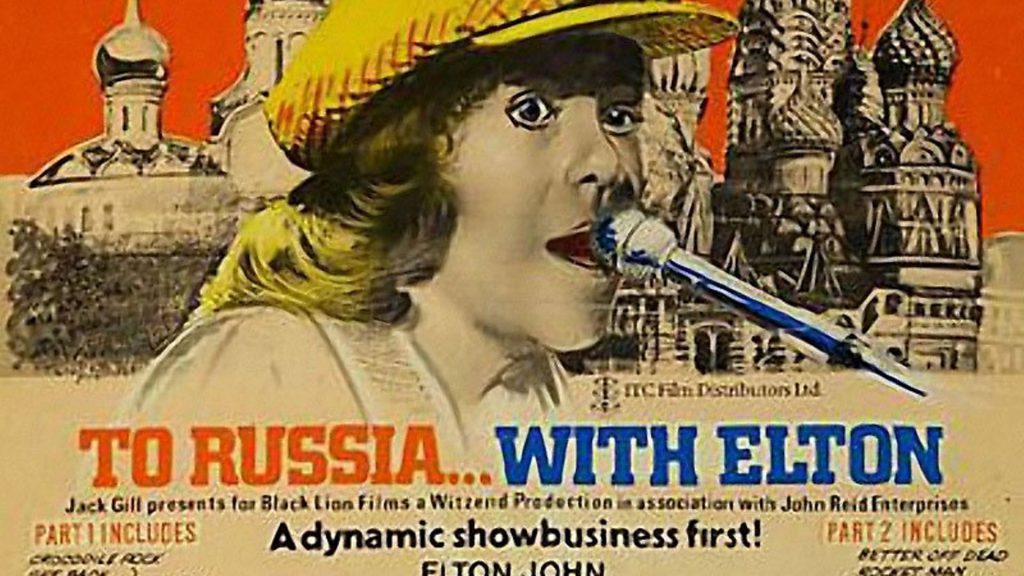

Forty years ago this month, the Rocketman began a tour of the USSR. Both the country and his career were ailing. Only one would survive. RICHARD LUCK reports on a remarkable chapter in musical history.

In early 1979 Elton John was lunching with his manager, and former lover, John Reid and the concert promoter Harvey Goldsmith. The trio were reflecting on the singer-songwriter’s extraordinary decade.

All but unknown at the start of the 1970s, John had topped the US album charts on six occasions, had had three chart-topping LPs in the UK, six Billboard No.1s, and toured extensively on both sides of the Atlantic.

Keen to find new challenges for their charge, Reid and Goldsmith asked John whether there was anything in particular he wanted to do next. The singer was most determined about what he didn’t want to do. “I’m not touring,” he insisted. He was clearly bored by the prospect of re-visiting familiar territories.

As Goldsmith later recalled: “He kept saying, ‘I’m not touring, I’m not going to all those places I normally go’.” But with so much of the globe thus ruled out, John did have one idea that surprised his dining guests. “What about Russia?” the Piano Man mooted.

So, once lunch was over, Goldsmith set about writing a letter to the Soviet embassy. You can only guess at the missive’s exact contents but when it arrived on the desk of an official at the Kensington Palace Gardens address, the proposal it contained was evidently an attractive one.

In the best traditions of the Cold War, the Soviets made their discrete approach in one of Britain’s great university towns. On the evening of April 17, 1979, backstage at Oxford’s New Theatre, where he just performed, John was introduced to Vladimir Kokonin, deputy director of the Russian state music promoter, Gosconcert. Goldsmith’s letter to the Russians had ended up with Kokonin, who had travelled to Britain with a deal to make.

With the Moscow Olympics only a year away, the Soviets were looking for opportunities to show outsiders that there was more to their country than long queues, food shortages and the annual May Day parade. It was also a chance to appease – in safe, controlled circumstances – a growing interest in western culture among the Russian people. A proposed tour by Elton John, therefore, could help the Soviets improve external and internal relations.

