On the eve of an American poet’s 80th birthday, the places and people over here broadened his horizons

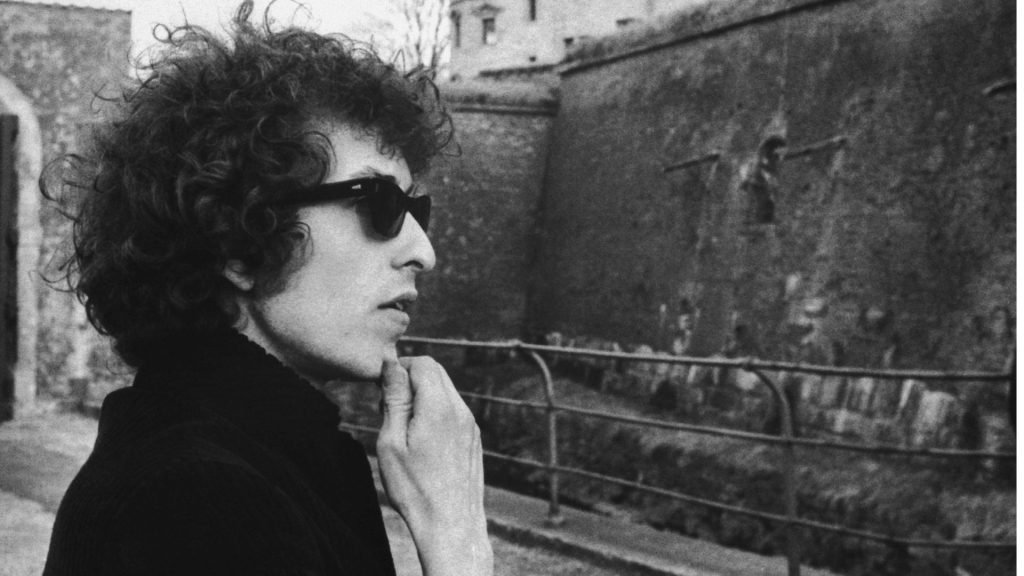

When he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature 2016 ‘for having created new poetic expressions within the great American song tradition’, Bob Dylan – who will celebrate his 80th birthday on 24th May – was clear that much of what had fed into this ‘American’ tradition was thoroughly European.

Four of the six fellow Nobel literature laureates he mentioned in his acceptance speech – Rudyard Kipling, George Bernard Shaw, Thomas Mann and Albert Camus – were Europeans. He also invoked Shakespeare and his Nobel Lecture spoke at length of Erich Maria Remarque’s All Quiet on the Western Front and Homer’s The Odyssey.

Even if it is a popular misconception that Robert Zimmerman adopted the name Bob Dylan via Dylan Thomas (he has dismissed the Welshman’s poetry as “for people who dig masculine romance”), this interpreter of the traumatic American experience of the 1960s and patron saint of Americana was in fact moved by the European imagination from his earliest days.

Literary, cultural and historical allusions from the old world pepper Dylan’s cryptic lyrics, a constant source of agonised scrutiny by Dylanologists, and when asked in 2008 to name the lyric or verse that his inspired him most, Dylan chose not a line from Little Richard, his teenage hero, or Woody Guthrie, his folk messiah, but Robert Burns’ A Red, Red Rose.

Last year’s Rough and Rowdy Ways was only the latest evidence of his Europhilia, as namechecks for Dylan’s fellow countrymen, both real and imagined, Walt Whitman, Edgar Allan Poe, JFK and Indiana Jones, gave way to Anne Frank, the Rolling Stones, William Blake, Frankenstein, Richard III, Hamlet, Freud, Marx and Julius Caesar.

But Dylan’s European influences did not just come in the petrified form of print on pages or the grooves in vinyl, and many a flesh and blood European and real-life, rather than merely imaginative, visits to the European landscape shaped his career when it was still an uncertain thing.

