In the 1970s, Italian film-makers forgot spaghetti westerns and made Poliziotteschi – violent detective thrillers that echoed the likes of Dirty Harry.., and their own crisis at home

Here is a hypothesis for you: if you’re looking for art that explains the mood of times past, you should look not at the acclaimed, serious-minded and considered pieces but instead head downmarket. The big-brained stuff might provide context and even speak of wider truths but it lacks the immediacy and impact of pulp. Driven by financial imperatives that prioritise a ripped-from-the-headlines immediacy, topical trash better captures the contemporary mood than more reflective highbrow stuff.

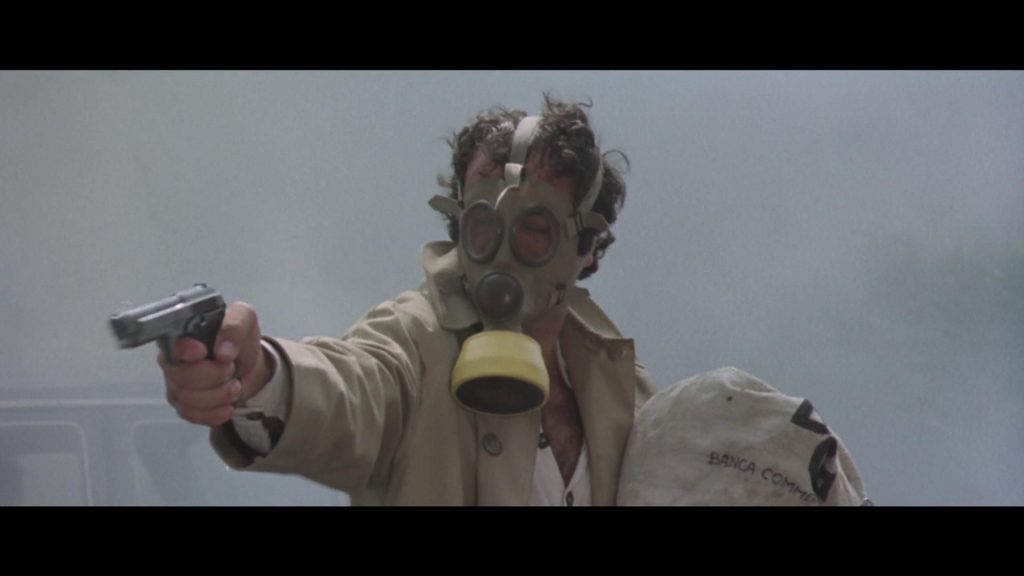

This thought is prompted by a new blu-ray box-set released by genre maestros Arrow Films. Entitled Years of Lead, it offers a five-film survey of crime movies made in Italy during the 1970s. It’s a welcome package, and not simply because the films included are so worthwhile; it shines a light on a style of film that’s been under-appreciated for far too long.

