As the Third Man turns 70, JAMES OLIVER considers a movie often called the greatest British film ever made.

Allied bombers did a thorough job on Vienna during the war. What had once been one of Europe’s most gilded cities – setting for however-many lighthearted operettas – was left, like most of the continent, just so much ash and rubble.

Rebuilding had scarcely begun in 1947, when Graham Greene pitched up to research his next project; there was running water and the lights were working (for the most part) but the one-time seat of the Hapsburg empire was still largely a giant bomb site. But, given the story he had brewing, that suited Greene just fine.

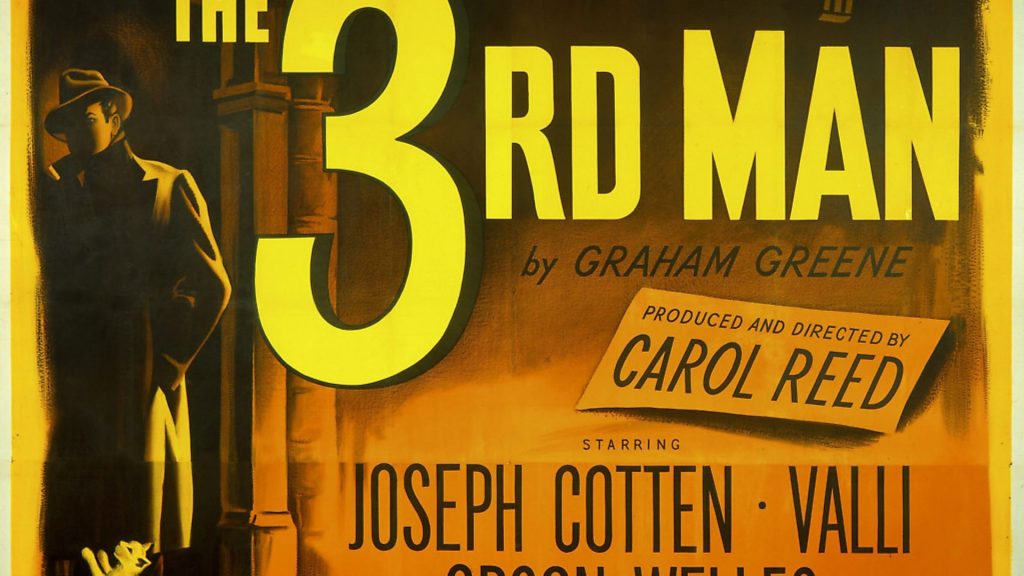

The results of that trip was a script that became The Third Man. As directed by Carol Reed, it was an instant success, an easy classic and, according to many polls, the best British film ever made. It celebrates its 70th birthday this month, and does so with all appropriate trimmings, including a return to cinemas.

But calling it a ‘classic’ can feel like a cop-out, suggesting worthiness and dusty venerability rather than a still-vital thriller that retains its power even after its plot twists have been unveiled (be warned: spoilers ahead). It’s worth going back before it became familiar and respectable to see what an unusual film it was, something so very different to the conventional entertainments of the day.

Greene went to Vienna at the behest of producer Alexander Korda. He’d worked with Greene and Reed on another film (The Fallen Idol) and all three were keen to work together again. What’s more, Greene had an idea. Leafing through his notebooks, he’d re-discovered a couple of sentences he’d jotted down a few years before. Looking at them again, he found them an irresistible starting point: “I had paid my last farewell to Harry a week ago, when his coffin was lowered into the frozen February ground, so it was with incredulity that I saw him pass by, without a sign of recognition, among the host of strangers in the Strand.”

Korda set him to work at once, although there were a few stipulations, like the location. Korda’s financial obligations were obliging him to film abroad. Money was less liquid in the 1940s, and not a few countries had installed strict credit controls to prevent foreign companies from remitting their profits abroad, rather than re-investing them when they were actually earned.