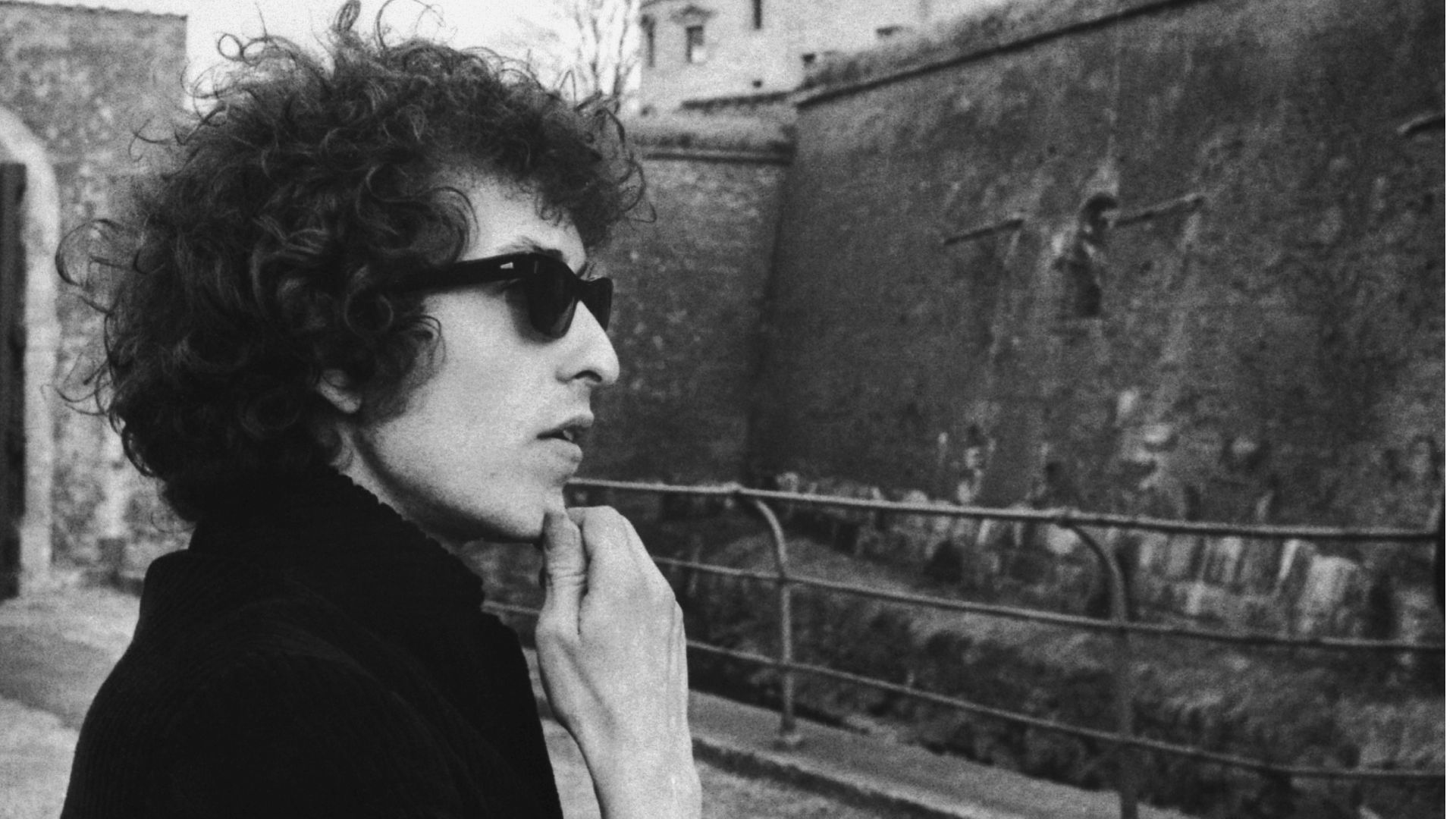

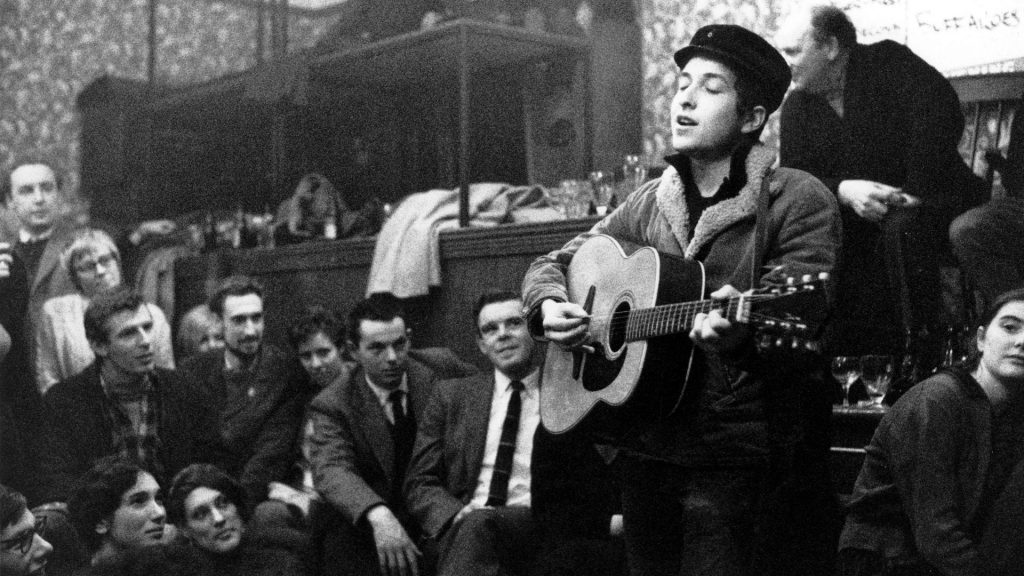

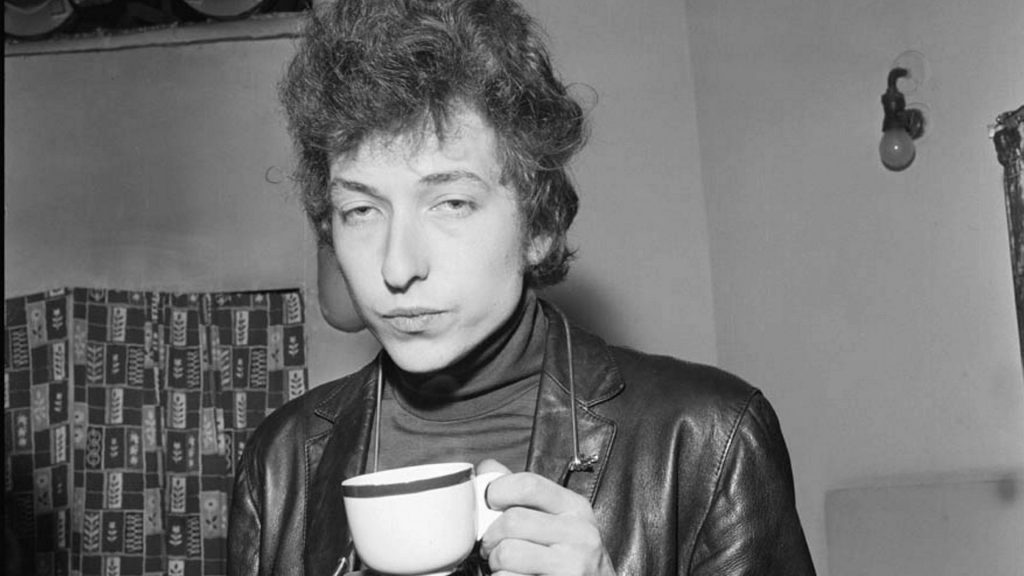

Dylan first set foot on European soil when he landed in London in the middle of the punishing winter of 1962. The Thames had frozen upriver and his reception from some on the London folk scene was just as frosty. When he met British folk singer Ewan MacColl after giving his first UK performance at the Singers’ Club at the Pindar of Wakefield pub on Gray’s Inn Road, the traditionalist was less than impressed and thoroughly standoffish.

But Dylan’s meeting with Martin Carthy at the Troubadour club was a rather warmer affair, and Carthy would have a profound influence on The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan (1963), Dylan’s second album but his first of original material. Carthy taught Dylan his arrangements of both the 19th-century ballad Lady Franklin’s Lament and Scarborough Fair just before the American departed for Rome in January to meet up with Suze Rotolo, his New York girlfriend who was studying art in Italy.

