On the night of Sunday, May 8, 1988, BBC2 premiered a newly-extended version of the British cult classic The Wicker Man, a picture once described as “the Citizen Kane of horror movies”. Before the movie played, however, viewers were invited into a mocked-up American motel room, with a garish pink and blue neon sign blaring outside the window. A young chap with an electric shock haircut and a leather jacket sidled in to talk a little about Robin Hardy’s picture and the season of outsider films for which it marked the beginning.

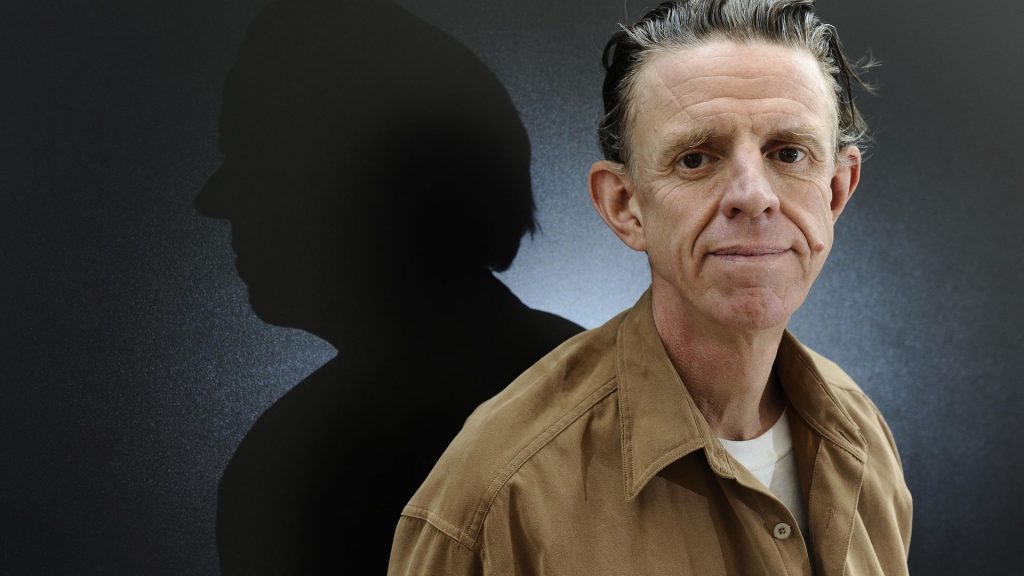

The man in question was Alex Cox, the Merseyside filmmaker then riding high on a quartet of films – Repo Man, Sid and Nancy, Straight To Hell, Walker – any or all of which could convincingly sport the cult movie mantle. The sign outside the window read: Moviedrome.

If you’re a film fan old enough to remember the 1980s, you’re almost certainly familiar with the cult movie strand. Others still might have chanced upon one of Cox’s introductions on YouTube, where a healthy number are now enjoying a fresh lease of life.

On that opening night, he explored the nature of cult films – “they share common themes: Love, murder and greed.” Future editions would see Cox introduce Terry Gilliam’s Jabberwocky with a recital of the Lewis Carroll poem that inspired it. When he put the case for John Landis’ An American Werewolf In London, his remarks were constantly being interrupted by a local lycanthrope.

Over 30 years on, Alex Cox might have cast aside the jacket and the haircut, but he still has a lot to say about the programme that made him as much a Sunday night staple as Songs Of Praise and One Man And His Dog. Not that he wants to hog the credit for Moviedrome. On the contrary…

“I think the virtue of Moviedrome was the good taste of [producer] Nick Friend-Jones,” Alex explains in a free moment between teaching writing and directing classes at the University of Colorado Boulder. “Nick delved time and again into the lower depths of BBC film acquisitions and surfaced bearing amazing gifts.”

