From The Ladykillers to The Elephant Man, Jason Solomons celebrates some of the best movies set in London

When the pandemic stopped cinema in their tracks and the flow of new movies became an online trickle, many film fans took the time to look back and catch up on classics.

In the UK, one of the big successes of lockdown was a previously obscure TV channel called Talking Pictures TV which dug deep into the vaults of British studios such as Pinewood, Twickenham and Shepperton to bring viewers a diet of old-fashioned movies, invariably “in glorious black & white”. With thousands of workers stuck at home and furloughed, the appetite for matinee-style nostalgia grew exponentially and revealed a deep-seated affection for British film stars including Terry Thomas and Jack Warner, Michael Redgrave and James Mason, Dulcie Gray, Googie Withers and Valerie Hobson.

Lockdown grew the audience to three million viewers, which is no mean feat for a family business run out of a home in Hertfordshire. Although the channel played all day on screens in the UK’s care homes and reportedly sparked conversations and memories among the elderly, the audience was not restricted to the over-65s – a significant slice of viewers started to come from younger audiences keen to discover a somewhat neglected area of film history.

The taste for British film nostalgia is something French-owned media giant StudioCanal tapped into as they collected together their Vintage Classics series for remastering and restoring on DVD and Blu-Ray, repackaging a huge back catalogue of titles and bolstered by the acquisition of perhaps the most famous of all British film production lines: Ealing Studios.

Films such as The Lavender Hill Mob and The Ladykillers have long represented cornerstones of British cinema, with Alec Guinness marvellous in both, as he is in that other Ealing/Guinness tour de force, Kind Hearts and Coronets.

Many of these films occupy ‘national treasure’ status in the UK but that position has perhaps done them few favours over the years, something you watched with your grandparents on wet weekend afternoons on a small telly. A new appetite for vintage material, however, casts them in a new light.

“We get old but the art stays young,” says StudioCanal’s head of library John Rodden, neatly summing up the growing respect with which these old British treasures are now being treated and viewed. “That was our ethos from the start with the Vintage Classics,” he says, “to give these films the respect they are due – the artistry, craftsmanship, writing, acting, it’s all of the highest quality and the proof of that is in the endurance.”

Rodden’s task, when faced with a vast back catalogue, is one of curation, something that has become an increasingly crucial skill for the film viewer as much as the film programmer. We live now in a world of seemingly limitless choice, with every book, song and movie available at a click. How to make sense of such a place?

Faced with a box-set of over 200 titles, my own senses are sharpened by noticing the London-set films in particular, an array of films that chart life in the capital when it was very much a different place. As opposed to, say, the lottery-fuelled British film production boom of the late-90s, this vintage London is ruled by class, overshadowed by war, infused with Blitz spirit, rising out of the rubble, thrumming with wit and history and very much the backdrop to a new generation of talent.

This is like finding the Crown Jewels, a treasure trove of talents with which we can journey all around London. We can start south of the river, in Battersea, with The Lavender Hill Mob (1951) an undisputed British classic from the Ealing stable, with Alec Guinness and Stanley Holloway smelting down stolen gold bullion in the form of miniature souvenir Eiffel Towers. The film is notable for its slick script and particularly, for the fuss and bother of the trip to Paris, with customs and border controls – something we can all look forward to now. Again.

Typical of the Ealing ethos is the battle of the ordinary man against the perceived injustices of the system, which is usually class and wealth but also bureaucracy and, indeed, civility. Restrictions and expectations are fought in a slightly different Ealing production, as we move to the East End in It Always Rains on Sunday (1947), where Googie Withers’ Bethnal Green housewife is torn between her dull Sunday duties and the reappearance of an old flame (John McCallum) on the run from the police.

Shot by Douglas Slocombe, this is an East End noir and a revealing window on the bomb-scarred London creeping carefully and austerely out of the War, captured with a realism that practically documents life in a working-class street.

“The point is,” stresses Rodden, “a film like this is just as good as anything from Hollywood or France and I think British cinema has underplayed its quality over the years, perhaps because of some kind of an inferiority complex. The theatre was always considered the higher art form in Britain and cinema suffered from critical snobbery – but looking at these films again, that’s just blown away.”

