous union will spring new hope, new life, a new civilisation’.

A former articled clerk, he found wealthy supporters to buy land for his new ‘city’, now with a population of 33,600. A charitable foundation still owns the freehold of land, plus surrounding farms, providing a multi-million pound surplus for community use each year. Quite a legacy!

Howard then turned his attention to acquiring nearby land. Welwyn Garden City was born in 1920. He created a private company and a talented young architect (Louis de Soissons) was appointed to plan a city of neo-Georgian buildings, elegant boulevards, and generous open spaces.

It was subsequently – unlike Letchworth – given new town status, making it susceptible to enforced land sales.

Today, at best, new towns have been consigned to history – for many, out of sight and mind, and, it seems, best forgotten as soulless, brutalist places, seemingly plonked randomly in the countryside.

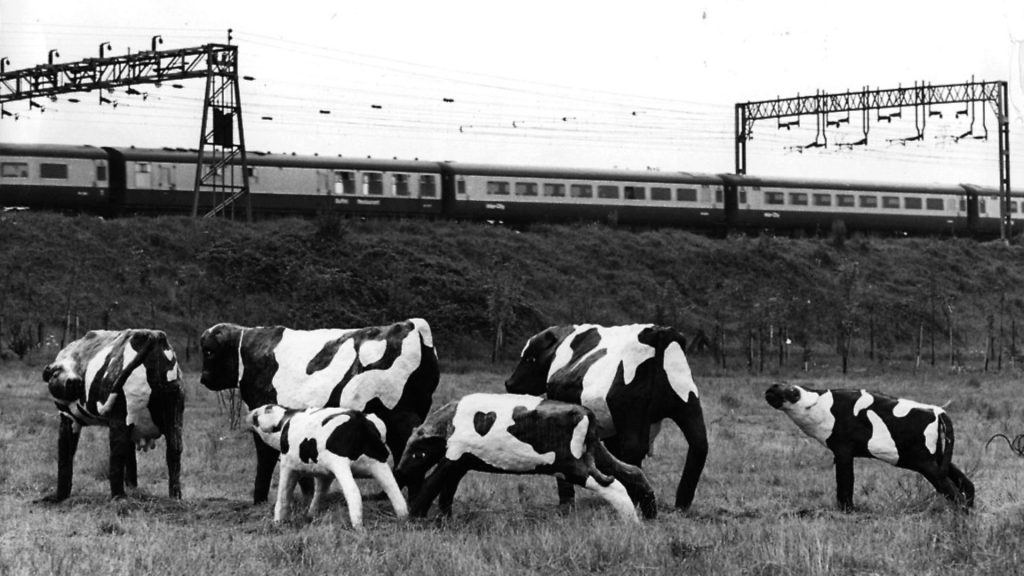

Milton Keynes, 54 miles north of London, last to be designated in 1967, now has a population approaching 220,000 and is probably the UK’s fastest growing town with a varied, largely service-driven employment base and a strong local economy – although its grid-system, and over-dependence on the car, is not to everyone’s liking.

Others, such as Harlow, in Essex, Hatfield in Hertfordshire and Bracknell in Berkshire, are in the process of renewal, while a few – Skelmersdale, in Lancashire; Peterlee in Durham; Glenrothes, in Fife, for instance – have seen better days and never fulfilled their potential.

In truth, there’s a big divide between the successful, particularly Milton Keynes, and the sadly neglected, such as Peterlee, in the old east Durham coalfield. ‘If an alien dropped in from above he’d have one look and say ‘this is a bit of a mess’,’ laments Ian Morris, chief officer of Peterlee Town Council, which has a tiny annual budget of just £3 million for a population of 20,000. His main gripe is the fragmented ownership of the town’s 12,000 hectares. The town centre – ‘abysmal’, says Morris – is owned by a distant property company with little interest in much-needed renewal. ‘They’ve just put up the rent and driven out the Citizens Advice Bureau which can’t afford it,’ he complains. Yet many locals still like the place. ‘I was born here – my mam and dad moved from nearby pit villages – and am very happy,’ says Helen, an office worker aged 54. ‘There’s lots of open space, nice walks and the sea is on the doorstep. Much nicer than the old pit villages.’

