As Terry Gilliam’s version of Don Quixote finally reaches our screens, after 30 years in the pipeline, Richard Luck looks at what makes the book so… quixotic

In the land of the unmade movie, Terry Gilliam is king. Leaving aside the pictures he’s turned down – Who Framed Roger Rabbit, Forrest Gump, The Truman Show – the former Python’s raft of unrealised projects is in equal parts long, tantalising and frustrating.

Watchmen, A Scanner Darkly, The Defective Detective, A Tale of Two Cities, Theseus and the Minotaur, Good Omens, A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court – Terry Vance Gilliam has sought to bring all of the aforementioned to the big screen.

As you might notice, some of these projects have been realised by others. However, those familiar with Gilliam’s unique cinematic vision might agree that, as excellent as HBO’s Watchmen and Amazon’s Good Omens undeniably are, we’re poorer for being denied the opportunity to see the director of Brazil and 12 Monkeys translate these literary masterpieces.

And then there’s Don Quixote. Or rather, The Man Who Killed Don Quixote, an ambitious blend of Cervantes with Mark Twain’s Connecticut Yankee that Gilliam has been working on for the better part of 30 years, and which is finally released in the UK this week.

When he first tried to set up the picture in 1989, he was significantly hampered by the fact that his most recent movie, 1988’s The Adventures of Baron Munchausen, was among the biggest flops in the history of film.

All the same, the good people at Phoenix Pictures signed a deal to make Don Quixote with Gilliam. With Sean Connery and Nigel Hawthorne in contention for the title role and Danny DeVito practically born to essay the Don’s dumpy right-hand man Sancho Panza, things looked good right up until the director decided he didn’t have enough money to realise his vision. Phoenix tried to soldier on with the Australian film director Fred Schepisi and a Quixote-Panza double-act of John Cleese and Robin Williams but to no avail. Don Quixote was officially cancelled in 1997, to the disappointment of many but the surprise of few.

Such are the vagaries of the movie industry that, the very moment Phoenix’s Quixote flamed out, Terry Gilliam became a very hot director. His first post-Munchausen movie, 1991’s The Fisher King, had been a big critical and commercial success.

Likewise 1995’s 12 Monkeys demonstrated that there was a significant appetite for Gilliam’s idiosyncratic cinema. And with 1997’s Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas proving that he could adapt the seemingly unadaptable, Terry and his Fear And Loathing co-writer Tony Grisoni geared up for a fresh tilt at Quixote.