One might add that, of course, you can’t look at theatre from the era. The plays might still exist in script form, but you can’t revive an Old Vic production and see Gielgud’s Hamlet, can you? The films, however, stay young.

If we stay in east London, by the 1960s, there was youthful vigour to the place, new tower blocks rising out of the bomb sites of Stepney and a new generation of working-class performers bringing authenticity to the screen. One of the leading proponents of this energy was Joan Littlewood and her Theatre Workshop based at the Theatre Royal in Stratford. Littlewood found success transferring a stage production of Sparrers Can’t Sing to the cinema, starring the late Barbara Windsor as Maggie, who has begun a new life in the long absence of her violent husband Charlie, who’s been away for two years’ at sea.

Given the title Sparrows Can’t Sing (1963) the film sits on the cusp of two eras, still humming with the language of a practically Dickensian London (Yiddish, cockney rhyming slang) but with a new morality, sexuality and feminism, as well as new architecture. In true East End spirit, the Krays hosted the film’s premiere in Mile End.

Charlie’s return from sea draws a direct line from Sparrows to Pool of London (1951), reminding current audiences of London’s primary importance as a port city. Set on the Thames and its wharves, on London Bridge and around St Paul’s, two sailors on shore leave get caught up in a jewel crime and a love story. Earl Cameron, who died last year, was one of the first black stars of post-War British film and his romance around London with white ticket seller Pat (Susan Shaw) is acknowledged as the first depiction of an inter-racial love story in British film. For modern audiences, this hopefully will not prove shocking – but the views of London depicted in the film certainly should, particularly the views from Greenwich out across the river and over to what are now the glass and steel towers of Canary Wharf.

“What you get when you watch these films is passion,” says Rodden. “I think there has long been a tendency to view these as something from your old Sunday afternoons on the telly but there’s nothing twee about them. They are exciting, stylish and shocking and they look very cool. It’s something that has been forgotten, or written out of film history. Hollywood and the French New Wave got all the cool kudos but it’s time British film was given that same respect.”

There’s nothing naff, for example, about Soho in the 60s. The Small World of Sammy Lee must be one of the coolest films of 1963, a gritty, sweaty, tense study of a strip-club compere played with neurotic energy by Anthony Newley. He plays Sammy, who owes £300 to a local bookie and the film follows him over a desperate few hours in which he tries every trick in his Soho chancer’s book to get some cash, including visiting his brother Lou (Warren Mitchell) and sister-in-law (Miriam Karlin) in their East End deli for a loan and a salt-beef sandwich. The against-the-clock action coincides with the arrival of a new girl (Julia Foster) who thinks Sammy’s invited her to live with him.

Directed by Ken Hughes and shot by Wolf Suschitzky, it brings a New Wave cool to the streets of Soho, many of which are still surprisingly recognisable, captured in a memorable opening montage set to a jazz score by Kenny Graham. The film was rather forgotten on release and flopped at the box office, falling between two audiences, those who were flocking to European arthouse by Godard, Fellini and Bergman, and those who began to prefer the colour productions of Hollywood and the star-stuffed UK comedies. The Small World of Sammy Lee is real gem of British cool, one whose sparkle still shines.

