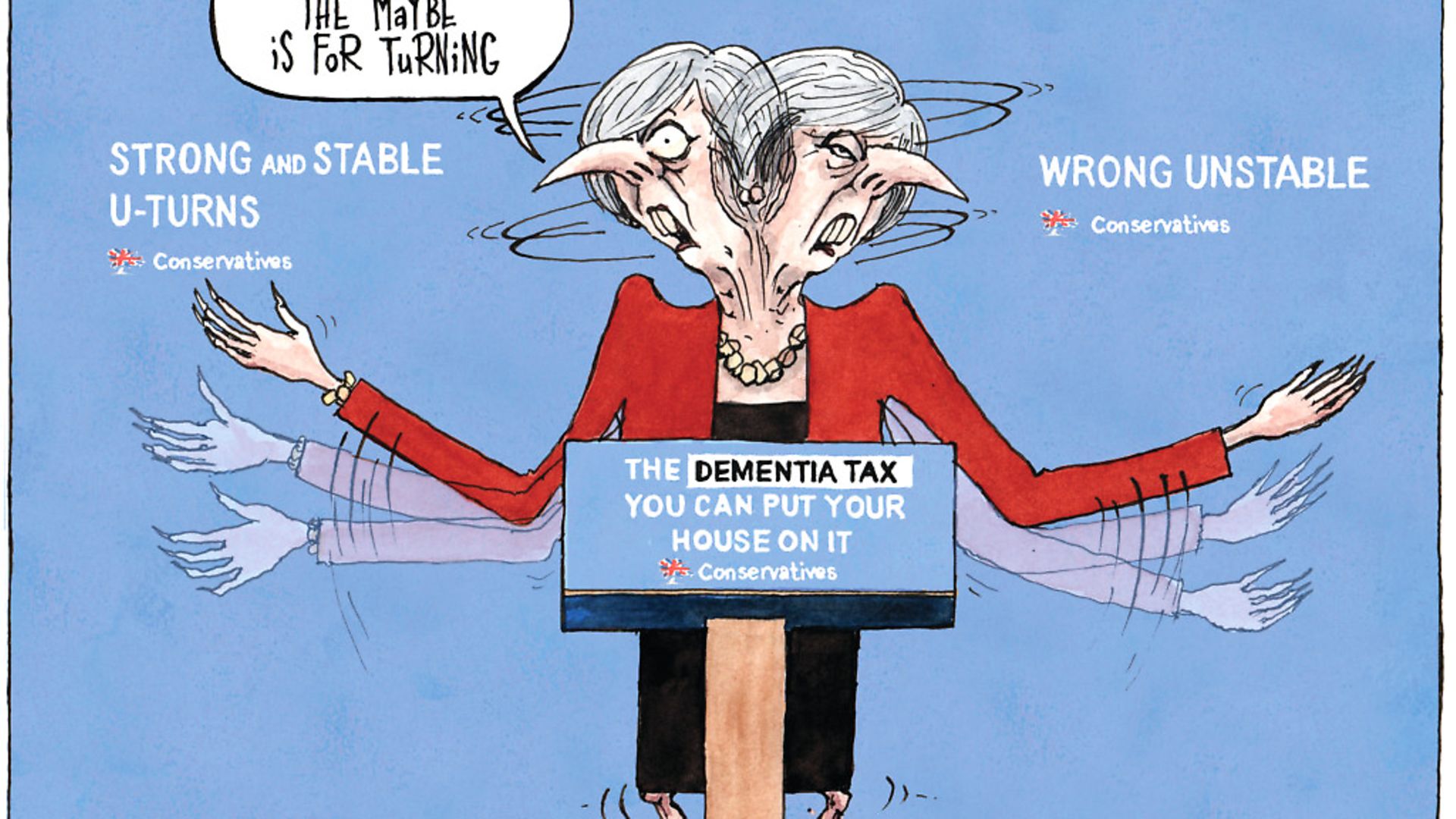

The Conservative’s muddled dementia tax and the subsequent u-turn leave us as far from a humane solution as ever

There is a perception that greedy baby-boomers are responsible for any and every economic ill; that younger generations are suffering while their elders cruise into the sunset on the profits of successive housing booms, their steamer chairs cushioned by generous final-salary pension schemes.