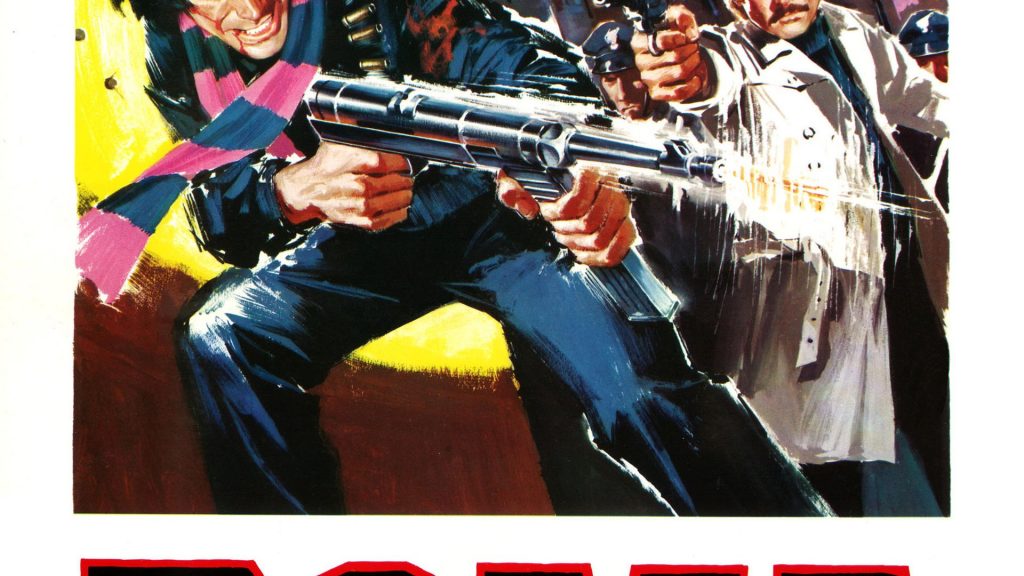

Like many Italian genre films, the Poliziotteschi – as these tough tales of law and disorder are known – was inspired by American product, in this case, the hard-nosed cop movies that superseded traditional cowboy flicks in the late 1960s and early 1970s – Dirty Harry, The French Connection, that sort of thing.

But what has always made Italian rip-offs so endlessly fascinating is that Italian filmmakers aren’t actually particularly good at copying. They may borrow the trappings – in this case, maverick detectives with a no-nonsense attitude that rubs those god-damn pen-pushers at City Hall up the wrong way – but they use them to very different, very distinctive, ends.

The Poliziotteschi was animated by many of the same concerns as their American inspirations: crime was reckoned to be going up in both countries, exacerbated by a (perceived) explosion of drug abuse. Of course, the homeland of the cosa nostra had always had its fair share of bad behaviour, but that had previously been concentrated on the impoverished south: now it was infecting the affluent north too.

The 1970s were a grim time for a great many nations: older Britons still shudder at the thought of the three-day week and winter of discontent, not to mention the IRA blasting everything to kingdom come. But Italy had things worse and the Poliziotteschi can be seen as a psychic safety valve.

Take, for instance, the film Killer Cop (La polizia ha le mani legate, 1975). It begins with an explosion at a hotel, the work, or so it appears, of student radicals. Italian audiences of the time wouldn’t have needed much prompting to recognise the parallels to a real bombing from 1969 at a bank on the Piazza Fontana in Milan, in which 16 people died. The link is later made more explicit when a key suspect is pushed (sorry, ‘falls’) from a window, something that also happened to a key suspect in the real bombing, then in detention at a police station. (This event also inspired Dario Fo’s Accidental Death of an Anarchist (1970), a more seminal work, but one with inferior action scenes.)

The Piazza Fontana bombing is generally taken as the start of what became known as the Anni di piombo (‘years of lead’, per the boxset), named for the number of bullets flying. A few of those were fired by the mafia but, for once, they played mainly a supporting role. Ordinary freelance criminals were more active, and more violent. Bad as all that was, it was made much worse by political violence of all stripes – while anarchists initially copped the blame for the Piazza Fontana, it was later established the far-right had done the job. It was darkly intimated that they had been shielded by forces within the political establishment (alluded to in Killer Cop): this was a boom time for outlandish conspiracy theories (‘dietrologia’ – ‘behind-ology’ – as the Italians put it, as in ‘who’s behind this?’). Not all of them have been disproved.

The most notorious criminal faction of those days were the Brigate Rosse – the Red Brigades, an amorphous group of Marxist malcontents who perfected the art of criminal theatre, with set-piece bombings, kidnappings and murder; few terrorists have sown terror so effectively. Curiously, the Poliziotteschi seldom addressed the Red Brigades directly, although the number of bombs in these films – significantly more than feature in action films from other nations made during the same decade – can be taken as oblique comment on them and their equally explosive far-right equivalents.

The genre was rather more attentive to other crimes, though. One recurrent (very nearly ubiquitous, in fact) feature of the Poliziotteschi is kidnapping; in Italy at Gunpoint (1976) it’s a bus full of school kids, in Free Hand for a Tough Cop (Il trucido e lo sbirro, 1976), it’s the seriously ill daughter of a plutocrat and these are far from the only examples.

This was horribly topical. The 1970s saw an epidemic of kidnapping in Italy, with hundreds – some have claimed thousands – of cases (not every such crime was reported to the authorities). Some of these were the Brigate Rosse’s doing: their targets included industrialists, bureaucrats and judges – anyone they considered to be part of the establishment was a target. Mostly, though, kidnapping was about greed than ideology, although it wasn’t just the wealthy who were at risk – prudent working class families who’d put a bit of money away were considered fair game too. It was, then, a universal fear; at least in Poliziotteschi the villains were always punished.

