By choosing to focus his work on his mother, Edouard Vuillard found something that had escaped other artists. Florence Hallett reports on a quietly revolutionary painter

Madame Vuillard sits in front of a mirrored wardrobe – an armoire – her arms wrapped awkwardly about her as she arranges her hair. In fact, she is engaged in such concentrated contortions that the painting almost seems a caricature, a man’s baffled response to a mysterious, feminine ritual.

It’s a picture that nods with some humour to the timeworn tradition of men painting women bathing, or attending to their appearance, Madame Vuillard’s stout figure and gnarled, arthritic hands setting her apart from the idealised beauties typical of these usually erotic images. And yet Vuillard’s painting is not disparaging, or mocking: this is a familiar, fond portrayal of the artist’s mother.

The French post-Impressionist painter Édouard Vuillard (1868-1940) made no fewer than 500 paintings and pastels of his mother, and many more prints, drawings and photographs.

Madame Marie Vuillard had been widowed relatively young, in her forties, and lived with her son and other family members in a series of Paris apartments until her death in 1928 aged 89, when Vuillard was 61. An exhibition at the Barber Institute of Fine Arts, Birmingham, brings together a selection of these works, and is the first to look exclusively at the artist’s depiction of his mother, who he called his muse.

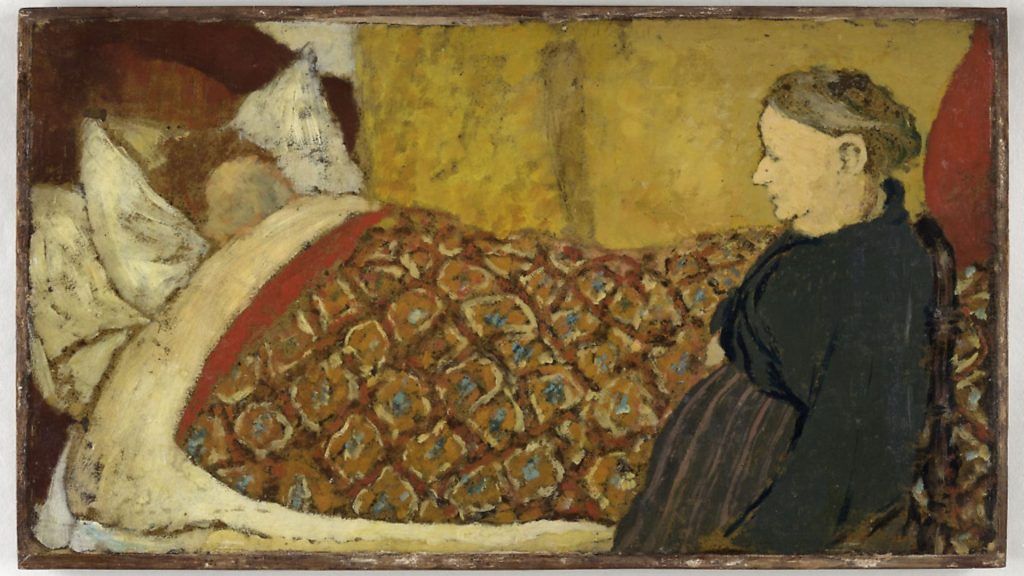

In the confined space of their apartment, Vuillard and his mother lived and worked together, his mother running a busy dressmaking atelier while her son painted from his bedroom-studio. Their shared lives are reflected in his endlessly varied depictions of her, in which she is shown as a mother and a daughter, doing housework, working as a seamstress, sleeping or reading.

Caring for her sick, pregnant daughter Marie, she is an embodiment of idealised maternal love; elsewhere she is a gruff, redoubtable figure, at times exerting a formidable presence, more felt than seen.

As a professional woman she is seen absorbed in her work, attending to her clients or busily directing her daughter and apprentices. But in all their shades of mood and emphasis, their heartfelt interest in exploring the breadth and depth of female experience is strikingly unusual.

Though he produced portraits, landscapes, stage designs and large-scale decorative panels, Vuillard is best known for these small-scale depictions of domestic life, which not only reflect his preoccupations as a painter, but provided him with a context in which to test his most innovative ideas.

Pictures from the 1890s, made at the very beginning of his career, reflect his association with the Nabis, a group of art students who took their name from the Hebrew word for ‘prophets’.

As ardent followers of Paul Gauguin they pursued the Impressionists’ emphasis on light and colour, but rejected naturalism in favour of a decorative aesthetic.

Expanses of colour combine with flattened perspective to emphasise the painted surface, with emotion mediated through colour and composition. Paintings like The Lunch (1902), with its daring use of red on red, are testament to Vuillard’s avant-garde credentials, anticipating the bold experiments in colour conducted by Matisse and the Fauves – the wild beasts – some years later.

In his atmospheric painting Interior with Seated Figure (1893) light and shade, colour and pattern delineate not just the actual, physical space of the Vuillards’ apartment but the character of its occupation. His sister Marie is seated before us, and almost continuous with the room, her dark dress absorbed into the wall-covering behind her, while in the sunlit room beyond his mother is busy at some domestic duty.

