Gender bias means that the history of art has been written by men, about men. But there are some signs that the tide is finally beginning to turn

It’s been 50 years since the pioneering feminist art historian Linda Nochlin posed the provocative question ‘Why have there been no great women artists?’ – a ground-breaking essay that cracked open the canon of Western culture to expose the gender biases that have meant that the history of art has largely been a history of art produced by men.

We might be tempted to presume that much must have changed in a half-century of ostensible gender equality, but in 2021, the National Gallery in London still only owns 21 works by female artists, and has only just produced its first-ever large scale retrospective of a woman artist (the Italian painter Artemisia Gentileschi). Annual reports on gender equality by the UK Freelands Foundation also reveal that the art market continues to disproportionately favour the work of men.

A glance at this crop of 2021’s international exhibitions in major institutions however suggests that museums are finally waking up to changing the dominant programming of ‘stale, male pale art history’ to make space for more artist women of colour and 20th century women artists. Why does all of this matter? To draw on the words of the artist-activist group The Guerilla Girls in their 1989 poster: “You’re only seeing half of the picture without the vision of women artists and artists of colour”.

A Black Hole is Everything a Star Longs To Be, which runs until September at the Kunstmuseum Basel will be the American artist Kara Walker’s first exhibition in Switzerland as she opens up her closely guarded archive of 600 drawings.

Walker’s mordant vision of the violence and horror of colonial exploitation and slavery has made her a central figure in 21st century art on a global scale. Her work examines the violent interrelation between blackness and whiteness – seen to devastating effect in her panoramic murals of cut-paper silhouettes from the 1990s that played out an unflinching antebellum horror story of rape and abuse of enslaved Africans.

Since then, Walker has received much attention for her experiments in public sculpture with works that probe different histories of race and empire than the ones that monuments tend to triumphantly memorialise.

In 2019 the artist created the Fons Americanus fountain for Tate Modern, a watery allegory of the history of the transatlantic slave crossings produced in response to the imperialist pomp of the Victoria Memorial outside Buckingham Palace. While in 2014 The Marvelous Sugar Baby, a 75-foot long sugar-coated sphinx with the head of the archetypal ‘black mammy’ (the enslaved domestic worker of pre-Civil war era America) took up temporary residence in the Domino Factory in Williamsburg that year providing an inescapable confrontation with the suppressed histories of exploitation and violence that underpin western history and culture.

At 51, Walker is very much the exception to the general rule that women artists tend to find public recognition either posthumously or in the twilight of their careers.

This summer Tate Britain stages the most comprehensive full-scale retrospective to date of Portuguese-born artist Paula Rego, who studied at the Slade School of Art in London after her family fled the repressive dictatorship of Antonio de Oliveira Salazar in the 1950s.

A touchstone for subsequent generations of women painters, Rego is widely known in British and international collections of art for her oneiric figurative images inspired by folk stories and fairy tales, but her work has also been deeply engaged with contemporary politics, much of which will be on show at the Tate.

In the Abortion Series of pastel drawings produced between 1998-1999, the artist confronted a theme that is all but invisible in western art, despite being a common experience among women. Schoolgirls squat over buckets of blood, women writhe on couches or sit and wait with vacant gazes for their unwanted pregnancies to be expelled by illegal and unsafe ‘backstreet’ abortion.

Rego produced the portraits in response to the failed 1998 referendum to legalise the termination of pregnancies in Portugal, later exhibiting them in Lisbon and influencing a national conversation that culminated in a change to the law in 2007.

Rego’s dignifying portraits subvert the traditional idealised depictions of femininity beloved of European art, and this theme continues in her ‘Dog Women’ series from the 1990s which depict women (alter-egos of the artist herself) in unexpectedly canine poses. Rego described the symbolism of the Dog Women as something empowering; “to be bestial is good… women are trained to do certain things, but they are also part animal.”

In contrast, Dulwich Picture Gallery puts aesthetic beauty rather than bestial power centre stage in Helen Frankenthaler: Radical Beauty, opening this autumn. This promises to be a long-overdue eulogy to one of the so-called ‘Ab Ex women’ group of mid 20th century American artists – women who until recently have been disregarded as mere satellites around the key male figures of the movement such as Willem de Kooning and Jackson Pollock (an encounter with the latter Frankenthaler described as a “beautiful trauma”.)

Frankenthaler, an elite Manhattanite, was credited with bringing the technique of colour-field painting into the brooding monochrome constellations of the Abstract Expressionism movement in the US, but this show focuses on her series of woodcut prints which she began in 1973, and which culminated in her magisterial Madame Butterfly from 2000, a symphony of colour inspired by Puccini’s 1904 opera, and which at 2 metres in length (made from 46 woodblocks) will occupy an entire room.