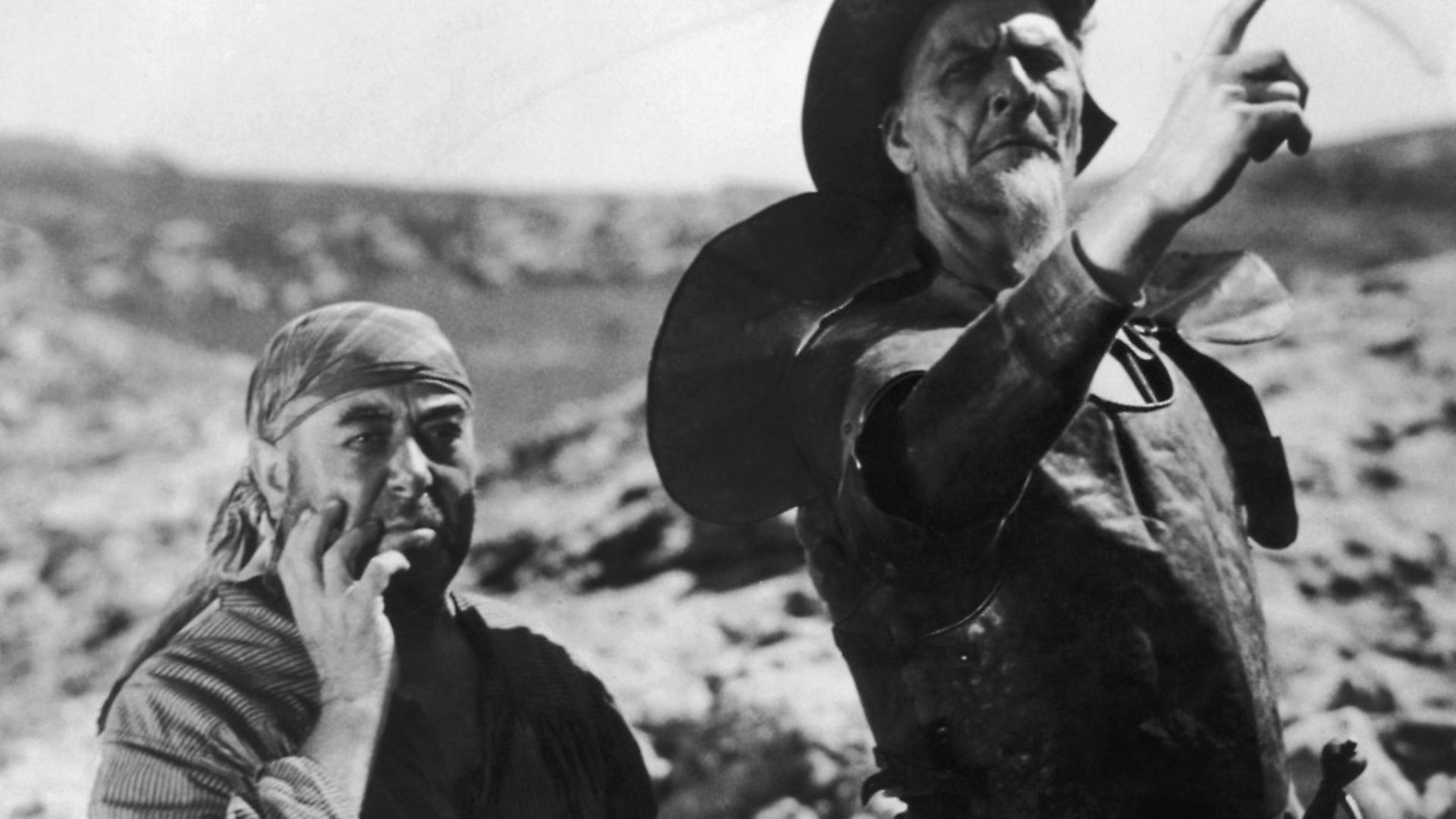

The decade Gilliam had already invested in his picture was as nothing compared to the 28 years Orson Welles dedicated to his Quixote adaptation. Shooting his first reels in 1957, Welles still hadn’t completed his Don by the time of his death in 1985.

Long before his passing, the great director bid ‘adios’ to both his Quixote and his Sancho Panza, Francisco Reiguera and Akim Tamiroff dying in 1969 and 1972 respectively.

Contrary to popular belief, the time Welles took over his Quixote movie had less to do with a lack of funds than with a desire to fashion a film the way an author might write a novel.

As such, it’s not surprising that the creator of Citizen Kane took against those who pestered him about when, if ever, the picture would be finished, so much so that he toyed with renaming the movie When is Don Quixote Coming Out? The answer to this question would be 1992, when the Italian director Jess Franco cobbled together a cut of Welles’ film, albeit one that – according to those who knew Orson – bore very little resemblance to the picture the big man set out to make.

It’s better than many a cinematic version of Quixote, mind you.

Ever since the earliest days of silent film, people have been trying to translate Cervantes’ creation, most with little or no success. Even true masters of film such as GW Pabst (1933) and Grigoriy Kozintsev (1957) have been defeated by the Don – succeeding in getting their versions onto the screen, but failing to the story much justice.

One might venture than any movie adaptation of Don Quixote is bound to fail. At well over 800 pages in length, paring the tale down to around two hours is like trying to fit an elephant into a Renault Espace. It also doesn’t help that so much of Quixote consists of the knight and his squire telling one another bizarre shaggy dog stories.

That said, since these campfire tales are largely extraneous to the plot, you might also think that it would be easy to jettison them, together with the tome’s various songs and poems.

However, to remove all this material from the plot is to deny the essence of the novel. Rather like the meandering observations in Sterne’s Tristram Shandy, the seemingly pointless parts of Quixote are, in truth, the whole point of the novel. Oh yes, and the ending’s a real downer.

With the novel an adaptor’s nightmare, it’s understandable that many of the best received Quixote adaptations draw not upon the book but the 1965 musical Man of La Mancha. But while it might be packed with cracking Mitch Leigh/Joe Darion compositions like The Impossible Dream, even Dale Wasserman’s stage version is capable of striking a bum note. Just ask Kelsey Grammer whose recent West End revival of La Mancha opened and closed in the time it would have taken Dr Frasier Crane to fly from Boston to Seattle.

Perhaps it was the chequered history of Quixote adaptations that encouraged Gilliam and Grisoni to adopt a new approach to the tale. As initially conceived, The Man Who Killed Don Quixote was the story of an advertising executive who finds himself sucked through time – not to mention, the thin line between fact and fiction – to the days of Cervantes’ hero. With a budget in excess of $30 million sourced entirely from Europe – no danger of Hollywood interference this time around – Gilliam had secured the services of his Fear and Loathing leading man Johnny Depp, together with Depp’s then partner Vanessa Paradis, Smack the Pony’s Sally Phillips and a pre-Who Christopher Eccleston. As for the pivotal role of Quixote, the director handed that to the French actor Jean Rochefort, who was such a good fit for the role Cervantes might have cast him himself. What happened next will be familiar to anyone who’s seen Lost in La Mancha, the harrowing but utterly fascinating 2002 documentary about the disaster-ravaged Quixote shoot, in September 2000. Flash floods, unrehearsed extras, a Don with a chronic back condition, a budget that’s barely half as big as it needs to be, an uncooperative horse… these were just some of the issues that lead to The Man Who Killed Don Quixote coming apart within the first week of filming. It says a lot for Terry Gilliam that he allowed filmmakers Louis Pepe and Keith Fulton to complete their documentary. Then again, since the pair had done such a fair-minded job on The Hamster Factor – their 12 Monkeys making-of film – Gilliam’s insistence that “someone has to get a film out of [The Man Who Killed Don Quixote]” is both as understandable as it is laudable.