Amazing gifts indeed. For if you’ve grown used to seeing the same movies air time and again on the terrestrial channels, imagine what it was like to turn on the telly late night Sunday to find the Peter Fonda acid western The Hired Hand or John Milius’ surf epic Big Wednesday or as prime a slice of Ozploitation as Russell Mulcahy’s big pig picture Razorback!

“There was no obligatory theme,” Alex continues, “so we could show almost anything – and at the outset it was possible to screen foreign language films.” Early non-English language Moviedrome offerings included Jean-Jacques Beineix’s Diva, The Long Hair Of Death – a barking Italian horror picture featuring the striking British actress Barbara Steele – Akira Kurosawa’s Yojimbo and Jean-Luc Godard’s Alphaville.

And the best thing of all about hosting? “I wasn’t obliged to be totally upbeat or read a press release!” enthuses Alex. “I could criticise the film, emphasise its bad points, isolate the good. This wasn’t your standard ‘film hosting’.”

Curated movie seasons certainly weren’t a new thing as far as BBC2 was concerned. Film Club had been on air throughout the 1980s with the likes of Derek Malcolm and Alexander Walker giving context to pictures the likes of Jim Jarmusch’s Down By Law, George Lucas’ THX 1138 and Rudolph Mate’s DOA.

Since all three of these films also appeared in early seasons of Moviedrome, it’s interesting to contrast the style of introduction. For while the Film Club précises are sober affairs, with more than a slight whiff of the Open University about them, the ‘Drome intros are almost conversational. They also occasionally took place in exotic locations such as Central Park or Alcatraz Island – not that exotic, true, but far removed from the bloke in a brown suit with a beige tie talking directly to camera in a room decorated by someone with a thing for tope. Put another way, while Film Club upheld the idea that cinema is for some people more than others, Alex Cox and Nick Freand-Jones seemed determined to point up that movies – even bizarre, niche movies – are for everyone.

Don’t forget that, when Moviedrome began to air, Empire magazine was yet to hit the shelves and the world wide web was just a really neat idea Tim Berners-Lee had had one morning over coffee. If you wanted film news and reviews, the place to turn was Sight & Sound; then as now a superb publication, albeit one that isn’t out to court the casual film fan.

Moviedrome whiffled through this world of serious film study like the freshest of breezes. Those who feared that understanding cinema required a degree and/or a French-English dictionary, here was a programme that provided a way of seeing and appreciating movies that was the furthest thing from dry and poncy. No, Moviedrome was a programme out to ask the really difficult questions such as “Where do all the long coats that you see in westerns come from?”, “Does not one lone dissenting voice feel that The Shining‘s a boring film?” and “How come nobody’s called Ossie anymore?”

In that first episode, our host even made a brave attempt to explain what a cult picture actually is: “A cult film is one that has a passionate following but does not appeal to everyone. James Bond movies are not cult movies but chainsaw movies are… One thing cult movies have in common is that they’re all genre films – for example, gangster films or westerns. They also have a tendency to slosh over from one genre to another, so a science fiction film might also be a detective movie and vice versa,”

And as for your typical Moviedrome movie, “It was probably financed by a major studio that fired the director halfway through and then pulled out entirely, leaving the cast to pool their savings and finish the film in another country, under the directorship of a generous used-car salesman.”

Such irreverence also characterised Moviedrome‘s titles. From a charming Third Man pastiche to the sight of our host sharing screen-time with Fred & Ginger and The Thing From Another World, Nick Freand-Jones clearly had a ball putting the sequences together. And as someone with no end of affection for the original King Kong, how much fun must Alex have had donning a gorilla costume and scaling a replica of the Empire State Building that positively reeked of Valerie Singleton and sticky-backed plastic.

Over the course of their time together, Nick and Alex showed all sorts of movies at the ‘Drome. And thanks to the way in which the series was promoted, the screenings often felt like mustn’t-miss occasions. Take the trailer for the Moviedrome presentation of Stanley Kubrick’s – admittedly unmissable – Lolita; it left one feeling like you wouldn’t be able to proceed with life until you’d seen it.