It’s true that some older people are very comfortably off, thank you. Others are in no fit state to go cruising. Or even to walk to the corner shop alone. Hundreds of thousands of them need round-the-clock care to ensure that they don’t harm themselves in a fit of independence – like trying to make themselves a fried egg on toast (having forgotten that they had lunch half an hour ago).

If our cruisers overindulge themselves at the captain’s table to the extent that they become obese and develop type 2 diabetes or have a heart attack, they will be looked after by the rest of society, through the NHS. Likewise if they smoke too many after-dinner cigars and develop lung cancer. Never mind that they were given clear and frequent warnings of the consequences of their lifestyle, they will be looked after and they won’t have to pay.

Not so the chap who might set fire to himself frying an egg. It’s not his fault that he’s ill. He did nothing to bring on his condition, there were no steps he could have taken to avoid it. But he’s not ‘ill’ ill, so he must pay to be looked after. And if he can’t afford to pay now, he (or his more compos mentis relatives) should be comforted by the fact that he won’t be forced out of his home – that will be his family’s fate after his death, when they will be asked to settle the debts, with interest. This is what Theresa May sees as creating a fairer society.

If one partner in a couple living in an £850,000 house gets cancer, they will receive all the treatments and palliative care they need as they see out their days in their own home. They can then leave the property to their children free of inheritance tax.

In May’s ‘fairer’ society, if one partner in a couple living in a £150,000 flat has Alzheimer’s, they should also be able to see out their days at home. But then their offspring will have to surrender up to £50,000 to cover the care bills.

Critics have labelled this a ‘dementia tax’. I’d call it vulture politics. Purists have pointed out that it isn’t strictly a tax: the money isn’t going into a communal pot, it is being used to pay for something required by the person shelling out – like buying knickers at Marks and Sparks, as one FT commentator put it.

Except we can choose whether to buy our knickers from M&S; we can choose to get them somewhere cheaper. If you have dementia, you don’t have choices about how you spend your money. You don’t have choices about anything.

And, too often, nor does your family. Stretched social services departments may offer the ‘care’ that racks up those bills to be settled after death, but in thousands of cases there will be relatives at their wits’ end doing the heavy lifting, unpaid, giving up their own lives to look after shadows of the people they love – who may not even recognise them half the time. Relatives who may very well also be of advancing years, possibly with health problems of their own, who could do with a bit of looking after themselves.

And if they aren’t that old? Working-age daughters (rarely sons) for example? Well, May is offering them the opportunity to forsake their contact with the outside world and take a year off work (unpaid) to look after their Aged Ps, in exchange for a carer’s allowance of sixty-odd quid a week and a probably insurmountable boulder across their career path.

Looking after our elderly is a big issue and it can only get bigger. Successive governments have cut grants to local councils, which are responsible for social services, and the result has been a greater burden on the NHS as people who no longer need to be in hospital are kept in because there is no one to oversee their convalescence at home. Politicians can argue about which budget should be used to pay to care for people who can’t look after themselves, but the fact is there isn’t enough money to go round.

In the 1960s council house jam-jar economy, if there weren’t enough coppers in the milkman’s pot, you’d raid the one for electricity. If robbing Peter to pay Paul didn’t work, you’d have to try to find extra work, or economise and have another day on bread and dripping. The same choices face the state: it can choose to spend more on Peter than Paul, it can cut back, or it can look for a new source of income.

Governments are terrified of raising taxes, especially income tax. Opinion polls may suggest that people would be willing to see the basic rate go up by a penny or two to help the health service or whatever, but no chancellor has dared do so for a generation. Instead the rate has progressively fallen over the past 40 years from 33% when Thatcher came to power in 1979 to 20% today.

This doesn’t mean taxes have fallen. Far from it. It means that chancellors have had to become more inventive in finding ways of raising money.

So where to look when you’re trying to find billions to pay for the care of old people? May is so confident of victory on next month that she is willing to alienate her most reliable constituency: the grey vote.