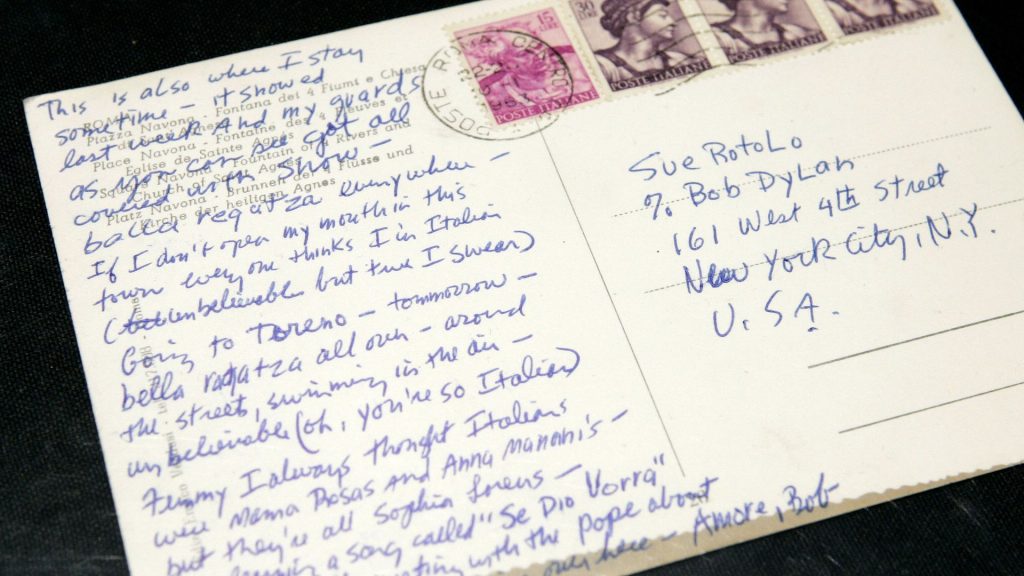

Dylan’s experience of Rome would be intense. He arrived to find his and Rotolo’s paths had crossed; she was back in New York, and he was homesick and lovesick in one of the most romantic cities in the world.

The result of this emotional maelstrom was a burst of songwriting. Carthy’s lament got reworked into Bob Dylan’s Dream, filled with imagery of Dylan’s native Midwest, while Scarborough Fair became the Rotolo-inspired Girl from the North Country. Scarborough Fair was also the blueprint for the fragile and wistful Boots of Spanish Leather, which later appeared on The Times They Are a-Changin’ (1964). According to Dylanologist Clinton Heylin, it was also inspired by the nursery rhyme Shoes of Spanish Leather, which “must be something he heard or read about on his trip to London”.

Under Dylan’s pen, old English ditties heard in grubby and thoroughly old-world London pubs improbably became songs bound up with the romantic difficulties of the hip young New York couple iconically pictured on the cover of the album on which those songs appeared. Carthy later said the UK trip was “crucial to [Dylan’s] development – it had a colossal effect on him”, and indeed while Dylan had told a reporter in London “I don’t like singing to anybody but Americans. My songs say things. I sing them for people who know what I’m saying”, the experience of Europe seemed to enlarge his imagination as he began to move away from the naked protest song and pushed towards universal themes.

The homespun, anti-capitalist British folk scene may have impacted Dylan, but he was hardly immune from what was going on at the other end of the commercial scale. The Beatles arrived in America in February 1964 and I Want To Hold Your Hand rocketed to No. 1. By early April they were occupying the entire Billboard Hot 100 Top 5. Dylan was reportedly entranced by their audacity and paid tribute to them in the ‘No, no, no’ device of his anti-love song It Ain’t Me Babe, echoing The Beatles’ ‘Yeah, yeah, yeah’ of She Loves You.

Dylan did not meet the Beatles until some months later, but in the meantime another European capital would fill his imagination. Paris – later memorably pronounced “Paree” to rhyme with “the sea” on his existential hymn Not Dark Yet (1997) – had already exerted a powerful influence over him before his late spring 1964 arrival. In February he had told a journalist “Rimbaud’s where it’s at”. The symbolist poet was synonymous with Paris’ literary demi-monde of the 1870s, and Dylan had already written Mr. Tambourine Man inspired by his poetic forms, its “magic swirling ship” a reference to his Le Bateau Ivre. He had already come a long way from the Dylan of 1962 who was interested only in messages an American audience could grasp.

While Dylan’s other pre-existing Parisian connection was to a living figure, it was to one who was – to him at least – almost as untouchable as Rimbaud. Françoise Hardy was the embodiment of French cool in the yé–yé pop era and Dylan had developed a full-blown infatuation with her from 3,500 miles’ distance after seeing her on TV. He wrote her a number of unsent letters and when the album Another Side of Bob Dylan appeared in August 1964, the poem filling the back cover included the lines ‘For Françoise Hardy/ At the Seine’s edge/ A giant shadow/ Of Notre Dame’. The two would not meet until two years later and even then, Hardy later admitted, the language barrier prevented meaningful connection.

But Paris also brought another example of European chic made flesh to Dylan’s attention. The model and actress originally from Berlin, Christa Päffgen – aka a pre-Warhol Nico – met Dylan at a pavement café and later claimed that he wrote I’ll Keep It With Mine both for and about her, and that she accompanied him when he went on from Paris to Greece where he finished most of the material for Another Side of Bob Dylan.

