Françoise Hardy helped create French youth culture. Now, as she nears death, she is starting a new national debate about ageing and euthanasia

Françoise Hardy’s son would like it to be known that his mother – a pillar and adornment of French pop music for almost 60 years – is still alive.

A few days ago, Hardy, 77, announced that she was “near the end” and called for the legalisation of euthanasia in France. Last weekend, a French regional newspaper announced that she had died. One million people signed a virtual book of condolences on Facebook – prematurely.

Her son, Thomas Dutronc, issued a statement, half angry, half jokey, in which he said “My mum is not dead. I just talked to her on the phone. All is not great for her… She had a problem closing her fridge. A packet of frozen vegetables is in a bad way and there’s a pool of water on the floor.”

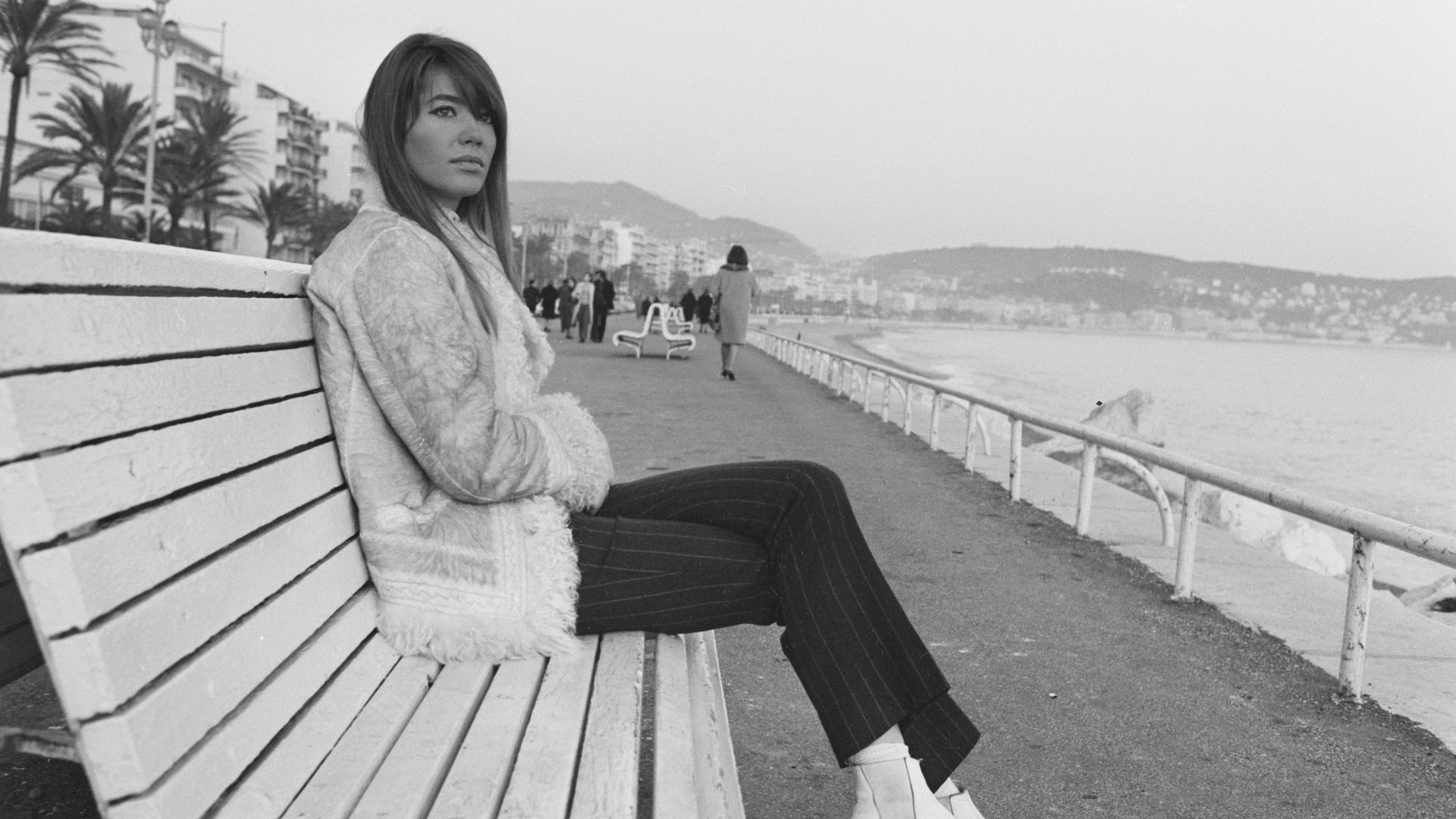

Anyone who recalls the British pop boom of the 1960s will remember Françoise Hardy. She was the only foreign pop star, other than Americans, to invade the British music charts in the midst of Beatlemania and Stonesfrenzy.

