CHARLIE CONNELLY tells the story of Tamara de Lempicka – a much-travelled artist who thrived on transition.

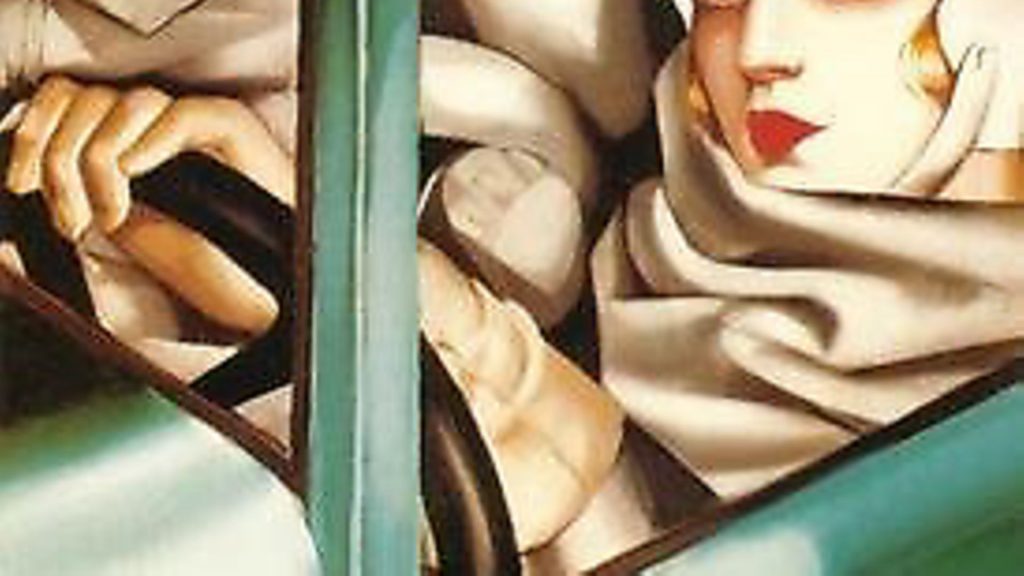

Not many single images can justifiably claim to define an entire era but Autoportrait (Tamara in a Green Bugatti) by Tamara de Lempicka comes as close as any.

Commissioned in 1929 for the cover of Die Dame, a German feminist magazine, the self-portrait in oil on board shows the artist tightly framed at the wheel of the car wearing a close-fitting beige leather driving helmet strapped under her chin and long matching gauntlets, her left hand resting lightly on top of the steering wheel. The bright red of her lipstick between the beige of her outfit and the muted green of the chassis draws the viewer to her face, then up to her eyes.

While there’s almost a sleepiness to the lids the steely gaze from beneath, looking just past the viewer, evokes a heady mix of determination and insouciance. The painting somehow manages to depict speed and utter stillness at the same time with an added sprinkling of menace, as if this is the last thing you would see as she ran you over. It’s a self-portrait that speaks of independence, liberation and wealth. It is the 1920s in a single image; the personification of the jazz age, the soul of art deco. It’s not the car that’s running you over and leaving you for dead, it’s the times themselves.

There is a great deal packed into this one small painting: it is also the absolute distillation of Tamara de Lempicka, who found herself at the heart of some of 20th century Europe’s most tumultuous events and produced work displaying the tangible legacy of centuries of European art made utterly modern. In her life as much as her painting she was always at the cutting edge of Europe itself.

She was still in her teens and living in St Petersburg when the Bolshevik revolution of 1917 kicked out the old order and set Russia on the path to Soviet communism. Even by then she’d seen a great deal of the continent and experienced much of its cultural life. Born in Warsaw to a lawyer father and a socialite mother – they’d met at an exclusive spa in the south of France – Tamara Gurwik-Górska was sent to a boarding school in Lausanne that she hated from the start and soon feigned illness to escape. She was dispatched to her grandmother who immediately took her on an extensive tour of Italy, exploring the great art galleries where Tamara developed a love for the Renaissance portraiture that would influence her subsequent career with impressive single-mindedness..