As the years went on, however, the limits imposed upon Moviedrome became increasingly apparent. Alex Cox: “Because films like Carnival Of Souls and The Honeymoon Killers don’t necessarily attract the biggest audience, and as Nick was under an obligation to attract some viewers now and then, at times we departed from our brief to show commercial as hell super-blockbusters such as The Terminator.”

Now, since it was ‘inspired’ by episodes of anthology TV series The Outer Limits, James Cameron’s cyborg epic isn’t entirely lacking in cult appeal. The same, however, can’t be said for Leonard Schrader’s Naked Tango, a horribly glossy affair that looked as out of place on Moviedrome as Oswald Moseley on a kibbutz.

As Alex explained to this writer in an earlier interview, it was also becoming increasingly hard to get foreign-language films on air.

“Nick and I really wanted to show [Italian political thriller] The Mattei Affair. We were so keen, I actually recorded an introduction that ran to over 10 minutes. I assume it’s now gathering dust on a shelf somewhere, if it still exists at all.”

So it was that on Sunday, September 12, 1994, the shutters came down on Moviedrome for the last time. Alex Cox – who’d actually made two features during his time with the programme – went back to writing and directing. And Nick Freand-Jones? He continued to create highly informative, effortlessly entertaining film programmes for the BBC.

Programmes such as, er, Moviedrome. For just three short years after it left the airwaves, the ‘Drome reopened for business, only now with Edinburgh Film Festival programmer Mark Cousins manning the ticket booth. Cousins’ style was a little different to Cox’s and it took some getting used to. However, anyone who’s seen Mark’s epic documentary series The Story Of Film would agree that the Northern Irishman’s passion for cinema is both profound and infectious.

And when that run ended in 2000, the baton was picked up by… well, all sorts of people, really. On YouTube, Simon Kennedy dedicated a channel to the programme and created his own intros. In interviews, filmmakers like Ben Wheatley and Ali Catterall were quick to mention the series when asked about their influences. And echoes of Moviedrome are also to be found in Offbeat, Julian Upton’s survey of obscure British movies, and on Talking Pictures, a fabulous channel that at its very best feels rather like Moviedrome, only minus Mr Cox.

As for me, Moviedrome turned a person for whom film meant Indiana Jones and John Hughes into someone with such a passion for cinema, I could think of nothing I’d rather do than write about movies for a living. It’s lovely to be able to trace the beginning of a career to a particular moment – or in this case, programme. It’s nicer still that the person who provided that inspiration should turn out to be such a decent, modest chap.

When I mentioned earlier that Alex Cox’s early pictures were Moviedrome-friendly, you might have wondered whether any were shown on the programme. The answer is ‘yes’ – towards the end of season five, the ‘Drome screened Walker, Alex’s 1987 movie about the American pirate who made himself president of Nicaragua. No doubt some other filmmakers would’ve used this platform to rail against the idiot critics who’d dared to criticise their picture’s stance or sentiments. Alex Cox simply offered up a none-too-flattering review from the Monthly Film Bulletin in the interest of impartiality.

Outspoken except when offered the chance to talk himself up, Alex Cox really wasn’t your average TV presenter. And because of that, and thanks to him and Nick Freand-Jones, there was absolutely nothing average about Moviedrome.