As he made his pitch, Kokonin told John how much he had enjoyed the gig and expressed his enthusiasm for the unthreatening nature of his music. As discussions went on, plans for a visit to the USSR began to take shape.

In truth, it may not have just been fatigue with familiar places that led John to look beyond the Iron Curtain in 1979. A Russian tour also offered him the chance of a much-needed publicity coup. The second half of the 1970s had yielded fewer hit singles than the first and a series of underperforming albums.

Meanwhile, the emergence of punk made John seem, at best, impossibly safe (an attraction for the Soviets, of course), at worst, decidedly old hat. Added to this was a less-than-successful hair transplant and an anxiety-related health scare – all factors that meant that, as the decade drew to a close, John’s career was almost – if not quite – as ailing as the Soviet Union itself. Just as the Russians wanted the tour to play to two audiences – both at home and abroad – so did John.

With so much riding on the trip – both for the Soviets and the singer – it was with a great sense of occasion that, at Heathrow Airport on May 20, John and his entourage boarded an Aeroflot flight bound for Moscow. (Their stage and sound equipment had already left on a truck journey across Europe to Leningrad, location of the tour’s first four shows.) Those with him on his great adventure included Reid, Goldsmith, his percussionist Ray Cooper and John’s mother and stepfather, Sheila and Fred Fairbrother. Also on board were the sitcom writers Ian La Frenais and Dick Clement, who had been recruited to try their hand in the less familiar field of documentary film-making.

Alas, the touring group’s itinerary went for a burton the moment they had completed the complex border checks at Sheremetyevo Airport. Unwilling to let their guests fly to Leningrad (the official explanation was unclear; possibly just good old fashioned Soviet paranoia), the tour party were instead obliged to travel via night train, on the eight-and-a-half hour ‘Red Arrow’ service. “We presumed there was something they didn’t want us to see,” the singer later mused.

The Soviets had assigned a minder to the group, a young man called Sacha who had an aversion to smiling and an impressive line in hard stares. The party drew lots to decide who’d ask their companion whether he was in the KGB, then thought better of it.

Sacha was the first sign that touring in the Soviet Union was going to be different to elsewhere John had played. Others soon followed. During his first performance, at Leningrad’s Oktyabrsky Hall, the singer noticed that at the end of each song, there was little in the way of applause and even less in the way of cheering.

He quickly surmised that the reason for such restraint had something to do with the intimidating presence of several official-looking chaps milling about the auditorium. And those filling the front few rows weren’t going to give in to mad abandon, what with them all holding top military and political positions.

Despite the fact that none of John’s records were for sale in the country – something which stunned the singer upon discovery – demand for concert tickets had been high. The price had been set at eight roubles, twice the average weekly wage in the Soviet Union, and more than 90% of them had been taken by senior Party members, diplomats and military officers.

However, when the houselights went up after his last number, Crazy Water, several of these officials headed out of the hall. When John returned to the stage for his encore, therefore, there was a somewhat more relaxed vibe among the remaining audience. Several fans began advancing towards the stage from their seats at the back, with some singing along and even giving peace signs to the onlooking security staff, as John belted out, among others, Back in the USSR.

Robert Hilburn of the Los Angeles Times was among those present. He later recalled: “I was watching the official guests’ faces. And there was that registering of, ‘Why is this all going on?’ And you see this dawning, and this expression and so forth, and it’s a dangerous thing, it’s a real powerful force.”

After the concert, the younger members of the audience took the party outside, gathering in front of the venue, chanting John’s name until he appeared in the dressing room window.

The significance of the evening was not lost on journalists accompanying the tour. The Daily Telegraph reported “Elton John Stuns Soviet Rock Fans”, while the New York Times said that “policemen and other Soviet officials were helpless” in their efforts to control the crowd.

It was also not lost on the communist authorities. As the Times put it, officials saw it “like a sort of slight weakening, a sort of concession to Western culture”, and requested that the show be toned down a bit. In his dressing room after the concert, John was asked to refrain from performing the Beatles number again, and also to cease from kicking away his piano stool – à la Jerry Lee Lewis – during Bennie and the Jets. A few years earlier, the British establishment feared that punk rock might bring an end to society as they knew it. Now, the top Soviet brass seemed fearful that Elton John rearranging the furniture could whip the oppressed hordes into a frenzy.

