Bonnie Greer on the impact of Marvin Gaye’s What’s Going On, one of the greatest albums of all time, 50 years after its release

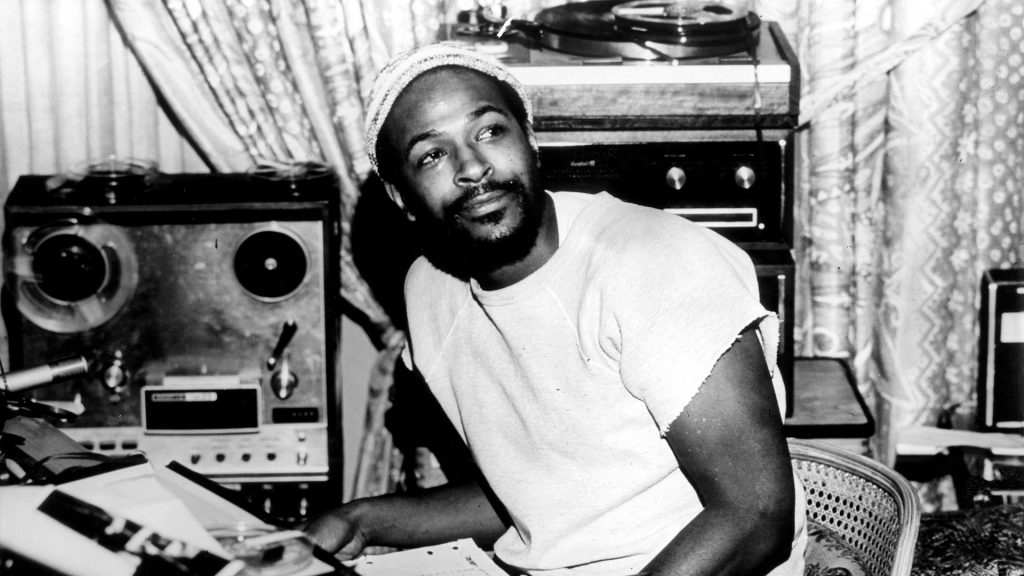

Growing up African American and a sheltered Catholic schoolgirl on the South Side of Chicago, Marvin Gaye was the “ooh baby, baby man”.

He was the troubadour of our clandestine basement parties, all soft lights and boys, allowed in by our strict parents, a concession to our raging hormones and to reality.

They were children themselves, children of The Great Migration, that exodus of African Americans from the rural South to the industrialised North right after World War I. They carried the Southern accent of their parents and therefore so did we, and our vowel sounds were their vowel sounds and so were Marvin Gaye’s.

Our nice cosy homes were bought from white people who had fled to the suburbs to escape us, but we kids only knew the reality of lawns, flower beds, quiet and gentility as our right. We knew nothing of pain.

My cousins lived on the other side of Chicago, in a 21 story concrete high-rise known as a project, where the playground was concrete, too, and you took your life in your hands in the lift and the stairwell. Rape was what a female expected and a gun in your face was what a male expected and so we saw that side of life on an occasional weekend.

What connected us was the soul of Motown and when Berry Gordy decided to pack up and move to Hollywood, well for us genteel kids: they had been there already.

Our TV screens were filled with the bouffant hair of The Supremes and Marvin himself as Mr Slick, in a suit and tie being a ‘mella kinda fella’.

We saw the Vietnam War, too, on TV, the backdrop to our suppers. The most popular guy in my high school, Richard Penniman, a smiley, gregarious guy who fancied me – but it took me a while to understand that – was drafted soon after graduation. He went to Vietnam, stepped on a mine and was no more.

He was the first contemporary of mine to die, and I would sit up at nights trying to imagine him dead and if he was anywhere.

I went, every other Saturday afternoon to have my hair straightened, a ritual which in those days involved lye, and you knew, as your hair looked like white people’s, that this was the price of that and it was good because it was the style. So what if your hair burned and you had scabs on your scalp, it was worth it for the fact that your hair moved in the breeze and you could ruffle it.

