Herbrand Sackville, the 9th Earl of de la Warr, was a surprising character. He could trace his ancestry back to the 16th century, he owned swathes of land in southern England and he was elected as a Labour MP in the 1920s.

He was also mayor of Bexhill-on-Sea, East Sussex, where he put his conviction that the arts can rejuvenate a community into reality by persuading the town council to hold an international competition for the design of a seaside pavilion. It would provide culture and entertainment for the masses – a ‘people‘s palace.’ At the opening in May 1935, he declared it would become “a crucible for creating a new model of cultural provision in an English seaside town which is going to lead to the growth, prosperity and the greater culture of our town”.

Designed by leading modernist architects of the day, Serge Chermayeff and Erich Mendelsohn, a refugee from Nazi Germany, The De La Warr Pavilion is one of the glories of the south coast, standing boldly above the shingly beach, its clean white lines the result of a revolutionary use of concrete, steel and glass.

The earl was ahead of his time; today art and culture are increasingly employed to cheer up dilapidated seaside towns and in that spirit, seven resorts have come together to form England’s Creative Coast in a project entitled Waterfronts. Seven artists have contributed new works in south coast venues stretching from Southend-on-Sea to Margate and along the coast to Eastbourne – all resorts which were fashionable from the Victorian era to the 1950s, only to suffer decline and stagnation when cheap air travel whisked holidaymakers to sunnier European climes.

Each resort is displaying very different works, four by overseas artists, which are intended to bring an artistic spark to these seaside locations where history has ebbed and flowed, where travellers have arrived and departed, or sometimes stayed. As project director Sarah Dance says: “It’s all about connections. We are connecting people to places, artists with the coast, creative organisations with landscape and with each other, and about connecting visitors to the history of the people and places on the coast.”

Inevitably, the project is also about regeneration – attracting a greater number of visitors, offering them more to enjoy, encouraging them to spend their money, because all of the towns struggle with high unemployment, homelessness and drugs. Thanet, which includes Margate, is in the top ten of drug-related deaths per 100,000. None of this has been helped by successive governments using coastal towns as a dumping ground for refugees and benefit users with, for example, The Burstin Grand Hotel on Folkestone seafront filled to capacity with them for most of the lockdowns.

So what would the radical Earl de la Warr make of a giant worm-like creation outside the Pavilion which appears to burrow its way from the seafront lawn into the building to the first floor balcony and on to the roof?

Inverterbrate, by Holly Hendry uses bricks from the nearby works, sandbags made out of boating canvas and metal to represent digging into the earth and regurgitating the materials in a process of renewal. It’s a puzzling piece, apparently a “metaphor for precarity and change.”

Inside, an accompanying room of sculptures by Hendry titled Indifferent Deep imagines the effects of the invertebrate’s actions with the Pavilion as a porous body.

The earl, whose taste probably tended to the more classical – he owned four paintings by the Italian Niccolò di Pietro Gerini (c. 1340 – 1414) – would no doubt be delighted at the publicity the worm engenders and all the more pleased that since its 80th year in 2015 the Pavilion has increased its footfall from 400,000 (and more than £16 million to the local economy) to 420,000 in 2018.

As a socialist for much of his political career, he would have been impressed by a small show in a side gallery inspired by a Chilean woman who fled the Pinochet regime which oppressed her country from 1973 to 1990. All in the Same Storm: Pandemic Patchwork Stories reflects the lives of immigrants, the loss of lives under Covid, togetherness and isolation, with embroidery and video testimony. It is both simple and moving.

It is another Chilean, Pilar Quinteros, who has dreamed up the double-headed Janus Fortress: Folkestone which looms mightily on the cliffs above the harbour with its faces looking inland and out to sea to Europe. Named after the Roman god of doors and gates as well as more profound concepts such as life and death, war and peace as well as, perhaps, a nod to what some might consider the negative forces of Brexit.

The sculpture will be a star turn at the Folkestone Triennial which opens on July 22 but it is made of chalk and plaster and is designed to disintegrate or be demolished – one art lover has already joined in the spirit of the venture by knocking a chunk out of it – so hopefully it will still be standing come the end of the Triennial in November.

The event is an integral part of the resort’s renewal, which is built around the legacy of another wealthy art lover, Saga insurance–to-cruises entrepreneur Roger Haan, who grew up in the town.

In 2002, he bought 90 buildings and rented them at cheap rates to be used as studios, offices and shops and which have become the heart of a Creative Quarter with its narrow streets of galleries and craft shops, restaurants and coffee bars.