Through light and shade, the painting establishes a hierarchy: though Marie appears to be the subject of the painting, sitting still, and quiet as she poses for her brother, it is the restless, bustling presence of their mother in the adjoining room that dominates the scene.

The painting’s pleasingly decorative surface is typical of Vuillard’s work from the 1890s and early 1900s, its structure articulated in pattern, colour and texture. This is how Vuillard and the Nabis railed against academic tradition, rejecting the modelling of forms in light and shade that had been standard practice for artists since the Renaissance.

Objects and figures achieve an equivalence in Vuillard’s hands: in Madame Vuillard arranging her Hair (1900) the figure of the artist’s mother is described as an expanse of patterned fabric, so that she seems no less permanent a fixture than the armoire which appears time and again in these pictures; equally, pieces of furniture are rendered as characterful and alive as she.

Living among dressmakers, Vuillard’s interest in pattern seems a consequence of the many coloured and textured fabrics that were part of his daily experience. A tiny, jewel-like painting, Two seamstresses in the Workroom (1893) is beautifully vivid, like swathes of richly coloured fabric jumbled together as if strewn across a worktable. But this is no confection – Vuillard’s paintings reward close, slow looking, and it takes time for the figures of the seamstresses to emerge, with a third, partially hidden figure, thought to be Madame Vuillard herself, revealing itself at the picture’s far left.

Absorbed in their work, their faces cast in shadow, these are Madame Vuillard’s young apprentices, working after dark in the orange glare of artificial light. Made in the year after legislation was passed in France to regulate the working hours of women and children, the painting hints at Vuillard’s interest in contemporary politics and social issues. Children under 13 were no longer allowed to work at all, and women’s hours were limited, though family businesses such as Madame Vuillard’s were exempt from these new rules.

Vuillard’s attention to women’s work was not in itself novel, and mothers tending to children, or servants and peasant women doing housework were popular subjects for Dutch and French painters of the 17th and 18th centuries. Vuillard’s contemporaries painted women in the home, too, but as Dr Francesca Berry, curator of the Barber exhibition points out, none of these precedents can claim Vuillard’s insight. ‘Vuillard’s work drills down into a feminine experience much more profoundly’, she says. ‘And it’s also interesting because it’s a petit-bourgeois – lower middle class – not an upper middle class vision of domestic life. Vuillard is unusual because you get professional work being portrayed in domestic space – it’s not just about servants working.’

For Berry, this makes him singular. ‘One of the reasons I like him is because he’s interested in the feminine, but not just from an erotic point of view which is what most male modern artists want to deal with.’

Vuillard’s interest in the feminine, and specifically his devotion to his mother, doesn’t sit well, either with entrenched notions of manliness, or of the artistic persona, says Berry. ‘There’s a long history of trying to effeminise him’, she says. ‘A question I am commonly asked is, ‘Was he gay?’ There’s a flawed assumption – rooted in stereotypical thinking on masculinity – that if he was gay the maternal focus can be explained away, and that if he wasn’t gay, there must have been something unusual about him, or that he was a reclusive person.’

If his depictions of closed domestic space have seen Vuillard characterised as an almost unworldly figure, removed from the cut and thrust of life at large, Berry explains that this could hardly be further from the truth. ‘He wasn’t reclusive at all, but that’s the way his art’s been written about. What I want to do with this exhibition is to say that this is very socially engaged painting, it’s politically engaged, and he explores very current issues about women’s work. He’s right in the heart of Paris and he was out a lot and also ran an avant-garde theatre. He was a regular on the Montmartre, vanguard scene of the 1890s, then as he became more successful he mixed with princes and the cultural elite. He was extremely sociable, but he came back to his home and his mother.’

For all his interest in expanding the representation of women beyond certain formulaic types, their activities peripheral and ultimately separate from male experience, Vuillard’s attitude to women probably does not count as progressive, though at times it is certainly ambiguous. The title of his 1899 lithograph The Cook, is intriguing. It is hard to guess his tone as he refers to his mother as a domestic servant – is it meant as a bald statement of fact, or might it be wry, rather like those car stickers that read ‘Dad’s Taxi’? Certainly all the evidence of Vuillard’s paintings makes it hard to believe that he meant it in a derogatory way, not least because Madame Vuillard fulfilled so many functions, functions that he chose to address and promote in his work.

In 1920, as he was about to catch a train, Vuillard said to his biographer Jacques Salomon, ‘Maman is my muse.’ Salomon felt himself in receipt of a precious and closely-held secret, that the key to understanding Vuillard’s painting was to recognise his love for his mother. And yet this exhibition reveals that Madame Vuillard provided so much more than a model of maternal perfection, to be revered and idealised in the way that artists had done so well before him. Instead she provided a model of contemporary womanhood, through which he could explore the domestic realm in a truly modern way.

Maman: Vuillard & Madame Vuillard runs at the Barber Institute of Fine Arts, University of Birmingham, until January 20, 2019; for more information, visit barber.org.uk

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37