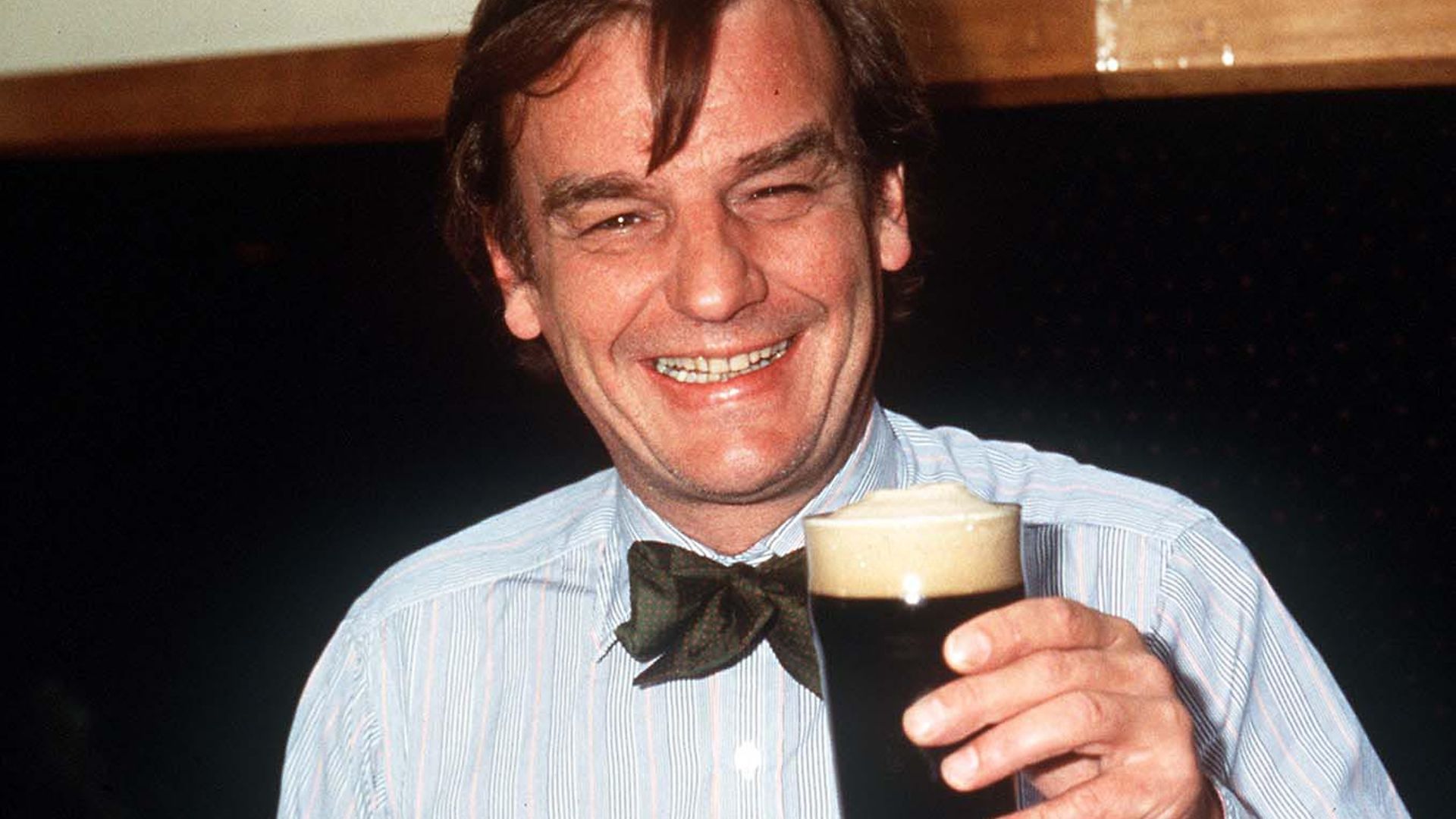

Keith Floyd’s charm turned him into a caricature. SOPHIA DEBOICK thinks that, instead, he should be remembered as the nation’s culinary pioneer

“Pick young, small, un-flowering dandelion leaves. Wash and dry them carefully. Serve with olive oil, salt and sherry vinegar and cubes of hot fried bread.” This was the delicious simplicity of Floyd’s Food, Keith Floyd’s debut cookbook, published 40 years ago this year.