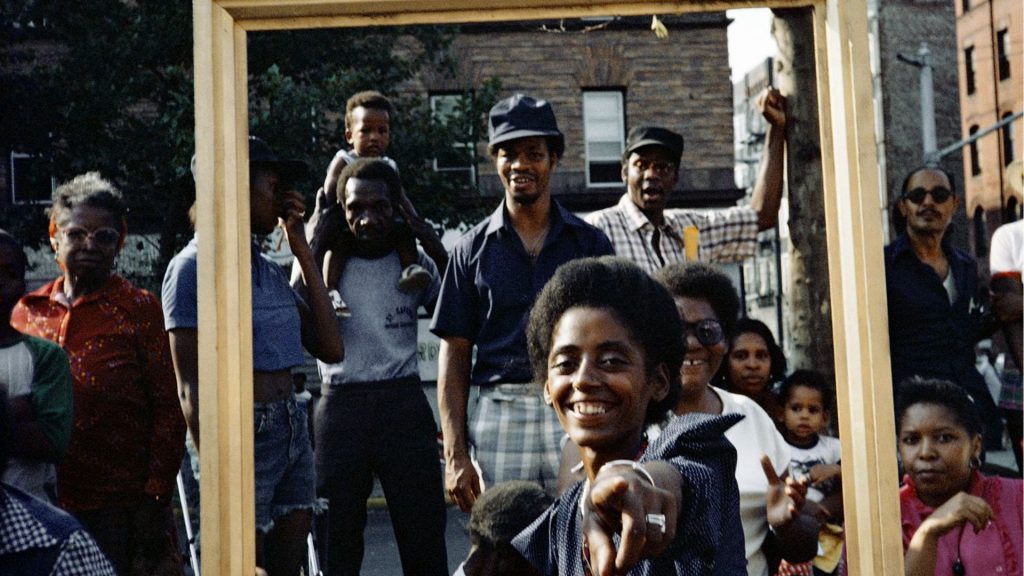

Across the pond in the US, programming in major art institutions reflects a continuing investment in social justice movements and radical feminist politics. Currently on show at the Brooklyn Museum in New York (home to Judy Chicago’s legendary feminist art installation The Dinner Party) is ‘Both/and’ the first-ever retrospective of the leading feminist performance and conceptual artist Lorraine O’Grady

O’Grady is known for her trenchant critique of Blackness within western modernism. In the 1980s the artist infiltrated art events as her fictional persona ‘Mlle Bourgeoise Noire’ (Miss Black Middle Class), a tempestuous beauty queen dressed in a costume made from 180 white gloves and brandishing a cat o’ nine tails studded with chrysanthemums (a reference to the whips used against enslaved people on plantations).

These guerrilla performances asked questions of the way in which Black art in that period was being moulded into a tame and polite discourse that would fit comfortably into the predominantly white art world. Also widely regarded as an art critic, O’ Grady published the first-ever essay of cultural criticism about the black female body in 1994 with her analysis of the often overlooked black maid in the French artist Edouard Manet’s famous 1865 painting Olympia.