Ten ‘Drome Delights: The pick of Alex Cox’s time at the Moviedrome tiller

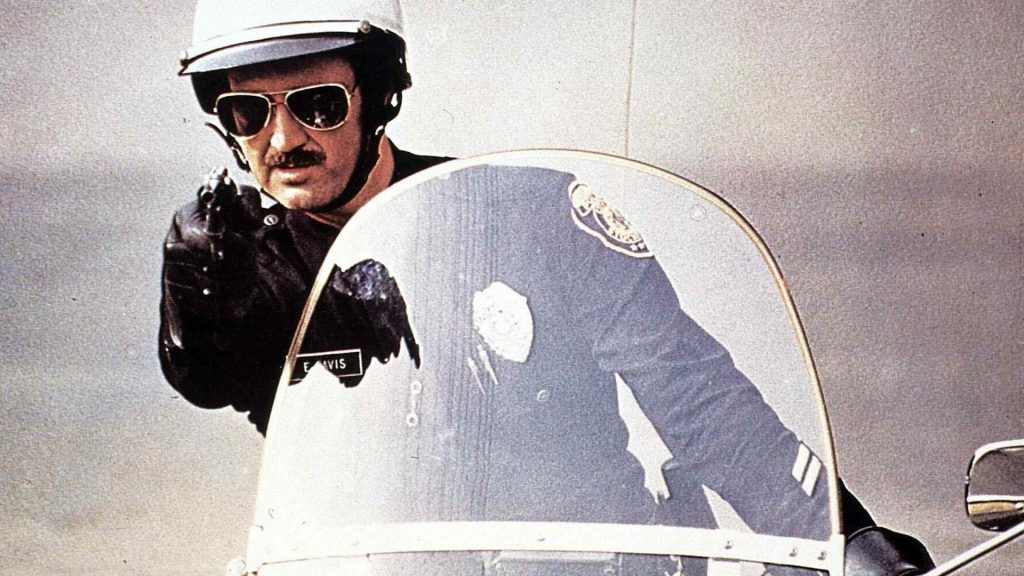

i) Electra Glide In Blue – A motorcycle movie that was the first and last film directed by music producer Jim Guercio and whose leading man is former child star and future alleged murderer Robert Blake; why, you can almost smell the cult from here.

ii) The Parallax View – The only picture to be shown twice during Alex’s stint at the ‘Drome, the second outing of Alan J Pakula’s political assassination masterpiece coincided with the 30th anniversary of the murder of John F Kennedy.

iii) Assault On Precinct 13 – John Carpenter’s low-budget inner-city remake of the Howard Hawks western Rio Bravo is the very stuff Moviedrome was made of. The Prince Of Darkness’s breakthrough picture Halloween also received an outing.

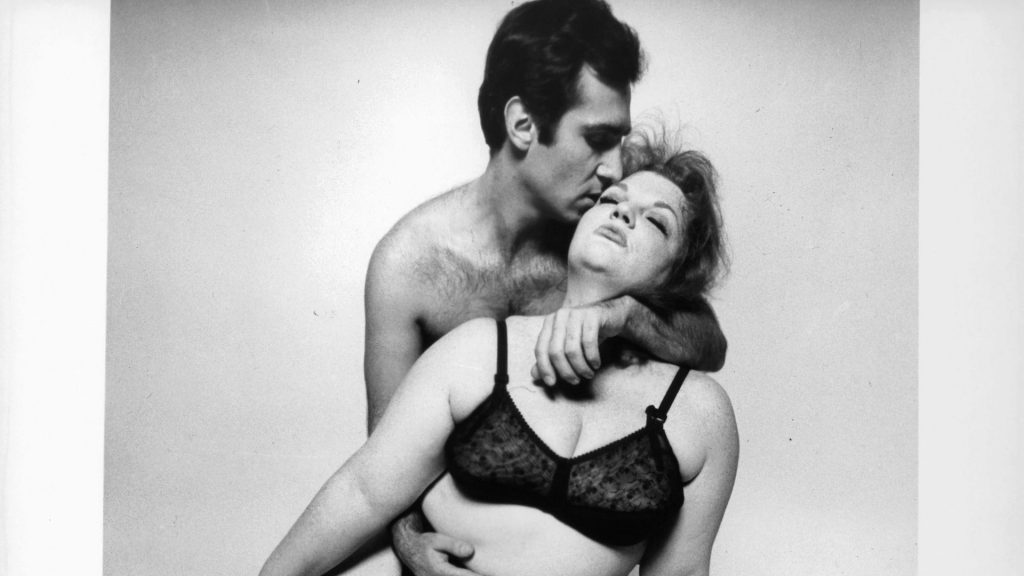

iv) The Honeymoon Killers – A story of mismatched murderous lovers, this bargain-basement feature began life as a Martin Scorsese picture; it was completed by Leonard Kastle who so enjoyed the experience, he never directed again.