While Nico may have exaggerated the scale of her association with Dylan, his meeting with The Beatles in New York in August 1964 was undeniably momentous. Back in January, George Harrison had told the NME “I like his whole attitude”, and he would later make major contributions to Dylan’s career at crucial moments. But for now, when they finally came face to face in Dylan’s room at Park Avenue’s Delmonico Hotel, the exchange was mutual – Dylan introduced the band to weed and they gave him a new rock idiom. Al Aronowitz, the journalist who orchestrated the meeting, later put it: “The Beatles’ magic was in their sound. Bob’s magic was in his words. After they met, the Beatles’ words got grittier, and Bob invented folk-rock.”

This was perhaps a little too neat, but Bringing It All Back Home, released in March 1965, with its whole side of electrified music did indeed shake music to its foundations. But European ideas were influencing not just Dylan’s sound but his increasingly impressionistic lyrics.

By the time he met William Burroughs in a Greenwich Village café that spring, he had already written verse reminiscent of the cut-up technique Burroughs developed alongside British-born artist and cultural catalyst Brion Gysin in Paris in the early 1960s. It was not an instant meeting of minds, and Burroughs later admitted: “ had no idea who Dylan was”. Still, Desolation Row, the queasily surreal 11-minute closing track of August 1965’s fully electric Highway 61 Revisited, seemed to bear Burroughs’ influence and Burroughs’ close friend Allen Ginsberg featured in the promotional clip for Subterranean Homesick Blues, filmed behind London’s Savoy Theatre on May 8, 1965.

But as much as Europeans had been heaven-sent muses to Dylan, as he turned electric, they became demons dragging him down. After releasing the searingly iconoclastic Like A Rolling Stone in July 1965 – a song Heylin believes was begun in London that May and may have been partly inspired by Marianne Faithfull – and debuting it at Rhode Island’s Newport Folk Festival a few days later to boos, he was slaughtered in the September 1965 issue of Sing Out! folk magazine by none other than Ewan MacColl. He wrote: “Only a completely non-critical audience, nourished on the watery pap of pop music, could have fallen for such tenth-rate drivel.”

The heat had not gone out of the controversy eight months later when Dylan played his famous Manchester Free Trade Hall gig. The first half had been wholly acoustic, but when he took to the stage after the intermission toting an electric guitar and with his full band, slow handclaps began. Then, just before the finale, a lone voice from the second balcony shouted “Judas!”

Time stood still. But then the crowd began to applaud and Dylan sniped back “I don’t believe you… You’re a liar”, before instructing his band to “Playing it fuckin’ loud!” and going into an incendiary rendition of Like A Rolling Stone. Circulated on a bootleg record for years, it became a defining moment of Dylan’s career, crystalising his reputation as a figure more concerned with satisfying his own creative muse than his audience. While others have claimed to be the heckler, it seems like John Cordwell, a Cumbrian teacher training lecturer, was the likely culprit, a Brit unwittingly changing the way an American legend was seen forever.

Shortly after the Manchester face-off, Dylan’s golden era ended with the release of Blonde on Blonde (1966) and then a motorcycle crash a month later that marked the start of a long period of reclusion, some of which may or may not have been spent on the Balearic isle of Formentera. By the time of the release of June 1970’s bizarre Self Portrait LP, he was being written off by critics.

But already Dylan’s rebirth was afoot, courtesy of a recently post-Beatles George Harrison. Less than six years on from getting stoned together at the Delmonico, Harrison and Dylan were back in New York for a historic jam session on May Day 1970. The session catalysed Dylan’s next LP New Morning (1970), which was seen as a return to form. Harrison would also secure Dylan’s return to the stage a few months later. It took an impromptu side stage counselling session from Harrison to do it, as Dylan had a last-minute crisis of confidence, but as he romped through a greatest hits set at August’s historic Concert for Bangladesh at Madison Square Garden, Dylan seemed to be back.

The soul-searching When I Paint My Masterpiece, appearing on the Greatest Hits Vol. II of late 1971, perhaps demonstrated just how much of a role the experience of Europe had played in transforming Dylan – once hemmed in by the limited description ‘American protest singer’ – into someone who was speaking to everyone. It took place “On a cold, dark night by the Spanish Stairs”, bringing to mind not just Dylan’s first trip to Rome but also Keats, who died in a house by the Spanish Steps and would later be earnestly compared to Dylan by literary critic Christopher Ricks.

But since the song was partly inspired by the Roman scenes of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s Tender is the Night, this was Europe seen through an American filter, and perhaps for Dylan – of Ukrainian and Lithuanian descent, and his foundation of ‘American’ folk ballads often in fact an inheritance from the European settlers – the distinction between the old and new worlds had blurred.

To take a phrase from his autobiographical Chronicles, it was all the same “culture of feeling”, but it took encountering Europe in reality for that to show in the songs.

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37