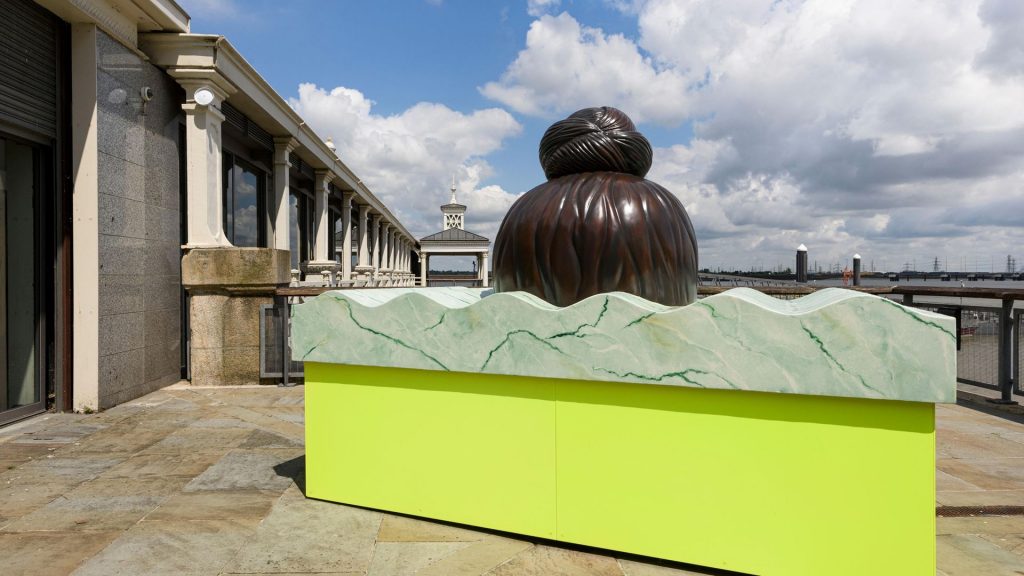

Almost as monumental as Janus is Jasleen Kaur’s sculpture of a Sikh’s head on the small pier in Gravesend, Kent. The first thing I did was kiss the ground celebrates the fact that Gravesend has become home to many Sikh immigrants. The dome-like figure of the sculpture is complemented by songs and reminiscences of the town’s Saheli women – Saheli means something like ‘Girlfriend Club’ in Hindi – which are played to people waiting in a shelter to catch the ferry across the Thames to Tilbury.

It is in Tilbury that one really does get a sense of connection with the comings and goings of history, for it was there that the Empire Windrush docked in June 1948, bringing the earliest immigrants from the West Indies.

Cruise ships call into the port today but the old customs hall is still standing as is the covered way along which the new arrivals would have made their first tentative steps in England. In Tilbury Bridge Walkway of Memories, set in the same gangway, the story of the Windrush generation is poignantly told in pictures, video and written testimony. This is not in the Waterfronts programme but well worth a jaunt on the ferry from Gravesend.

It feels more connected to place and history than the much-publicised sculpture April is the cruellest month by the American Michael Rakowitz, which stands on the front in Margate. It salutes a young British soldier who served with the Royal Artillery during the Iraq War. Rakowitz’s soldier turns his back on the shore and instead points inland towards London and parliament where the decision to go to war with Iraq was taken.

It is a striking image, no doubt about that, and although it is on the waterfront it doesn’t feel of the waterfront, and it is hard to understand how it relates it to the concept of “connecting visitors to the history of the people and places on the coast.”

In fact, there is a greater sense of sea, coast, people and places on the train journey which chugs along stopping at Hastings (where the Hastings Contemporary is also staging an installation), Rye, Winchelsea, Pevensey and finally Eastbourne. It’s a jaunt evocative of buckets and spades, ice creams and the Norman Conquest. John Betjeman should have written a poem about it.

The contribution by the Towner Gallery, Eastbourne is altogether more subtle than the Rakowitz soldier by being related to local legend and its own artistic legacy despite the fact – maybe because – it has been conceived by another overseas contributor, a Mexican based in Berlin.

Mariana Castillo-Deball took her inspiration from an archaeological find in Eastbourne made in the late 1990s of a number of funerary objects dating back to the Iron and Bronze ages including the body of a young woman who became known as The Frankish Woman, but more likely to be from sub-Saharan African 2,000 years ago and possibly a slave

In Walking through the town I followed a pattern on the pavement that became the magnified silhouette of a woman’s profile, she has taken sculptural copies of the finds such as brooches, placed them at intervals around the town and linked them with a blue line on the towns’ pavements. Follow the line, match it to the map which accompanies the walk, and there is the outline of a woman – the Frankish Woman.

The trail takes about two hours. It’s a pleasant stroll. It is also a connection to the past, a reminder of the tantalising piece of local history and perhaps, apropos the imperative of art as a force for renewal, a moment to reflect as you walk past the grand hotels on the front and the genteel back streets, that according to figures in May 2019, Eastbourne has had a small rise in homelessness and unemployment is among the highest in the south east.

Deball, whose work veers to complex installations, has been allowed to rummage through the Towner’s collection to curate an exhibition drawn from its collection called, A drawing, a story, and a poem go for a walk. It is a delightfully eclectic mix of Sussex landscapes and local artists, with Victorian scenes of the rural idyll, several abstracts, works in ink and sketches of fierce birds by Elizabeth Frink

As a bonus, there is an exhibition John Nash: The Landscape of Love and Solace which includes his war paintings, bucolic scenes but perhaps best of all, his wood engravings (Until September 26).

The most ambitious manifestation of Deball’s enterprise is a huge, 160-metre long hairpin, like one found with the body of the Frankish Woman, which she has had inscribed in chalk on Beachy Head Down, high above the town.

For the energetic, it’s a fierce walk out of town (or taxi ride – it’s steep) to find a vantage point to look down on the chalky hairpin with the Downs above it, the clifftop and the sea beyond. It is a spectacular sight, or should be. This is England. It’s summer. When I was there a sea fret came blustering in and the fabled hairpin became an indistinct blur.

Yet strangely, it added to the mystery of the Frankish Woman, her story almost lost in the time of mists.

Led by Turner Contemporary and Visit Kent, Waterfronts, England’s Creative Coast runs until November 12. www.englandscreativecoast.com

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37