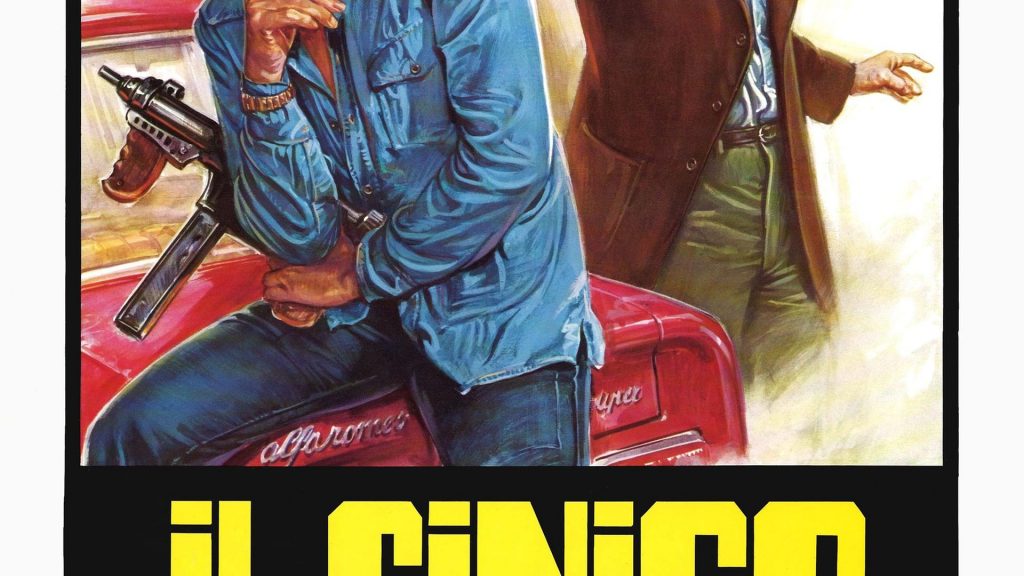

Another Poliziotteschi perennial was the depraved rich kid, usually hunting in packs and terrorising those less advantaged as themselves. You can find examples in The Savage Three (Fango bollente, 1975) (included in the new boxset); in Rome Armed To The Teeth (Roma a Mano Armata, 1976); The Cynic, the Rat and the Fist (Il cinico, l’infame, il violento, 1977) and a great many others. This is not just down to the universal dislike of Bullingdon Club-types but reflects on a very real crime, the so-called Circeo Massacre of 1975, in which four upper-class youths imprisoned two young women; one died after two days of abuse. The other survived only because she played dead.

One of the films in the box-set tackles this nightmare more directly, with a title reflects how Italians considered the perpetrators: Like Rabid Dogs (Come cani arrabbiati, 1976). This movie, and the sheer number of other films that allude less directly to the crime, illustrate just how badly it traumatised the country, not simply an abhorrent crime but a veritable symbol of morality’s decline. While there’s an element of catharsis in the films – the hero can administer the kicking everyone else dreamt of doing– there’s also a desperate puzzlement, an attempt to understand how people could do such a thing.