In the early 1960s, you never – more is the pity – got to see Johnny Hallyday, the greatest of all French rockers, on Top of the Pops or Ready Steady Go. You did see Françoise Hardy, who had the figure and cheek-bones of a model and sung softly in a melancholic and sexy and (we assumed) very French way.

She fascinated the young David Bowie. Mick Jagger said that he was his “ideal woman”. Bob Dylan wrote a poem about her.

Hardy went on to record 30 albums, sell 7.6 million records, make films and write novels and other books. She has been ill, on an off with lymphatic cancer for 15 years but she made an excellent album – melancholic as ever – only three years ago.

When she started her career in 1962, she was 17. Edith Piaf, the greatest female exponent of the French style in popular music – la Chanson Française – was still alive. In fact, Piaf’s best remembered song, Non, Je ne Regrette Rien, was recorded in 1960, only two years before Françoise Hardy’s first hit.

Hardy wrote Tous les garçons et les filles (‘All the Boys and Girls‘) in her mother’s kitchen after teaching herself to play three chords on her guitar. The difference between the two songs tells much of what you need to know about an era when French popular music was being strongly influenced – some thought polluted – by American and British influences for the first time.

Piaf’s song is the triumphant, soaring, poetic anthem of a mature woman looking back on a difficult life. Hardy’s is an Everly Brothers pastiche, the cheerful-mournful thoughts of a teenage girl without a boyfriend.

In 1962 French pop music was in the process of being conquered not just by Anglo-Saxon styles but by the spending power and new-found independence of youth. Some of the youths, like Johnny Hallyday and Eddie Mitchell and Françoise Hardy, remained popular for the next half century.

The period is known in French, or Franglais as the yé-yé era – a title invented by the great French philosopher Edgar Morin after he listened, frowning probably, to a TV interview in which Françoise Hardy explained the lyrics of The Beatles hit, She Loves You (…”yeah, yeah, yeah”).

Hardy is her a real name, a common Norman surname – not an Anglicised rockbiz name like those of Johnny Hallyday (Jean-Philippe Smet) or Eddie Mitchell (Claude Moine). Françoise Hardy is doubtless distantly related to the English novelist and poet Thomas Hardy or to Captain Thomas Masterman Hardy of HMS Victory.

Though a model and actress as well as a singer-song-writer, Françoise Hardy never behaved like, or thought of herself as, a star. She has spoken in two biographies of her constant anxiety and her sense of always having been an impostor.

She told Le Monde in a very frank interview in 2018: “I always felt ashamed of myself, ashamed of my background, ashamed that I came from an atypical family.”

Her mother had two daughters with a married man who took little interest in his second family except to insist that the girls attend very conservative, Catholic convent school (whose fees he often omitted to pay).

Françoise discovered British and American pop music listening to Radio Luxembourg under her bed-covers at night in her mother’s tiny flat in the 9th arrondissement of Paris. Her father bought her a guitar for her 16th birthday. She began to write her own songs – and continued to do so all of her life.

Her biggest success outside France was a wonderfully sad song in English – All over the World – which spent 15 weeks in the UK top 20 in 1965. Many of her later songs (like some of Johnny Hallyday’s) are much closer to the French popular musical tradition than to British or American pop or rock.

Hardy was married in 1981 to the French pop singer Jacques Dutronc. They had already been a couple for 14 years and remained close friends after their separation. Their only child, Thomas, is also a French pop singer.

Last week Hardy told the magazine Femme Actuelle in an e-mail interview that she had a tumour in her ear after years of fighting lymphatic cancer. Repeated radiation treatment and immunotherapy had caused her great pain and made it difficult for her to swallow.

She said – not for the first time – that she wished that France allowed euthanasia.

“It is not for the doctors to accede to each request,” she said. “But to shorten the unnecessary suffering of an incurable disease from the moment it becomes unbearable.”

In April she had already complained to France Info radio that she thought France’s ban on euthanasia – despite tentative legislative moves in recent months to ease the “end of life” – was “inhuman”.

She revealed that she had “collaborated” with a hospital doctor to shorten her mother’s life when she as suffering from a “horrible incurable disease”.

“When something is incurable, it is inhuman not to shorten suffering,” she said.

“I would love to be given the same chance but given the fact that I’m somewhat well known, no doctor would want to risk being struck off by helping me.”

Nonetheless her son implied at the weekend that his mother was still full of querulous, but no doubt melancholy, life.

Hardy’s finest song of recent years, recorded in 2018, was Le Large (‘the open sea’) in which an elderly woman looks back on her life and reassures a young boy that “all will be fine” after she departs.

The song might have been called: “Non, je ne regrette rien.”

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37