About 300,000 people who receive care in their own homes would suffer financially from the regime she proposes, a tiny proportion of an electorate of 45 million or so. But the whole reason action is needed now is that those few hundred thousand will become millions very soon. The arch-Conservative Bow Group, which described the proposed measure as the ‘biggest stealth tax in history’, estimates that 70% of elderly people will require some form of care before too long.

Existing rules state that those with more than £23,250 in savings have to pay for their own care costs. If they are in a residential home they may have to forfeit their own property to pay the bill, but if they live in their own home, its value is discounted.

An inquiry under Sir Andrew Dilnot recommended in 2011 that people should contribute to their care costs, but that they should not have to pay more than a total of £35,000. David Cameron agreed to introduce the policy from 2020, but with a higher cap of £72,000.

May threw that idea away and settled for a ‘floor’ rather than a ceiling. Your last £100,000 would be protected – more than four times as much as before – but that sum included the value of your home, even if you were living in it.

At least that was the idea published last week, and reiterated by Jeremy Hunt in a Radio 4 interview in which he stated categorically that the cap was going because it was a bad idea.

Talking of bad ideas, a pensioners’ group described the policy as a ‘Frankenstein’s monster’ of bad ideas bolted together, while Dilnot worried that people would being left alone, helpless and with no control.

After a weekend of uproar, May started screaming variations on ‘fake news’ and ‘project fear’, then showed her strong and stable leadership by saying there would be an ‘absolute limit’ but that ‘nothing had changed’.

Exactly. Nothing has changed. Whatever the cap – she refused to put a figure on it – the idea is still unfair. If we can all chip in to educate our children, to defend our country, to police our streets, is it too much for us all to chip in to look after our old and chronically sick?

May and her team – or those let into the secret, as many ministers apparently weren’t – have been beguiled by the idea of old people sitting on millions of pounds worth of real estate and expecting the state to pay for them to have their bottoms wiped.

It’s perhaps unsurprising that a government might want to tap into that wealth. But it won’t be the only one. With such a vast equity pot there for the grabbing, the sharks will soon be circling. Councils struggling to recruit care workers won’t suddenly find a new pool of staff, but you can bet that agencies will spring up to offer their ‘services’ at suitably high rates (most of which won’t be passed on to the people actually doing the job).

Insurers will start marketing care policies full of caveats, exclusions and get-out clauses at extortionate premiums. And what about equity release schemes? Will they die the death or will there be a scramble to turn bricks and mortar into cash, and spend it before the state gets its hands on it?

The rich will find ways to protect their children’s inheritance – they always do – while unscrupulous financial service providers can be relied upon to dream up new schemes to take money from the less well-off and the less savvy. It will be those who were encouraged to buy their council houses so that ‘wealth’ could ‘trickle down’ through the generations who will end up paying. Indeed, this scheme could well ensure that the ‘wealth’ trickles nowhere but into the pockets of bankers and businessmen.

There will many individual tales of woe. At the moment, no-one can be forced to sell their home to pay care fees if there is someone under 18 or over 60 living there. The Conservative manifesto now says only that the home is safe while the person being cared for or their partner is in residence.

There are many instances of people in their 80s being looked after by relatives in their 50s or 60s. What happens to them when the house has to be sold? Will they suddenly be rendered homeless with a share of £100,000 (they may have siblings wanting their cut) to put a roof over their heads when they are too old to get a job or mortgage?

This isn’t an attack on ‘wealthy pensioners’ but on whole families. As May says, the old people won’t lose their homes. Dutiful middle-aged people who have spent years caring, unpaid, for their parents will.

And what of uncaring relatives? People can do nasty things when large sums of money are at stake. It sounds melodramatic, but it’s not hard to imagine bullying, violence and even the mis-employment of pillows as expectant and exasperated offspring watch their inheritance vanish in a haze of incontinence pads and warmed-up lunches.

Then there’s the other side of that coin: the increased risk of suicide among people who fear becoming a burden on their loved ones without the possibility of being able to pass on the family home as a ‘thank you’ from the grave.

Come on! If you’ve got the money, you should pay your way. There are millions out there who don’t have £100,000. Yes, but there are millions more who do have that sort of money tied up in property. Quite ordinary people who don’t earn very much. They may be healthy now, but they will worry. And if they are astute, they will find ways to beat this scheme. The golden goose will lay few eggs.