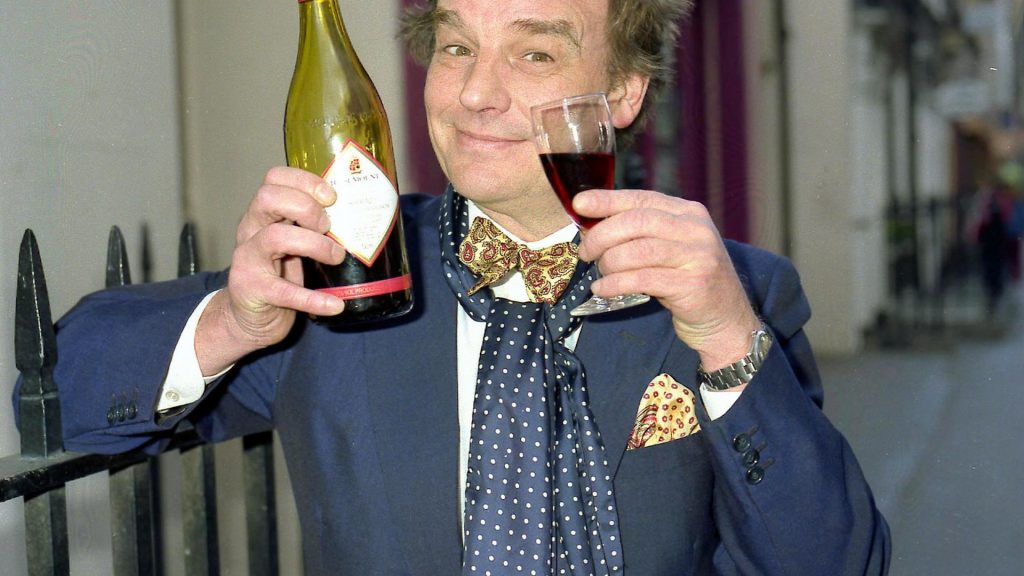

The culmination of two tumultuous decades in the restaurant trade, the book marked the beginning of a career as a public figure during which Floyd would write nearly 30 more cookbooks and become one of television’s biggest personalities. So big, in fact, that for many he is remembered as the boozy caricature parodied by Spitting Image and Rory Bremner, and not as the pioneer who revolutionised not only our view of food, but of Europe itself.

The son of a working class family raised in a Somerset village, Floyd won a scholarship to Wellington School and began to develop a taste for the finer things in life, as well as an inferiority complex (“The other boys at Wellington wore smart uniforms, while my clothes were made by my mother,” he wrote).

But it wasn’t until he became a trainee reporter on the Bristol Evening Post and Western Daily Press that Floyd encountered the kind of food that embodied the high life that he spent his life pursuing.

It was 1959. Floyd, who had been raised on rabbit, tripe and faggots, recalled in his autobiography Stirred But Not Shaken (Pan, 2009) that at that time in Britain “food was nothing more than a commodity… Garlic? Forget it.” Everything changed when his editor took him to lunch at maverick cook George Perry-Smith’s Hole in the Wall restaurant in Bath.

A 16-year-old Floyd ate partridge with cabbage, Gewürztraminer and juniper, pommes dauphinoises and chocolat Saint-Emilion. It was a culinary epiphany, and when he asked Perry-Smith where such ideas came from, he replied, “Oh, quite simple, dear boy. Just read Elizabeth David.”

David’s debut, A Book of Mediterranean Food, had appeared in 1950, and the classic French Country Cooking came the following year. The result of her travels in Europe, her books presented an approach to food that was nothing less than revolutionary in Austerity Britain, using ingredients ubiquitous today, but far from kitchen staples then: olive oil, citrus fruit, Mediterranean vegetables, fresh herbs, wine and, of course, garlic. When Floyd ditched journalism for the army, joining the Royal Tank Regiment and being posted to Germany, he turned to David (“my all-time heroine”) in an effort to improve the appalling food served in the mess.

Floyd showed the mess cook, who he swore was genuinely called Corporal Feast, how to make David’s terrine de lièvre using the abundant local hare. In return, Feast drilled Floyd in the basics of kitchen craft, including how to use a sharp knife properly. This was Floyd’s initiation into the sweat and adrenaline of the professional kitchen.

After discharge from the army following a nervous breakdown, Floyd wasted no time in presenting himself at Bristol’s Royal Hotel for a kitchen job. There, amid the brigade of sous chefs “burning things and killing things”, he found at long last that the kitchen was where he belonged.

In 1967 Floyd began running Bistro Ten in Bristol’s trendy Clifton district, a place of jazz and folk clubs and eateries with continental pretensions, and he turned the former coffee bar into a place that served boeuf bourguignon, stroganoff, and scallops wrapped in bacon.