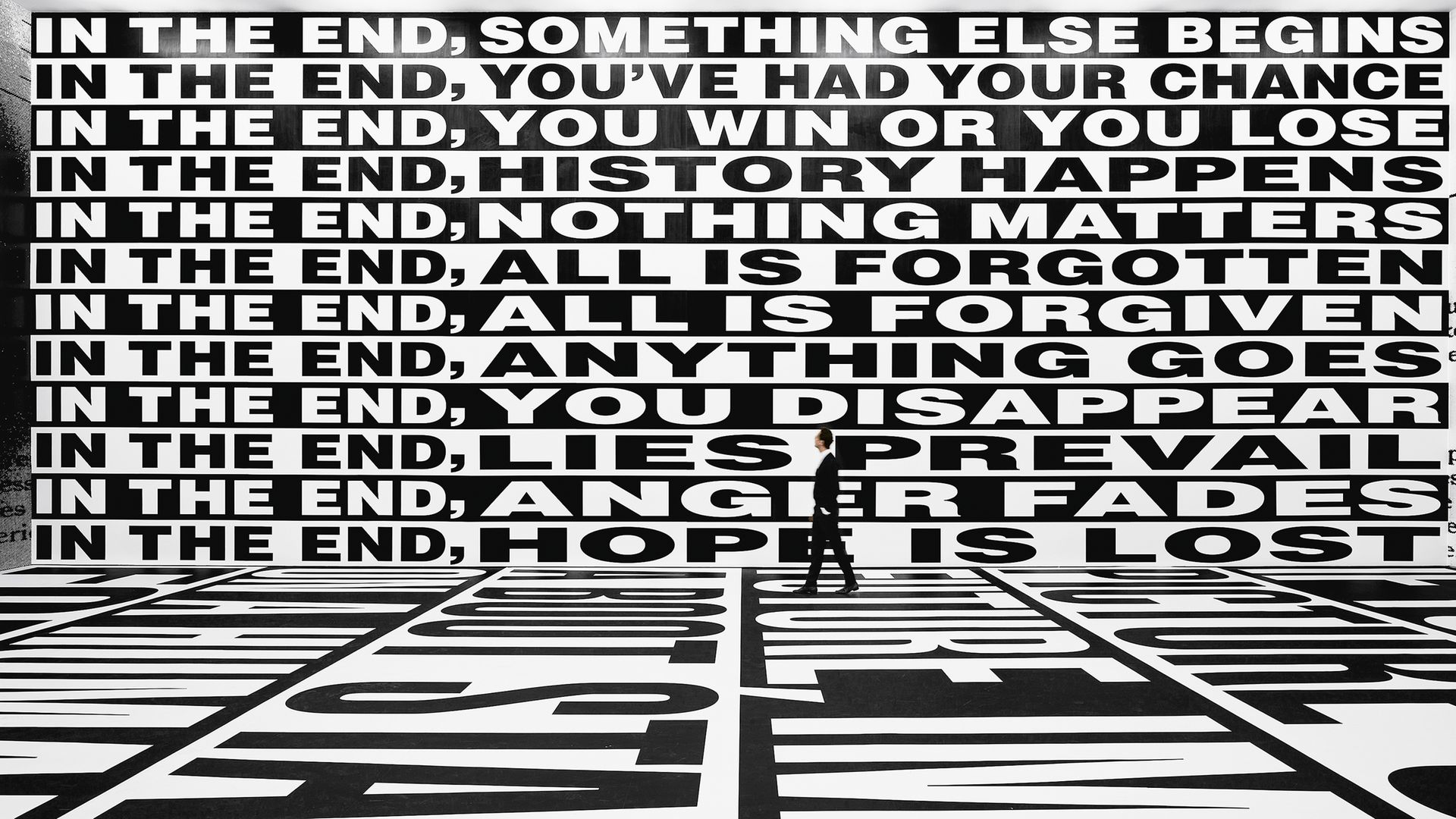

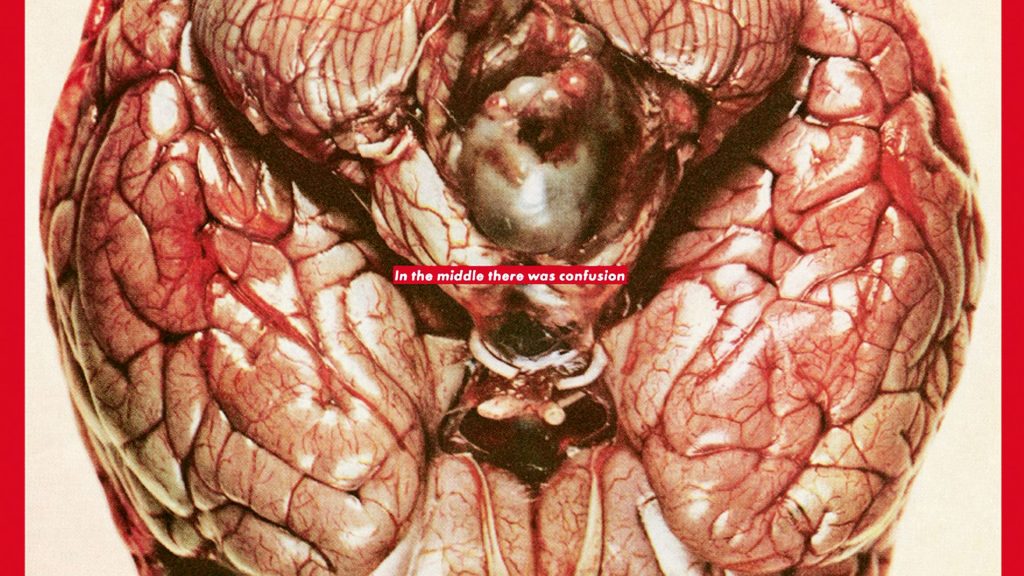

Barbara Kruger, another second-wave feminist American artist has a survey opening at the Art Institute of Chicago (September 2021-January 2022). Designed and curated in collaboration with the artist ‘Thinking of You, I Mean Me, I Mean You’ promises to upend the traditional format of the artist retrospective with something characteristically fresh and provocative.

The exhibition includes four decades of Kruger’s incisive interrogation of gender, identity capitalism, consumerism, and shows the evolution from her analogue ‘paste ups’ from the 1980s to her embrace of digital era image-making.

Inspired by the philosophical study of signs and language by philosophers such as Roland Barthes and Walter Benjamin, Kruger came to prominence for her interruptive posters in the late 1970s and 1980s that borrowed from the language of advertising to subvert entrenched ideas about women’s happiness and consumerism with works such as I shop therefore I am. The show will also overspill the boundaries of the museum, with works appearing on billboards and buses across Chicago.

While we might no longer need to argue for the existence of ‘great women artists’ as more than just a handful of female artists become visible in public institutions, there remains much more to be done to change the structure of whose art and whose vision we’ve been taught to value.

As our engagement with culture beyond screens slowly becomes a possibility once more, we could all benefit from more diverse perspectives to make sense of the troubling personal, social and political realities of our current moment.

Catherine McCormack is the author of Women in the Picture: Women, Art and the Power of Looking (Icon books, £12.99 hardback)

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37