John chose to ignore the demands. He continued to close each performance with Back in the USSR for the rest of the tour, although the authorities did succeed in bringing their heavy hand to bear: At the second performance, John was surprised to see less enthusiasm from the audience. He later discovered officials were forcing fans to sit down as soon as they attempted to stand up or dance.

While in Leningrad, John – accompanied by his Soviet minders – took in the sights, including a visit to the Peterhof Palace and a boat ride around the city’s waterways. A trip to the Winter Palace was apparently abandoned due to a hangover.

Once the four shows were over, the tour party prepared to return to Moscow by train. Fans gathered at the station to send him off, throwing flowers and gifts towards him. Well aware of the hardships endured by the Russian people and the inflated prices they would have had to pay for the items, the farewell moved the singer to tears.

Once back in the capital, John and his entourage noticed a distinct change in atmosphere, with a greater sense of being monitored by the authorities on their tour of the Moscow sights. These included a trip to watch a football match between Dynamo Moscow and a Red Army side, a reception at the British embassy, and a performance of Swan Lake by the Bolshoi Ballet. On a visit to Red Square, where John struck a Cossack dance pose for photographers, John told the press of his aversion to discrimination in sport, whether based on colour, class or sexual preference. The Russian interpreter who translated these comments omitted any reference to sexual preference.

John and others also sensed that the audiences at the concerts were more reserved than they had been in the relatively more liberal Leningrad, as if the already skewed ratio of party officials-to-fans had become even more exaggerated. That said, John continued to mingle with fans on his tours of the city and the concerts went well.

All four performances at the Rossiya State Central Concert Hall went off without incident, with the performers remaining on their best behaviour, at least until the closing moments of the last gig.

With the night almost over and the plane ride home imminent, John and Cooper blistered through The Who’s Pinball Wizard, after which the singer downed a glass of vodka which he then smashed on the stage.

The incident might have raised eyebrows, but the Soviets couldn’t have been happier with the tour. Officials might have been a little perturbed by the passions he had undoubtedly unleashed, but John’s visit had certainly proved a welcome distraction in a country rapidly running out of everything, and had made the Soviet Union appear a little less austere to outsiders.

The artist himself was similarly delighted with events – his only complaints concerned the delay at customs, the train journey to Leningrad, the ‘interesting’ food and the lack of air conditioning. (The tour took place in one of the hottest Russian summers in memory – not that that stopped John wearing a Watford FC scarf on some excursions.) John returned to the UK elated at having pulled off such as massive publicity coup. Like the Soviets, he was pleased he had satisfied both intended audiences – his Russian fans and those back in the west.

For David DeCouto, author of Captain Fantastic: The Definitive Biography of Elton John in the ’70s, the visit was “the single most important step forward in east-west relationships since Khrushchev visited Hollywood back in ’59”. Even on a cultural level, this may be a little hyperbolic. Other Western musical acts had ventured east before John, including Cliff Richard and Boney M. And other, even more consequential, musical performances were to follow, such as Bruce Springsteen’s huge 1988 concert in East Berlin.

Indeed, even as John’s Russia tour was doing its bit for east-west relations, a new Cold War chill was descending, with tensions mounting in Afghanistan. Soviet forces would invade the country in December 1979 and the following year’s Moscow Olympics – for which John’s tour had been a form of dress rehearsal – was duly overshadowed by the conflict and subsequent boycott.

That said, John’s tour had certainly added momentum to the forces that would ultimately dismantle the Soviet Bloc. The communist authorities had made a significant concession to the power that western culture exerted in the east, and had proved themselves incapable of fully controlling the dynamics this unleashed. The pace of change in the Soviet system was famously slow but small, imperceptible shifts were starting to work away at the foundations of the communist regime. They would complete their task little over a decade after Elton’s visit.

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37