It was a revolutionary year for the British restaurant scene. The Roux brothers opened Le Gavroche, setting the standard for French gastronomy on British soil. Peter Boizot opened his second Pizza Express restaurant, bringing simple, authentic European food to London. Floyd was 25 and the atmosphere was ripe for anyone with ambition as a restaurateur. Two years later, opened his first restaurant of his own.

With Toulouse Lautrec posters on the walls, gingham tablecloths, a “lethal Moroccan red” served by the litre and the Stones and the Kinks blasting out, Floyd’s Bistro was the embodiment of its proprietor’s philosophy of food being principally about having a good time. The menu stayed true to the formula of Elizabeth David via George Perry-Smith, while Floyd’s Restaurant, one of two further venues he opened in Bristol soon after, aimed for greater refinement: shellfish and game, Taittinger as the house champagne, caviar and Stolichnaya at the bar, Havana cigars and Ella Fitzgerald.

But however inspired he was as a restaurateur, Floyd was no businessman, and at 30 he sold his restaurants in financially unfavourable deals and left Bristol, leaving his wife and young son behind to sail around the Mediterranean on a yacht for 18 months. It was an attitude to his marriages (four in total) and his children to be repeated down the years.

Discovering Mediterranean food first-hand on his voyage and immersing himself in French culinary tradition by opening a tiny restaurant in the Provençal town of L’Isle-sur-la-Sorgue changed Floyd’s style of cooking, and when he returned to Bristol to open a new, open kitchen restaurant, his food was simpler and fresher than the stonking classics he had pursued before. It was this sort of cooking Floyd’s Food put in print, and it was at this restaurant that one customer, David Pritchard of BBC Bristol, watched the cook at work and spotted a star. “How would you like to be on television?” Pritchard asked.

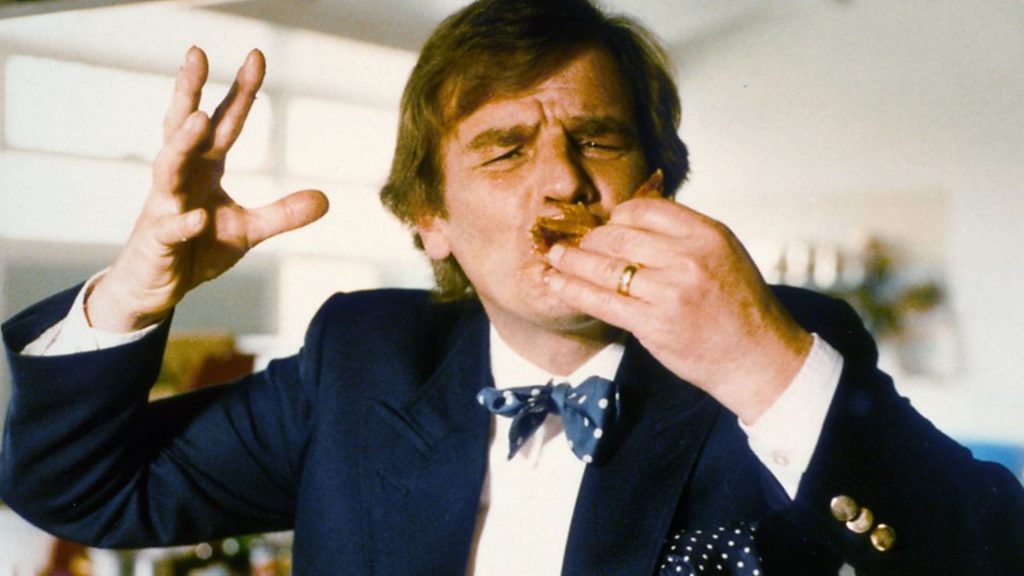

Floyd’s inimitable TV style happened far more by accident than design, emerging fully formed on his and Pritchard’s first series together, Floyd on Fish (1985). Pritchard’s chaotic approach to production meant unscripted improvisation, cooking outdoors, wobbly hand-held camerawork and the compelling spectacle of the cook under extreme pressure. Floyd proved himself equal to it, irreverent, amusing and always irascible with long-suffering cameraman Clive North. Nothing so anarchic had been seen on TV before.