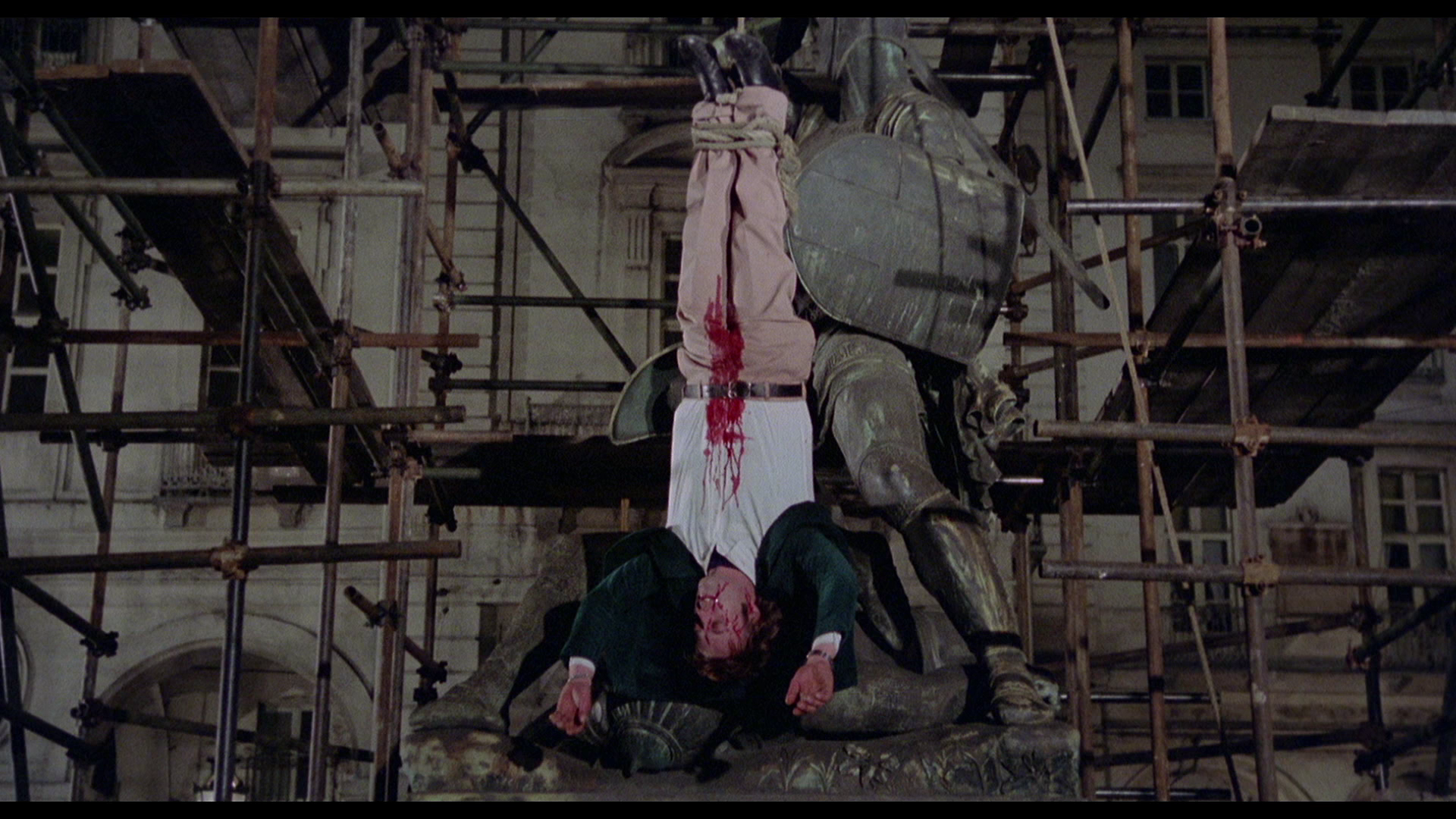

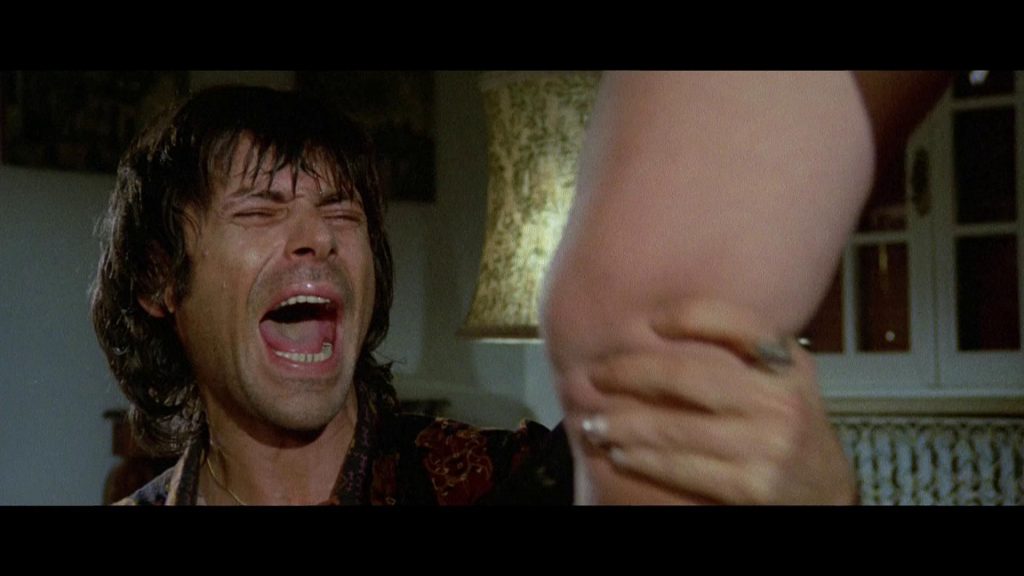

That’s true of the Poliziotteschi more generally, with films trying to comprehend the mentality of the new criminal class. Almost Human (Milano odia: la polizia non può sparare, 1974) is one of the very best Poliziotteschi, in large part because of its star, Tomas Milian. He tears into the role of Giulio Sacchi, a man who might look like a member of a minor Britpop band but has something of the devil about him. Alternating self-pity with alarming psychosis, he terrorises ordinary folk, kidnaps a child (obviously; it’s a Poliziottescho) and murders his girlfriend. Italian filmmakers had specialised in baroque villains at least since the Spaghetti Westerns but Poliziotteschi placed them centre-stage, avatars for the unfathomable new breed of criminals, from the Red Brigades on down.

These are not sophisticated films and indeed, that’s all part of their charm. Not everyone, however, was impressed. As with their American forebears, Poliziotteschi often got it in the neck from the critics but the stakes were higher in Italy. When Dirty Harry and its kin were labelled ‘fascist’ in the US, most people took that as hyperbole. When the same term was applied to Poliziotteschi in their homeland, it was a rather graver charge.

At the start of Killer Cop, some bus passengers discuss the latest atrocity and conclude that they need stronger government. Someone then comments, rather wistfully, “we had strong government for 20 years…” Even 30 years after Mussolini had been strung up from the lamppost, Fascism still had not inconsiderable support in Italy; the extraordinary San Babila 8PM (1976) – another film based on an infamous real-life crime – focusses on teenage blackshirts, to whose activities the authorities seem to turn a blind eye.

At first sight, Poliziotteschi seem to be right-wing wish fulfilment, filled as they are with the sort of robust policing of which our present Home Secretary would doubtless approve. That strand cannot be denied but there is often uneasiness too. One of the stand-out films in the Years of Lead set is Colt .38 Special Squad (Banda del Gobbo, 1975), in which the police abandon the rule book with less than happy consequences.

Even more cavalier are the heroes of Live Like A Cop, Die Like A Man (Uomini si nasce poliziotti si muore, 1975). They are quite possibly the most obnoxious lawmen in cinematic history, and frequently resort to outright criminal behaviour while on the beat. That’s either horrifyingly crass, or an indictment of a laissez-faire justice system that gives impunity to hooligans as long as they’re brandishing a police badge.

