When Lili Alvarez took on Joan Lycett in the second round of the Wimbledon tennis championships in 1931 the talk should have been about whether this might be the year the Spanish player, who lost three consecutive Wimbledon women’s singles finals between 1926 and 1928, might finally lift the championship shield.

As the two women walked out in front of a packed Centre Court the buzz among the crowd was not about the quality of the tennis they were about to watch. It was about trousers.

Alvarez had a few weeks earlier reached the semi-finals of the French Open wearing what were effectively culottes, loose-fitting, calf-length trousers beneath a wraparound skirt that came to just above the knee. For its time the outfit was the most controversial item of women’s sportswear since Suzanne Lenglen had taken to the south London courts a dozen years earlier in a sleeveless top and skirt with no petticoats.

Alvarez’s outfit had been created by the groundbreaking Italian fashion designer Elsa Schiaparelli, who had caused a stir a week before the tournament by wearing a pair of culottes on a shopping trip in London without a covering outer skirt. While the fashion correspondents approved of Schiaparelli’s bold statement, the self-appointed guardians of the nation’s morals did not. Since the Radclyffe Hall trial and banning of her lesbian-themed novel The Well of Loneliness three years earlier, women wearing male-style clothing were always sharply condemned. When Schiaparelli was photographed wearing hers a Daily Mail correspondent was so outraged he declared that any woman wearing any form of trouser “should be soundly beaten”.

Alvarez had worn the culottes two months earlier at a low-key tournament in Highbury, north London, where she told reporters they were not really trousers “rather a divided skirt”, but Wimbledon, a tournament not exactly renowned for its relaxed attitude to progress, was another matter altogether. When Alvarez walked out onto the court wearing a long white cape it prolonged the speculation until she removed her outerwear to reveal the culottes.