The Viennese setting of The Third Man, in hindsight so essential, came about because Korda wanted to make use of a pot of money he had waiting for him in Austria, where his films had proved especially popular. The same reason explains why it has American stars: the Labour government of the day had imposed credit controls of their own, and Hollywood producers were keen to make deals that would allow them to spend their British profits. Mogul David O. Selznick agreed to co-produce, provided they use a couple of his contracted players – Joseph Cotten and Alida Valli – to help sell the picture in the States.

The story Greene cooked up was far from typical Hollywood fare though. He’d soaked up the atmosphere of the new Vienna, characteristically attracted to the sleaze and moral decay, a swamp into which his hero would blunder. This hero – played by Cotten – was Holly Martins, a writer of dime store westerns bidden to Europe by old pal Harry Lime. Alas, he arrives just in time for Harry’s funeral. With his pulp novelist instincts twitching, Holly detects foul play and resolves to find the culprit.

This he does rather more quickly than he might have thought, finding that Harry – played by Cotten’s old mucker Orson Welles – is alive and well and up to no good: Lime is one of the worst black marketeers around, trading in things more dangerous than nylons and cigarettes, and utterly untroubled by conscience.

These were the prime years of what critics would later call Film Noir, pessimistic movies with flawed heroes and unhappy endings. But even by these standards, The Third Man is strong stuff, reflecting on the cataclysm of the war and the capacities for horror that conflict revealed.

The clear-cut justice that Holly peddles in his novels can’t help anyone here and the villain is far more seductive than anyone on the side of law and order, especially poor, ineffectual Holly.

It builds to a final scene that remains devastating no matter how many times you’ve seen it, and an indelible final shot. This, though, was not the work of Graham Greene; mindful of the conventions of the screen, he had penned a happy ending that allowed at least a modicum of closure. But that was before Carol Reed set to work.

Reed’s contribution to The Third Man remains hugely underrated. Jostling for attention with Greene on one side, and Welles (who was barely on set) on the other, it’s easy enough to assume that Reed did little but say ‘action’ and ‘cut’.

Make no mistake, though: More than anyone else, he shaped The Third Man. If Korda’s financial obligations obliged them to shoot in Vienna, it was Reed, and his cameraman Robert Krasker, who brought out the city’s texture.

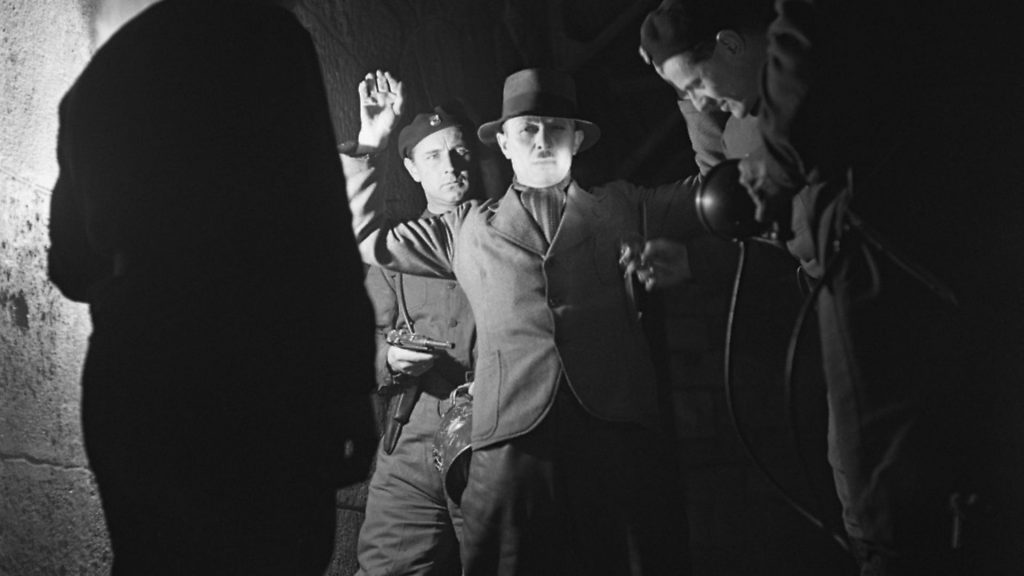

Reed’s Vienna is at once grimly realistic and nightmarishly expressionistic, where giant shadows project onto broken buildings. Audiences of the time would have been familiar enough with bomb damage but would never have seen it as vividly as this.