v) The Great Silence – Arguably the best of the spaghetti westerns to appear on the strand, Sergio Corbucci’s picture stood out from that particular crowd since i) it hadn’t aired before on UK TV, and ii) it has the most upsetting ending of any film, western or otherwise.

vi) Carnal Knowledge – Perhaps the best example of the strange mainstream pictures that Moviedrome screened; Mike Nichols’ dark account of sex and the modern man features a Jack Nicholson performance that ranks among his finest.

vii) Bring Me The Head Of Alfredo Garcia – If anyone deserves the title of Moviedrome MVP, it’s character actor extraordinaire Warren Oates. As for the pick of his performances, it’s hard to look beyond his clapped-out bandito in Sam Peckinpah’s most personal picture.

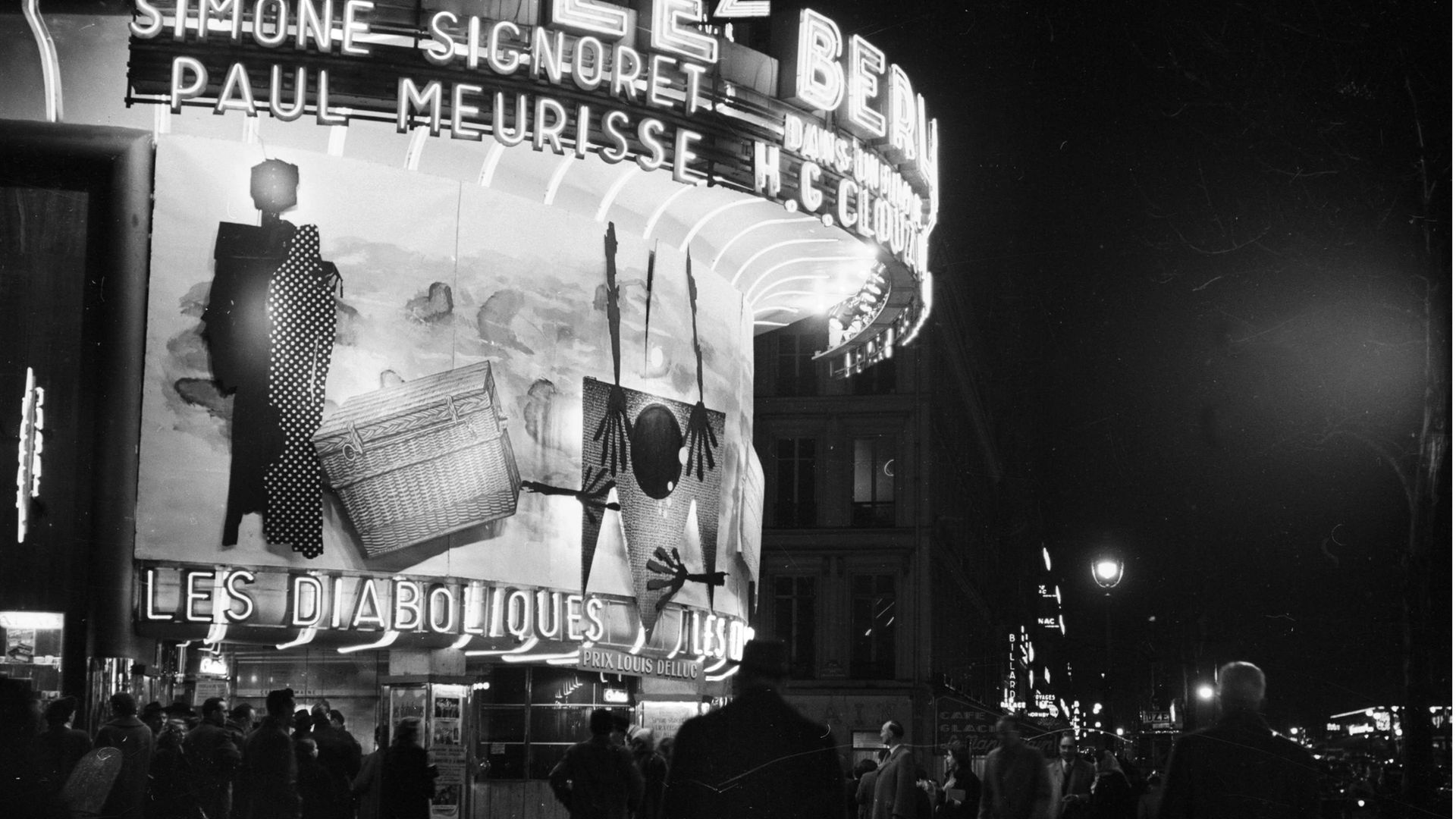