Floyd would later observe that the food programmes of the time “were dull and worthy and akin to a secondary school lesson in modern home economy”, and not without good reason. Delia Smith’s One is Fun!, focussing on dishes for the single cook, was the other big food series of 1985 and found a studio-bound Smith detailing every weight, measure, step and timing at glacial pace (her pizza for one recipe specified precisely six anchovies and six olives). Floyd instead embraced the philosophy of chucking everything in, only begrudgingly giving timings for those viewers “who can’t afford a cookbook and really insist on knowing how long things take to cook”.

But it was 1987’s Floyd on France that was Floyd’s finest hour. Despite some claims to the contrary, he did not single-handedly introduce the British viewing public to French food – Fanny Craddock, for one, had been singing the praises of Escoffier, albeit through a very British suburban lens, on our television sets since the 1950s. But Floyd on France was far more than just a cooking programme.

In Floyd on France, food was a conduit to a nation’s culture, if not its soul, and the series was about people, places and produce as much as specific recipes. Indeed, while Floyd’s passion for the food was palpable, the actual cooking was often cursory, and instead he brought France itself to British television screens in a way never done before.

The idealisation of France, particularly its south, as the ultimate British middle-class dream would be crystalised with the success of A Year in Provence in the early 1990s, but the persistence of a decades-long stereotypical view of the French in the 1980s was suggested by ‘Allo ‘Allo getting 14 million viewers a week, while The Sun’s “Up Yours Delors” front page of a little later didn’t waste the opportunity to mention smelly cheese, Waterloo, and surrendering to the Nazis.

Floyd’s series had no room for cliches about our continental neighbours, instead showing the complexity of the real France, from the varied traditions of its different regions, to its culinary heritage of unplumbable depth.

But Floyd also created a new paradigm for food on television through Floyd on France. This was the food programme as travelogue, where the cook encountered the locals, pawed the wares at the markets, and marvelled at the landscapes. It is a formula that has been repeated ever since, not just by David Pritchard’s other protégé, Rick Stein, but so many more.

But, as done by Floyd on Floyd on France – a kind of cross between Alan Whicker and the dissolute title character of Withnail & I, the film of the same year as the series – it has never been bettered.

For the viewer at home, Floyd on France made food undaunting. Floyd’s culinary limitations were obvious, and if he could do it, so could we. He was often seen taking direction from stony-faced old-school chefs or no-nonsense French housewives.

When his attempt at a Basque piperade was savagely criticised by a formidable Biarritz matriarch, he happily conceded it was “heavy, lumpy, nasty, British Rail style scrambled eggs” compared to her effort. He was apparently without ego and it’s difficult to imagine the laddish swagger of a Jamie Oliver or the testosterone-fuelled aggression of a Gordon Ramsay accommodating such graciousness.

“My approach, my attitude?”, he later wrote, “It was: I don’t know anything at all. And the way you find out about things is to say, ‘Excuse me, what, why, where, when and how did you do that?’”

It was perhaps this curiosity about other cultures, explored further in series on Spain, Italy, Scandinavia, Australia, the US, Africa and India, that was Floyd’s greatest contribution to our national life.

He was not always an attractive character. Few alcoholics are. But for all his flaws, Floyd introduced us to a world beyond this island, a world to be explored and asked questions about, and where simple culinary pleasures were made to be shared.

Floyd on France is available on BBC iPlayer

KEITH FLOYD’S PIPERADE

Serves 4

This is not scrambled eggs with peppers and tomatoes, it’s a sauté of vegetables into which eggs are beaten, and the Basque people are very particular about it. They argue amongst themselves as to whether you should use the hot pimentos from Espellette or simple red or green peppers. The best compromise is to use red and green peppers and then spice up the whole thing with a pinch of sweet paprika, because your chances of buying the piment d’espellette in this country are pretty remote. Anyway:

INGREDIENTS

Oil and butter for frying

2 red peppers, de-seeded and chopped

1 green pepper, de-seeded and chopped

4 ripe tomatoes, peeled, de-seeded and chopped

½ fresh red chilli (piment d’espellette) or a pinch of paprika

1 clove garlic, finely chopped

Thyme

1 bayleaf

Parsley

Salt and pepper

1 teaspoon caster sugar (the secret ingredient given to me by Mimi in Biarritz)

6 eggs

4 slices Bayonne or any cured ham (e.g., Parma), or good bacon

METHOD

In your favourite pan heat some oil and butter and cook all the vegetables, spices and seasonings with the sugar until they become mushy. Beat the eggs with a little water and stir them in as for scrambled eggs. Meanwhile, fry the slices of Bayonne ham and serve as an accompaniment to the Piperade.

(From Floyd On France, BBC Books 1987)

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37