When not roaming Italy with her grandmother she would stay with an aunt in St Petersburg where in 1911, still in her early teens, Tamara attended a fancy dress ball given by her aunt’s wealthy banker husband. She dressed as a Polish peasant girl with a goose on a lead, an ensemble that turned the head of Tadeusz ?empicki, a lawyer and at the time one of St Petersburg’s highest society bachelors. They married in 1916, a year before the Russian revolution that would, in effect, define the course of her life.

One night in 1918 there was a hammering on the door and Tamara, by then the mother of a baby girl, Kizette, was forced to watch as the Cheka, the Bolshevik secret police, burst into their home, pulled Tadeusz from his bed and bundled him out into the darkness. It took weeks for Tamara to even find where her husband was being held, let alone employ the assistance of diplomats to secure his release. Realising they were no longer safe in the city the couple fled with their daughter, first to Copenhagen, then on to Paris where they found other bewildered family members similarly displaced.

At the prompting of her sister, Tamara, set about transforming herself into a portraitist. She enrolled at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière where her extensive knowledge of Italian art was gradually honed into a distinctive style of her own that borrowed from the Cubism of André Lhote and the early work of Picasso.

‘My aim,’ she wrote, ‘was never to copy, but to create a new style, bright, luminous colours and to scent out elegance in my models.’

She made her name by exhibiting at the 1922 Salon d’Automne in Paris, where she added the more francophone ‘de’ prefix to her married name, and three years later exhibited her work at two venues during the Paris Exposition internationale des arts décoratifs et industriels modernes (International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts), the expo that gave the world the term ‘art deco’. Also in 1925 she staged her first solo show in Milan for which she worked frantically, producing 28 pictures in just six months.

‘There are no miracles,’ she said of the work ethic that characterised her career, ‘there is only what you make.’

Once finished in the studio she would reward herself with, ‘champagne, a bath and a massage’, the latter often coming from the subject of whatever portrait she was working on that day, male or female. Tadeusz was eventually left behind as de Lempicka joined the coterie of the European avant-garde and embraced the burgeoning freedom of the Parisian 1920s by exploring her sexuality as deeply as she explored the form of portraiture. She was a regular at the American writer Natalie Barney’s lesbian salons, shared lines of cocaine with André Gide, mixed with Vita Sackville-West and Colette and had a serious relationship with the nightclub singer Suzy Solidor, the subject of one of her best portaits.

Shortly before she produced Autoportrait de Lempicka gained the patronage of a doctor called Pierre Boucard and his wife. Hugely wealthy thanks to an indigestion remedy he’d devised, Boucard was already a collector of her work and the generous stipend he provided gave the artist enough financial stability to buy and refurbish a large house on the Left Bank.

In the early 1930s de Lempicka was commissioned by a Habsburg baron named Raoul Kuffner to paint his lover, a dancer from Andalusia called Nana de Herrera. The portrait was not a flattering one, and served its purpose in that the baron broke off his affair with de Herrera in favour of its artist shortly afterwards. When Kuffner’s wife died soon afterwards the couple married in 1934. If the 1920s had been about freedom and the dismantling of sexual barriers, the following decade saw authoritarianism on the rise. Paris was shielded from it until the German invasion of 1940 but de Lempicka was unsettled by a column of Hitler Youth cadets belting out marching songs as they filed past the Austrian hotel where she and her husband were on holiday in 1938. Of part-Jewish heritage, de Lempicka convinced her husband to sell his Hungarian estates and relocate the couple first to Los Angeles, then New York, where she found her particular brand of abstract expressionism hard to place. America just didn’t understand her, more impressed by the Fifth Avenue duplex home and aristocratic title she had taken on her marriage than her work. Where Europeans had feted her art and treated her as a great cultural figure, for New Yorkers she was an aristocrat who did a bit of painting on the side.

De Lempicka had settled in a stable America but she only really thrived on transition. She epitomised the period between the Russian revolution and the rise of Nazism, a time when Europe was a tumultuous hotchpotch culturally, socially and artistically and suited her art and lifestyle perfectly. She reached into the past to make a new future but in America there was no past to find.

For the New York Times on her death in 1980 she was the ‘steely-eyed goddess of the machine age’, a woman of varied and voracious appetites who suited so perfectly the era in which she’d thrived her self-portrait came to embody it. ‘Light by Caravaggio,’ said one European critic about Autoportrait, ‘lipstick by Chanel’.

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37