“The thing is, I’ve never made the films I’ve wanted to make.” So said Gilliam in 1997, pointing to key scenes in both Brazil and Baron Munchausen that he had to scrap because the budget wouldn’t accommodate them. Swallowing such changes might suggest that Gilliam has a mature attitude towards compromise. The truth of the matter is, Terry has a stubborn streak a mile wide. Because of this, Quixote was never Don and dusted, at least not in his eyes.

For Gilliam, it was a case of busying himself while the insurers pondered whether to hang on to the rights to his Quixote screenplay. So it came to pass that Terry directed operas for the Italian stage and made The Brothers Grimm (2005) for Harvey Weinstein. Naturally, few things went our man’s way during the Quixote hiatus. Weinstein wrung much that was good out of Grimm, Tideland (also 2005) struggled to find an audience, and The Imaginarium Of Dr Parnassus (2009) suffered the worst disaster that can affect any film when leading man Heath Ledger passed away mid-way through production.

And still Gilliam sought to resurrect The Man Who Killed Don Quixote! “Everything I’ve done since [the cancellation] has been because I couldn’t get Quixote made,” he’d explained in 2006.

By then, the rights to the Quixote screenplay were back in his and Tony Grisoni’s possession. Ever gentlemen to make lemonade when presented with lemons, the pair seized upon the previous collapse as a positive, claiming that the script had certain problems that needed to be ironed out. With the screenplay retooled, a new version of the film could have been in cinemas by the decade’s end.

Jean Rochefort’s health had worsened and Johnny Depp had become the biggest star on the planet thanks to the Pirates of the Caribbean pictures so the director recast Robert Duvall as the Don (after initial discussions with fellow Python Michael Palin) and Ewan McGregor as the ad exec. At which point, the funding collapsed and the whole thing acquired a very familiar ring.

If only the writers had heeded the words of Miguel de Cervantes, who included a curse within the text of Don Quixote that doomed all those who saw fit to interfere with the author’s creation.

From what you’ve learned of the man so far, you might not be surprised to hear that Gilliam considers all talk of a hex to be “bulls**t”. And so it has proved to be for, after completing 2013’s The Zero Theorem, he again rallied the troops and finally got The Man Who Killed Don Quixote in the can.

Okay, so the production didn’t wrap until June 2017, and its premiere at the 2018 Cannes Film Festival was nearly scuppered by the same copyright issue that held up Quixote’s UK release. And it goes without saying that Gilliam had to cast new leading men, although in a rare instance of good fortune, he was able to secure the services of regular collaborator Jonathan Pryce (Brazil, Baron Munchausen, Brothers Grimm) and then recent Star Wars recruit Adam Driver as the Don and Toby respectively. Terry also retained the services of Nicola Pecorini, the Italian cinematographer who’s been his DP of choice since Fear and Loathing. And – would you credit it? – after all these years and all those line-up changes, Gilliam has wound up making his best film since his Hunter Thompson adaptation.

Naturally, this being a Gilliam film, it won’t be for everyone – even his most accessible films (principally 1981’s Time Bandits) have an uncanny ability to befuddle. But the performances are universally excellent, the film looks a million dollars, the script is challenging and funny, and there’s space a-plenty for all his favourite things, from the power of myth and the importance of dreams to the obligatory dwarfs and giants.

A man whose singular approach to filmmaking has left him on the outs in Hollywood, Gilliam’s willingness to speak and think for himself has upset a lot of people of late. While there’s no denying that some of his comments have been crass and many of his arguments unlettered, it’s worth remembering that Gilliam isn’t who you might assume he is. For example, when people bang on about the advantages the Pythons’ Oxbridge upbringing afforded them, you can’t blame Gilliam for arching up, what with him being a native of Minneapolis, Minnesota, whose education included a stint in the National Guard and aeons writing and drawing for US underground magazines.

No, he was no son of privilege. He’s also someone who renounced their US citizenship in the wake of the second Gulf War, so exasperated was he with the presidency of George W. Bush. Terry Gilliam is hard to pin down and impossible to predict. As such, controversial, even wrongheaded opinions are as likely as words of great empathy and wisdom. Likewise, these qualities are the key to Gilliam’s filmmaking. For in a business where even the likes of Michael Bay are labelled visionaries, Terry’s is a truly unique vision. As Don Quixote proves, it can just take a while to come into focus.

The Man Who Killed Don Quixote is released in UK cinemas on January 31

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37