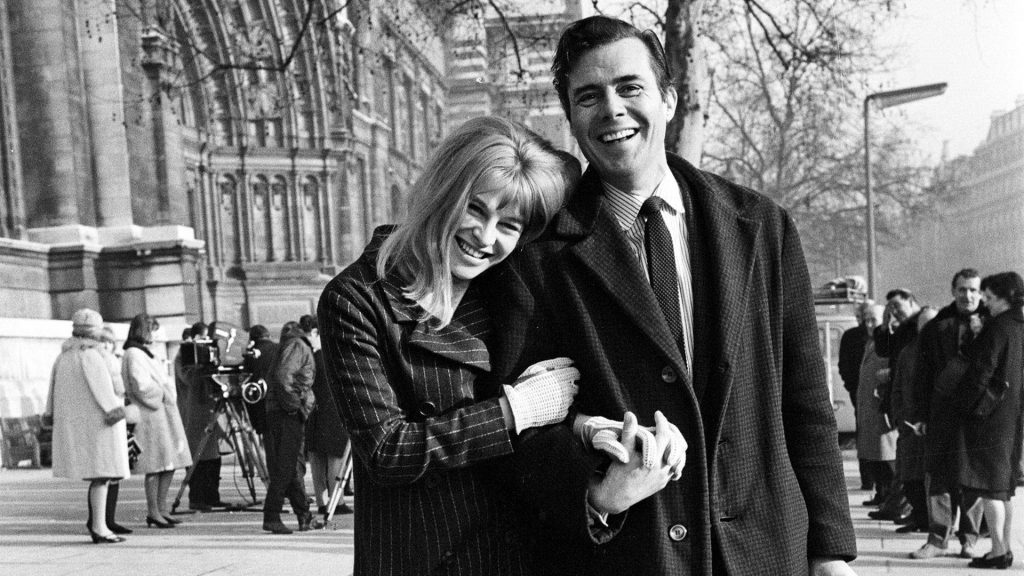

Far more successful yet also maintaining a Swinging Sixties cool is Julie Christie’s Oscar-winning turn in Darling (1965), a bold portrayal of a good-time girl, the so-called ‘freelance female’ exploiting the men in her life and her job and it’s one of the first media satires, set in a world of TV news, advertising execs and photographers.

Directed by John Schlesinger, its London landmarks take in the old BBC, Hampstead Heath, Shepherd’s Bush, Heathrow airport. I think Darling stands up as a monument to a time, its John Dankworth score still swings and there’s an appealing amorality to it, a refusal to judge its characters even if Darling herself ends up trapped by her own possibilities.

Less free to chose is Leslie Caron in The L-Shaped Room (1962) who plays an unmarried, pregnant French girl seeking refuge and breathing space in a Notting Hill boarding house. She strikes up relationships and friendships with the other residents, including Tom Bell’s struggling writer and gay, black jazz musician Brock Peters. With themes of abortion, race, duty and fidelity, directed by Bryan Forbes, The L-Shaped Room earned Caron an Oscar nomination and cements itself as part of the British New Wave and the kitchen-sink realism without ever feeling like a museum piece.

Its realism can be contrasted with the smart Belgravia environs of The Fallen Idol, starring another French screen legend, Michele Morgan who plays a typist at an Embassy who has an affair with the Ambassador’s butler, Baines, played by Ralph Richardson. However, it’s all told from the point of view of the Ambassador’s little boy Philipe who idolises Baines and can’t square his behaviour. Directed by Carol Reed and written by Graham Greene before they went on to collaborate on The Third Man, it also features the same Belgravia square Reed would later use for the house in Oliver! Although more classic in appearance than some of these British films, The Fallen Idol throbs with tension and suppressed passions and features a memorable scene set in London Zoo, all shot by the great French cinematographer Georges Perinal who also worked with Jean Cocteau, Rene Clair, Otto Preminger and Michael Powell.

“You can play artist association games with these films,” suggests Rodden. “You might admire Douglas Slocombe’s shot in one Ealing film and then you follow him and see what else he shot and that leads you to so many other movies, all the way up to Raiders of the Lost Ark and Rollerball. The standard of work in these films is of the very highest quality and should be recognised.”

Vintage as the material might be, there’s no hint of naffness around it anymore. One of the later works in the collection is The Elephant Man (1980), one of whose stars, Anthony Hopkins has just won an Oscar. It’s directed by David Lynch, which brings its connections with current cinema into perspective – shot in black and white by the great Freddie Francis (and produced by Mel Brooks), The Elephant Man remains a masterpiece of British film and of Victorian gothic yet, in its dignity and humanity, contains a streak of modernity, a fascination for science, architecture and attitudes. It feels somehow undated, as fresh as the day it was shot.

And that’s the point of classics, I feel. They reframe the present and give it context yet they also make sense of history and re-emphasise the artistry of the form, reminding us of the infinite variety of acting styles and of the elegance of perfect script writing. Such works can anchor our culture. It’s not all about newness and the latest, the next – after a year of pause and hiatus, these treasures from the past feel fresher than ever, no longer part of nostalgia but vital works that still have so much to say about our lives and our city.

What do you think? Have your say on this and more by emailing letters@theneweuropean.co.uk

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37