Even if Poliziotteschi leant to the right, there were those who tried to shift the centre of gravity; the Italian film industry was, after all, filled with lefties and they were always keen to undertake a small detour in the plot to take a pop at the bourgeoisie. The best example is probably in Brothers Til We Die (Banda Del Gobbo, 1977), which again stars Tomas Milian, this time playing a villainous hunchback; ‘Il Gobbo’ rolls up at a high-end nightclub with his gang and encourages the wealthy patrons to laugh at his misshapen form. Whereupon he has them tied up, robs them and then – ahem – feeds them laxatives.

And there was scope to get more political still: the excellent, and thoroughly cynical, Goodbye & Amen (1978) begins with the head of the CIA in Rome arranging a coup d’etat in an unnamed African country but his planning is interrupted when one of his underlings apparently goes on a killing spree: ‘crime’ is only a matter of scale.

Italian genre films had a finite shelf-life and, as with the Western before it, audiences eventually tired of Poliziotteschi. By the end of the 1970s, new styles of filmmaking elbowed them aside at the box-office. It would nice to say that this change coincided with an outbreak of peace but if anything, things were getting worse: a bomb at the Bologna station took 85 lives in 1980; 17 more were lost when a bomb went off on a Rome-bound train in 1984. The kidnappings continued, the Red Brigades were still active and then the Mafia decided to have a civil war (and what is a civil war without civilian casualties?).

So perhaps it is significant that horror became the next big thing in genre filmmaking, and not just ordinary horror but the most brutal, gut-wrenching (literally…) variety imaginable, often made by Poliziotteschi veterans. Ruggero Deodato (Live Like a Cop, Die Like A Man) made the notoriously nauseating (if undeniably potent) Cannibal Holocaust (1980), to which Umberto Lenzi (Almost Human) responded with the notoriously even-more-nauseating Cannibal Ferox (1981).

Both were branded, accurately, ‘video nasties’ when they arrived on VHS in the UK but the notion of human beings committing atrocities on one another then feasting on the remains is not the worse metaphor for what was being described on the nightly news.