Katy Lock, born and raised in Milton Keynes 220 miles south, recalls a happy childhood and school years. ‘But I do seem to spend my life having to defend the town,’ she laughs while recounting the excitement of being in the first intake of pupils at brand new primary and secondary schools. Teenage years were fulfilling. Without music venues, Lock – director of communities at the Town and Country Planning Association – recalls that teenagers ‘made their own live music… it was like growing up in a village rather than a town… you were aware of growing up somewhere rather different.’

In nearby Stevenage, John Gardner remembers arriving in the new town as a young aerospace engineer in 1955. After spells in Australia, and the USA, he returned in 1996 to find a town transformed with a new shopping centre. Latterly, it has presented its own problems: the local borough council has had to spend millions buying back town centre sites – privatised from the 1980s – to renew the centre. ‘It’s quite a green town, with nice parks, gardens and a lake which is very popular,’ adds Gardiner, a local councillor, who led the town centre renewal.

Talk to other residents of Stevenage and an optimistic picture still emerges of young Londoners and their families moving from cramped slums in an overcrowded capital determined to make a better life in the green fields of Hertfordshire.

Sharon Taylor, leader of Stevenage Borough Council, was one of the first generation of Stevenage children born in the new town (in 1956) to parents who had left London for a better life.

‘I love the place of my birth,’ she noted on the 70th anniversary of Stevenage in 2016. ‘I am very proud of my new town heritage. I know people have called them concrete jungles, but they have largely stood the test of time, have delivered jobs, often strong economies, in pleasant surroundings.’

It’s here where we need reminding of the early ambition, and determination to confront an issue which bedevils development today: the price of land, and the impact of speculation, on plans for essential housing.

The new town pioneers were determined to reverse this ‘quick buck’ mentality by ensuring land was bought at mainly agricultural values. As Wyndham Thomas, former general manager of Peterborough Development Corporation for 15 year (who died this year, aged 95) explained to me in 2016: ‘A corporation had supreme powers of acquisition; more than that it had government finance through 60-year loans – and, as the infrastructure went in, the increase in (land) values generated by development meant all accumulated debt was eventually repaid.’

He couldn’t understand why developers, rather than communities, are now allowed to benefit – ‘they must be rubbing their hands with glee’.

As Lock and Ellis recall, the first generation of 14 new towns proved so successful they became net lenders to other bodies; Harlow, for instance, repaid all its loans within 15 years and started to produce a surplus for the Treasury. But with delivery of the new towns in the hands of a Conservative government in the 1950s, Tory ministers were determined to ensure these profitable new towns did not transfer assets to largely Labour-run local councils when development corporations were wound up.

So the Commission for New Towns (CNT) was born to ensure the Treasury became the beneficiary and, ultimately, to oversee disposal.

Yet after the election of 1964, a Labour government – suspicious of the CNT – displayed a renewed enthusiasm for the new town concept. This reached a peak in 1967-68 with the designation of Milton Keynes, Peterborough and Northampton. And that was almost it.

In short, while the new town story might present a mixed bag of undoubted success and partial failure, the overall initiative surely tells us something more profound. Here was a programme – admirably outlined by Lock and Ellis – driven by ministerial (and civil service) activism. In the early stages, it confronted the ownership of land so that the community could benefit collectively.

And the future? The authors are adamant that, far from being seen as a historical curiosity, legislation underpinning the new town programme has a profound relevance – and potential application – today.

First, they say rising sea levels, driven by climate change, will require planning on a large scale to re-locate communities at risk.

Secondly, they maintain that ex-industrial communities – the so-called ‘left-behind’ places – similarly require a ‘comprehensive planning approach’.

‘In 1946, under much harsher economic conditions (the book was published as the Covid crisis was breaking) , we could have chosen slums instead of new towns, but we didn’t,’ they contend.

New Towns – The Rise, Fall and Rebirth by Katy Lock and Hugh Ellis is published by RIBA Publishing

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37