It was cars; and radios, and profile in my swank high school, a rival to Chaka Khans’s more ghetto school, a few neighbourhoods away, where she would, after my high-school time, become a teen legend with that voice and style.

Older guys were going to the ‘Nam and coming back to what they called “the world”, where we were, and where they had been; talking of “tripping bushes” near the battlefield where you could get high before you went into oblivion.

Those friends had become something else: broody; quick to loud laughter for nothing; angry; so angry, and tears just on the edge of the eyes. At 16 you know nothing and you know everything, and too much and not enough, and the War had brought it all home.

I had begun to realise that every boy I knew, even in our neighbourhood with its garden parties and quiet on the stoops, had had a gun to his face-legal or otherwise. Dr King got assassinated one warm spring evening and the world came to an end. We had grown tired of his admonition to turn the other cheek but he was still our father and he had been killed by hatred.

The community exploded and the streets burned and many lived in the rubble and debris; some shooting up on the drugs peddled there, and existing in the destroyed city parks, once havens and now charred. There was nothing and there was everything like the way it is when you are too young to know that an epoch has ended.

We were black and we were proud and we were kids who had to find our way. I went to university for one year full time, the rest of my degree had to be earned part-time because I had to pay my own way. I had to work. That one year as a full-time student was the year that I met Fred Hampton, only a few months older than me. I was too young to know that I was in the presence of a great man because great men are old. So I thought.

He had a breakfast programme for children in the neighbourhood my cousins lived in, that area of broken glass and broken playgrounds and there, we served breakfast with him. I can still see the long tables, like the tables in a monastery refectory and the children sitting quietly as we served the plates of food that their families could not afford. It was good, Southern fare: grits; biscuits; bacon; gravy and orange juice. Milk, too, if we could get it.

Fred and the Panthers stood security when we took over our campus one day to teach Black History, lecturing our bemused and frightened professors. We were pompous and earnest as the young can be, and Fred stood there with his dimpled smile and watched and listened to the whole thing.

I cut my hair soon after and wore no more chemical straighteners in it to this very day. We were surrounded by change and death and I needed to understand. Then, in May of 1971, the ‘stubborn kinda fella’ released What’s Going On?. There were a lot of protest songs by then, but no one was prepared for this. A black man did not sing protest as such. That was reserved for white people because our very being was a protest, we didn’t need to sing about it. So we thought.

But Marvin Gaye did. All of the voices on the record were his and each song was underpinned by rage and by love. Love for everybody and everything. That rage and that love caught us and the whole world by surprise. It changed us. Still changes me.

Some music you listen to, and some music you live.

The music you live is always there and sometimes it comes in waves and surfs you back to the time and the place of it.

You have to recalibrate yourself, then check yourself against your own youthful values and dreams.

The stuff you’ve failed and the stuff you’ve lived.

What’s Going On is present tense.

BONNIE’S TOP 20 TRACKS FROM 1971

Funky Nassau – The Beginning Of the End

Yours Is No Disgrace – Yes

Never Can Say Goodbye – The Jackson 5

Imagine – John Lennon

Just My Imagination – The Temptations

Riders on the Storm – The Doors

Let’s Stay Together – Al Green

Won’t Get Fooled Again – The Who

Theme From Shaft – Isaac Hayes

Me and Bobby McGee – Janis Joplin

Clean Up Woman – Betty Wright

It’s Too Late – Carole King

Changes – David Bowie

Rock Steady – Aretha Franklin

Aqualung – Jethro Tull

Have You Seen Her? – The Chi-Lites

Tiny Dancer – Elton John

Respect Yourself – The Staple Singers

A Horse With No Name – AmericaBut my favourite 1971 track is…

Stairway To Heaven by Led Zeppelin. I can still see myself when I first heard it at some bohemian university party on the North Side Of Chicago, doing too much of what we weren’t supposed to be doing. And then this record came on. I literally stood and stared at the vinyl. It was awesome.

My hubby, David and I have different tastes. But I still love him. His 1971 was: I Am I Said by Neil Diamond.

What do you think? Have your say on this and more by emailing letters@theneweuropean.co.uk

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37