There was no decisive end to the ‘years of lead’ – the Red Brigades remained semi-active even into the 1990s – but things calmed down by the mid-1980s, enough for some level of normality to resume thereafter, even if the memories remained – remain – traumatic.

Like so many communal nightmares, it has often been revisited since, through art, through books, television and, yes, film production. Much of this is no doubt objectively ‘better’ than most of the Poliziotteschi cycle, but it is work made from a safe distance, with the certainty that comes from hindsight. The rough-hewn films found in the new box-set and elsewhere don’t have that luxury and that is their strength; they show what it’s like to live in a country under siege, and so help understand the scars that leaves.

Years of Lead is released by Arrow on June 28th. Rome Armed To The Teeth will be released as The Tough Ones by 88 films in July.

A STAR IS BORN…

Lacking the resources of Hollywood, Italian filmmakers routinely cut corners to get results: car chases were usually filmed on real roads, getting around the tedious obligation to acquire ‘permission’ by shooting in the wee small hours before rush hour.

And if they couldn’t afford a star, why they’d find an alternative: when Franco Nero proved too expensive, the producers of Violent Rome (1975) hired bit-part player Maurizio Merli, whose main qualification was that he looked a bit like Franco Nero. Audiences didn’t mind; Merli subsequently became a star in his own right. Bigger than Nero, in fact!

…AND A POLITICIAN IS KILLED

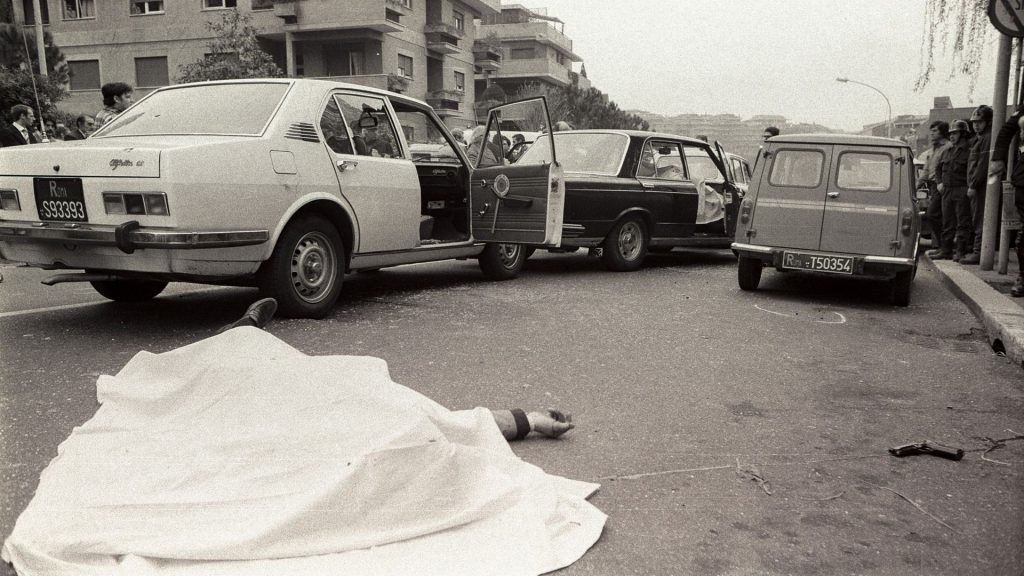

Italy’s greatest post-war crisis came in 1978, when a direct assault was mounted on the system of government. Aldo Moro was then-president of the country’s Christian Democrats and a widely admired former prime minister; he was responsible for the famous ‘historic compromise’ of 1976, which allowed members of the Italian Communist Party (PCI) to take positions in government for the first time.

This was anathema to the Red Brigades who believed in violent revolution rather than parliamentary democracy. For that, for his symbolic status and also because he had a lighter security detail than prime minister Giulio Andreotti, they chose to kidnap him, killing five of his bodyguards in the process. After 55 days, on the 9th of May, his body was found in the boot of a Renault 4 parked in the middle of Rome.

Too raw even for Poliziotteschi producers, it took time for the Moro kidnapping to make it into cinemas, and even then it was played as sober drama; the best account is Buongiorno Notte (2003), which tells the story from the viewpoint of one of his captors, a woman who starts to have doubts about her mission.

What do you think? Have your say on this and more by emailing letters@theneweuropean.co.uk

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37