Then other ways will need to be found to finance the care required. If dementia isn’t a ‘proper’ illness to be treated via the state, maybe people with other conditions associated with old age will be told that they, too, must cough up. Like a washing machine guarantee, ‘normal wear and tear’ could be excluded: A new hip, knee replacement, cataracts? You’re old, it’s only to be expected. If you have the means to pay, you must. Of course many already do by choice, but we’re entering the realms of buying our healthcare on the never-never and it is the very future generations May is trying to be ‘fair’ to that will have to foot the bill.

The strangest thing about this whole policy is the fact that a much gentler version that would have spread the burden far wider was put forward in 2010 by Labour’s Andy Burnham. His idea was a 10% levy on people’s estates, on top of inheritance tax, specifically to pay for social care. The policy was rejected by his own party as a vote loser – but still used as propaganda by the Tories, who produced a gravestone poster to hammer Gordon Brown.

If the Burnham scheme were introduced today, the total bill – including inheritance tax – for the estate for a single person living in a £500,000 house would be a maximum of £145,000. Under the May plan, the maximum would be £400,000. Depending, of course, on where she sets that ‘absolute limit’. And, of course, the higher that limit, the more the wealthy will benefit.

Mocking the Burnham proposals seven years ago, a Daily Mail article complained that it was ‘grotesquely unfair’ that people who worked hard all their lives would suffer while those who spent a lifetime on benefits and not saved to buy their own home would pay nothing.

Last week it endorsed May’s plan, praising her ethical, moral tone and her honesty. The other Right-leaning papers also accepted the idea as sensible. Times change, needs must. But would they have been so sanguine had the idea come from Jeremy Corbyn?

Bemoaning the fact that Britain’s ‘hard-pressed’ middle classes would again be left to pick up the bill, that 2010 Mail article asked why on earth taxes like National Insurance couldn’t cover the cost.

Quite. It doesn’t have to be income tax or national insurance, though it could be. It could be a different, more evenly-spread, kind of wealth or inheritance tax. But why should those unlucky enough to need this particular sort of care be the only members of society that society won’t look after?

Liz Gerard worked on national newspapers for 40 years. She now blogs on Fleet Street at www.sub-scribe.co.uk

HOW THE PRESS REACTED

After Brexit, there are two subjects that really matter to the Daily Express: pensions and Alzheimer’s. It might be thought, therefore, that the paper would be upset, angry or even outraged by the Tory manifesto with its ending of the triple-lock on pensions, means-testing of the winter fuel allowance and new plans for social care funding.

Except that now that there is no prospect of Nigel Farage ever running the country, nothing must be allowed to stand in the way of May’s re-election.

Until this week, the Sun and the Mail had both felt emboldened by the prospect of a landslide to question various Tory policies – although neither was sufficiently confident to put the dementia tax U-turn, the biggest story of the election so far, on their front pages.

The Express has skirted uncomfortable issues from the start. It declined, for example, to report Corbyn’s plans to end hospital car parking charges – even though it had run a ‘crusade’ against them itself.

The social care initiative was fanfared by the paper as ‘May’s plan for a fairer Britain’ and the next day’s follow-up was a single-column story headlined ‘PM blasts critics…’ It did find a home for the U-turn on the front: ‘Mrs May listens to concerns…’

Everything must be given the best possible gloss.

The paper may like to protect its readers from unpalatable truths, but the people running it cannot be unaware of the impact these policies will have on its core readership. And so, on Saturday, it produced possibly the most cynical front page of the campaign so far. Its main headline: ‘Alzheimer’s cure hope.’

Some German researchers have looked at a protein associated with Alzheimer’s in a test-tube. They don’t know yet know if what happened in that test-tube replicates what happens in the brain. That headline was irresponsible. But was it more than that? Was the Express being cynical or am I?

For I suspect that when executives realised what that manifesto pledge meant – forget your worries about inheritance tax, if you have dementia, we’ll bleed our children nearly dry – the order went out for the health reporters to ‘find’ an advance in Alzheimer’s research.

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37