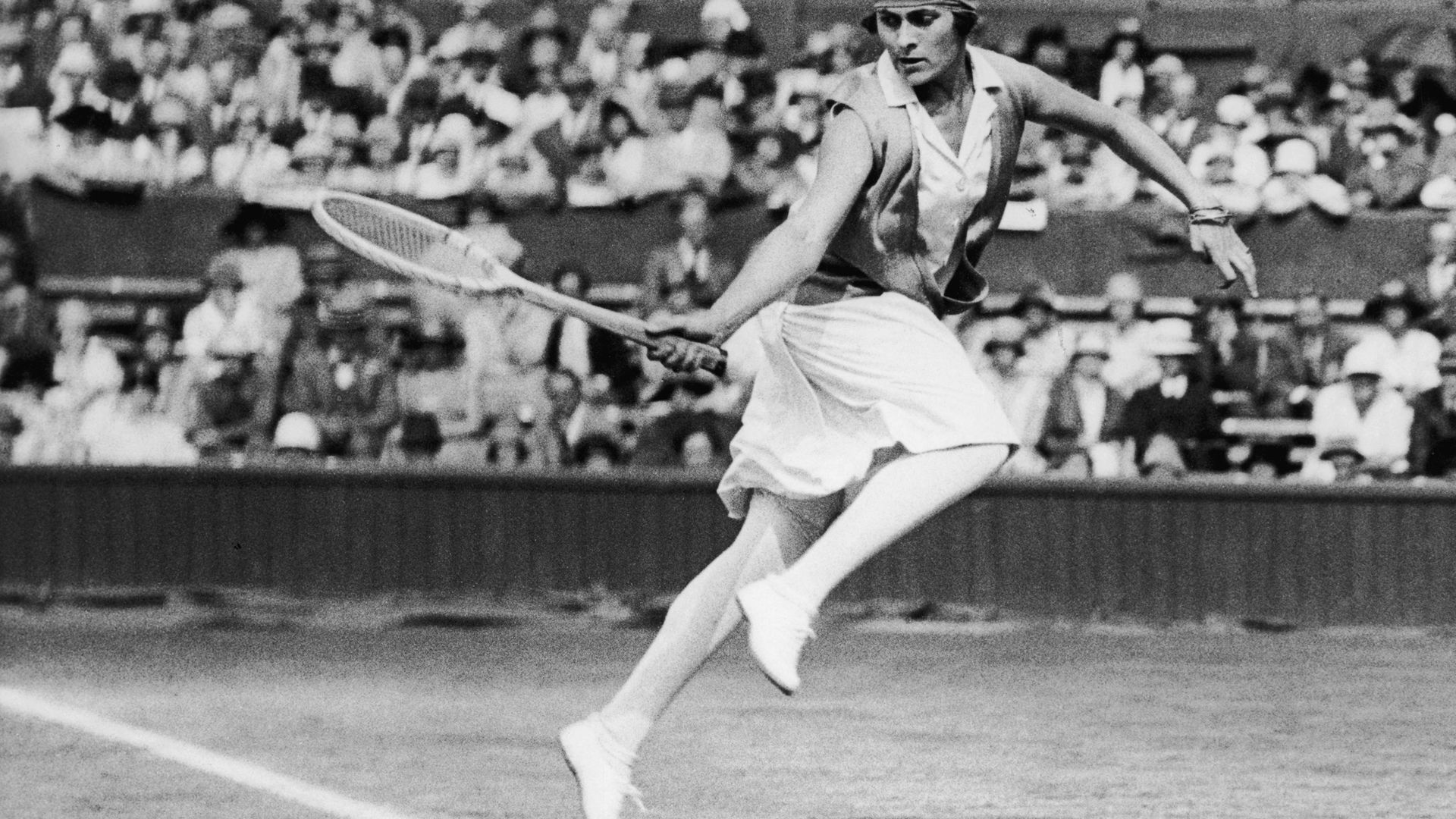

It wasn’t quite as shocking a development as it seemed. For one thing, the trouser legs were so loose-fitting that in ordinary movement and regular play they didn’t look any different from the skirt of her opponent. It was only when Alvarez employed one of her trademark leaps that it became clear there was something more practically suited to sport beneath her skirt than the traditional garb. Comfort aside, her insistence on subverting the male-implemented dress code that day at Wimbledon also spoke of her lifelong commitment to the promotion of equal rights for women.

In fact, if anything Alvarez’s shorts succeeded in deflecting attention from what was arguably the most subversive gesture on the court that day, as Lycett became the first woman to play at Wimbledon bare-legged, without stockings.

After a shaky start – she lost the first set 2-6 – Alvarez stormed back to win the final two sets dropping only three games, before going out in the next round to Dorothy Round in straight sets.

The two matches summed up Alvarez’s tennis career. On her day she was unbeatable, renowned for the precision of her half-volleys and the strength of her backhand. She was unafraid to leave the baseline and liked to play the ball as early as possible. Most of all Alvarez played with a combination of elegance and panache. Even in grainy newsreel footage the languid grace and balance of her movements are obvious.

She was also prepared to go for the big shots, to try something spectacular and adventurous, often to her cost. When those shots didn’t come off, where most players of the day would stare sternly at their racquet strings in the genteel manner of the times Alvarez would throw up her hands and cry, “oh, la la”. When they did come off she would let out a yelp of delight.

Her inconsistency on the court – Alvarez’s only tournament win came in the mixed doubles at the 1929 French Open – was also due to the fact that tennis was not her all-consuming passion. She played to win, but she also played because it was fun.

“I’ve never really been terribly serious about it because there happen to be a great many things in life besides tennis which amuse me,” she said before her first Wimbledon final in 1926. “I get so bored when people meet me and immediately begin to talk tennis. I don’t want to talk tennis. I hate to be regarded as a sort of machine that only begins to function as soon as it is put on a tennis court. I would far rather talk about the theatre, or the ballet, or the weather.”

She was born Elia María González-Alvarez y López-Chicheri, taking her parents by surprise by arriving early while they were staying at a hotel in Rome. She spent many of her formative years in Switzerland, to where her mother decamped due to ill health and it was there she developed her natural affinity physical activities.

As a child she excelled at ice skating, skiing, horse riding and even billiards, which she took up when she was still so young she had to stand on a chair to play her shots. On a visit to Germany in her mid-teens she learned how to tango and immediately won a prestigious competition. As soon as she learned to drive she entered the motor racing championship of Catalonia and won.

In her late teens the family moved to Cannes, where her prowess on the tennis court and effervescent character combined to make Alvarez a popular doubles partner for the rich and famous. She formed a particularly effective partnership with King Gustav V of Sweden, for example, and in 1926, barely two years after taking up the sport in earnest, she’d reached the first of her three consecutive Wimbledon singles finals.

When she married the French count and decorated First World War fighter pilot Jean de Gaillard de la Valdène in 1934, subsequently competing on the tennis circuit as the Comtesse Valdène, Alvarez used their sumptuous Cote d’Azur chateau as the venue for meetings and seminars attended by French feminists, becoming a leading figure in the fight for women’s rights in both France and Spain.

The grief the couple endured after the loss of their first child in 1939 led to the end of the marriage and a move to Spain for Alvarez, where she divided her time between writing on feminist and religious matters and enjoying as much competitive sport as she could.

She had bowed out of the tennis circuit in 1937 after reaching the semi-finals of the French Open and the fourth round at Wimbledon, but she still raced cars and skied to such a high standard she became Spanish champion in 1943 at the age of 38 before immediately falling out with the ski federation when they insisted women competitors be held back until the men had finished.

Her vocal opposition to the changes to the published schedule led to her being accused of ‘insulting Spain’ and the removal of her membership of the organisation. It wasn’t long before the federation sought to make amends with their highest profile woman skier and reigning champion, but Alvarez told them exactly where to go.

It was an episode that summed up her strong sense of social justice and willingness to make the battle for women’s rights personal. She wrote books and countless articles in favour of equality for women, not to mention speaking at congresses, meetings and rallies across the world, but when it came down to it Lili Alvarez was prepared to go toe-to-toe with officialdom and call out ridiculous prejudice wherever she saw it, even if it meant bringing to an end a competitive sporting career that had taken her to the very top.

Age, status, reputation, none of it mattered to her, she was happy to beat the drum for women with the same panache and joie-de-vivre she had displayed from the Centre Court at Wimbledon to the ski slopes of St Moritz to the racetracks of Barcelona. When she met the French marshal Ferdinand Foch, commander of the Allied forces at the end of the First World War, for example, he turned to a companion and said, “I would not dare to propose a game of tennis with that lady”.

“Don’t worry, marshal,” she said in a response as nuanced as it was witty, “I probably wouldn’t declare war on you either.”

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37