There was a vogue for ‘neo-realism’ at the time, stripping away glamour to show the world as it really was, but Reed goes further, beyond documentary to show at least something of the psychic damage of the war. That was why he dumped Greene’s original ending – it was phoney.

Reed also had to wrangle with the egos of American actors, a very different breed to the British variety he was used to. Cotten was good natured but Welles required a wee bit more work. Then in self-imposed exile in Europe, he was taking roles to raise money for his own movies (his version of Othello, in this case) and seldom bothered to hide his disdain for the work.

The Third Man was different, though. Recognising the quality of both script and director, he was only moderately awkward (refusing to enter the Viennese sewers for the final chase, obliging sets to be built in London) and gave one of his best screen performances as Lime, drawing on every piece of his own considerable charisma to invest his character with the charm of the devil. (So popular was he in the role, he would play a more heroic Lime in a long running radio serial, set before the events of The Third Man.)

Welles was not always above claiming credit for the work of others but in later years, he would always correct those who tried to attribute any part of The Third Man to his hand. Nope, he’d tell them, that was all Carol Reed, one of the biggest compliments he paid any of his colleagues. (The actor did make one very significant contribution. The most famous scene of the film is the meeting of Holly and Harry on the Wiener Riesenrad, the large Ferris wheel in the Prater amusement park, which somehow survived the various bombing raids. Welles supplied the coda, one of the most famous speeches in movie history: “You know what the fellow said – in Italy, for 30 years under the Borgias, they had warfare, terror, murder and bloodshed, but they produced Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci and the Renaissance. In Switzerland, they had brotherly love, they had five hundred years of democracy and peace – and what did that produce? The cuckoo clock.”)

There’s one more collaborator who needs to be mentioned. Keen to emphasise the sense of place, Reed wanted the music to reflect Vienna but wasn’t sure how to do that until he heard Anton Karras in a cafe. Karras was just a jobbing musician who played the Zither – a stringed instrument much favoured in Alpine regions – but Reed knew he had his man.

Karas came up with a tune that became a genuine sensation – the The Third Man Theme was one of the top selling discs of both the 1940s and the 1950s, becoming a staple of every musical group’s repertoire (yup, even The Beatles did ‘Harry Lime’). Karras took full advantage, proceeding to tour the world and twanging his strings for the great and the good, before retiring to open his own club in Vienna.

It’s tempting to suggest that it was Karas’ music that made The Third Man such a box-office success. After all, the film is otherwise light on the sort of escapism that has traditionally been the main attraction of a night at the pictures.

We should not, though, underestimate its original audience: it arrived during a brief moment when people were prepared to face the subjects it confronted: the immediate euphoria of victory had faded, the consumer boom of the 1950s still just a dream, and the onset of the Cold War was presaging a very uncertain future (Vienna, like Berlin, was initially divided into sectors by its Western and Soviet occupiers).

It remains potent, even for those of us who have never seen a ration book. The enduring themes and the brilliant craftsmanship with which it is wrought prevent it from becoming a museum piece. Whether it’s the best British film ever made is a personal choice, but it cannot be ignored.

The Third Man is re-released nationwide on September 29 in ‘4K’ ultra high definition. Some screenings will feature a filmed Q&A – involving Angela Allen, who as a 20-year-old was part of the original production crew, and director Hossein Amini, hosted by Matthew Sweet – and a performance by Viennese zither player Cornelia Mayer.

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37