viii) Les Diaboliques – Besides showing films by Robert Bresson, Bernardo Bertolucci and Jean-Luc Godard, the ‘Drome also screened this European movie masterpiece; a Henri-Georges Clouzot thriller so suspenseful, it inspired Alfred Hitchcock to up his game.

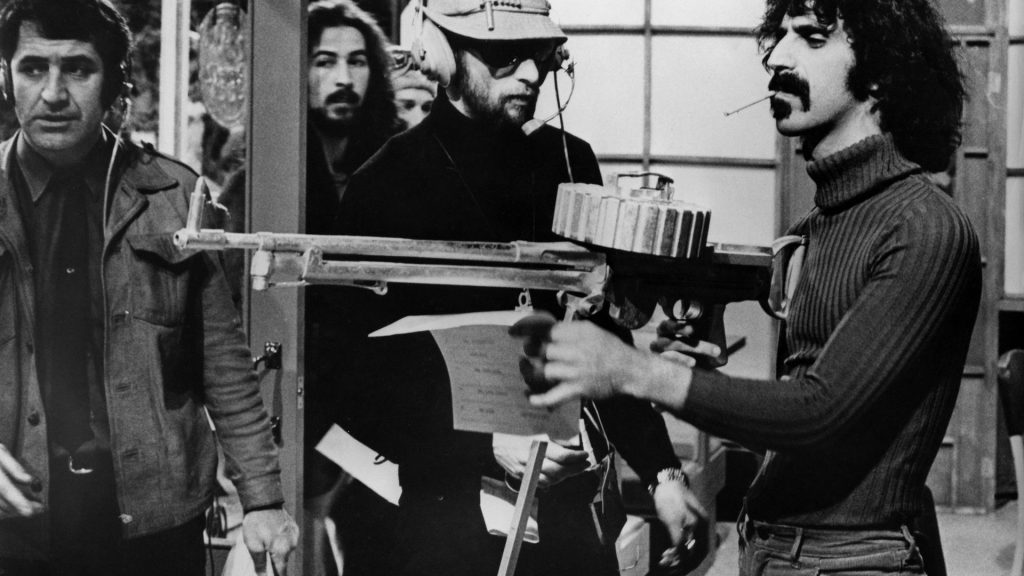

xi) 200 Motels – Described in Alex’s intro as a “200% cult movie par excellence”, Frank Zappa’s account of a hard-working band on the road features cameos from Ringo Starr as a dwarf and Keith Moon as a nun. In other words, it more than lives up to the description.

x) Kiss Me Deadly – The Cox era ended with this, a film whose director, Robert Aldrich, had more of his work shown on Moviedrome than any other filmmaker. That his atomic noir shares certain thematic concerns with Alex’s Repo Man was surely mere coincidence.

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37