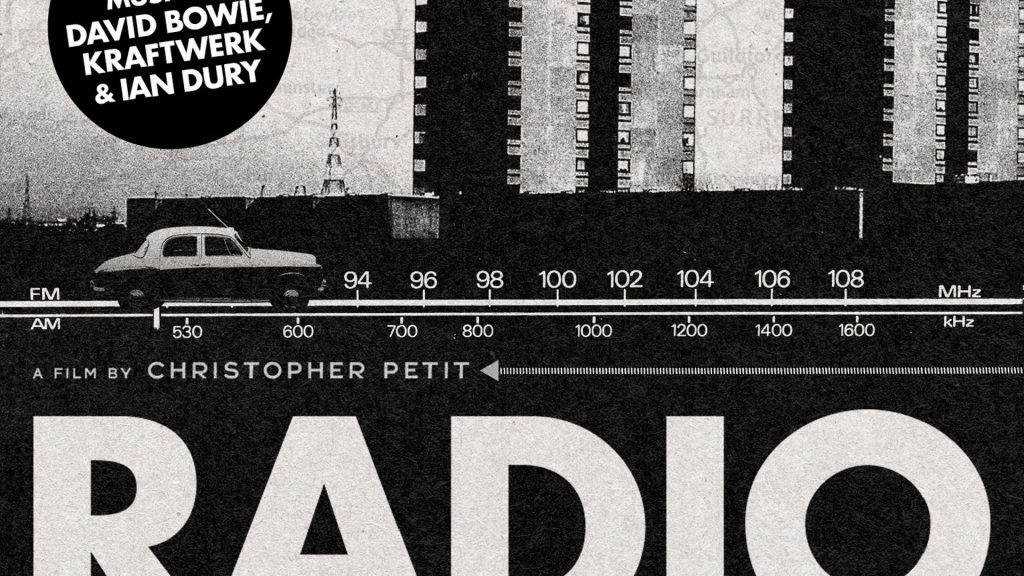

Celebrating a dreamlike cult British take on the American road movie… with German influences

We begin in a flat in London. We end on a train to nowhere somewhere in the south west. In between times, a man half-heartedly investigates his brother’s suicide, listens to some very good music, takes a detour with a nice German lady and has a lovely chat and a singsong with Sting. And all the time late ’70s England looks as if it has one foot behind the Iron Curtain and another in a sci-fi dystopia.

Welcome to Radio On, Christopher Petit’s contribution to that most American of film genres, the road movie. But rather than Route 66, Petit’s interested in the M4 and instead of the fish-eyed lenses and camera flares of Easy Rider, his is a style that openly apes the great European filmmakers of the time. As such, Radio On is the most German-looking movie ever made in the UK by a British director.

That Petit’s picture is often compared with continental classics like Wim Wenders’ The American Friend has more than one cause. Wenders himself is Radio On’s associate producer, his assistant cameraman Martin Schafer serves as Petit’s cinematographer and Weners favourite Lisa Kreuzer is in the role of Ingrid.

Though the Germans weren’t terribly well known in the UK in 1979, they were all hugely familiar to Chris Petit, then Time Out‘s film editor in the days when it wasn’t a free sheet but a comprehensive guide to the world’s greatest city, complete with superb film coverage.

Encountering Wenders while on assignment with the magazine, Petit convinced the great man to back his project – no mean feat given that Petit had yet to make a feature and there’s little in his screenplay that screams commercial success.

The story, such as it is, centres around Londoner Robert (jobbing actor David Beames) who earns a crust spinning the discs on the United Biscuits radio network. Upon learning that his Bristol-based brother has taken his own life, Robert – after much dithering – heads west to find out what caused his sibling to take such drastic action.

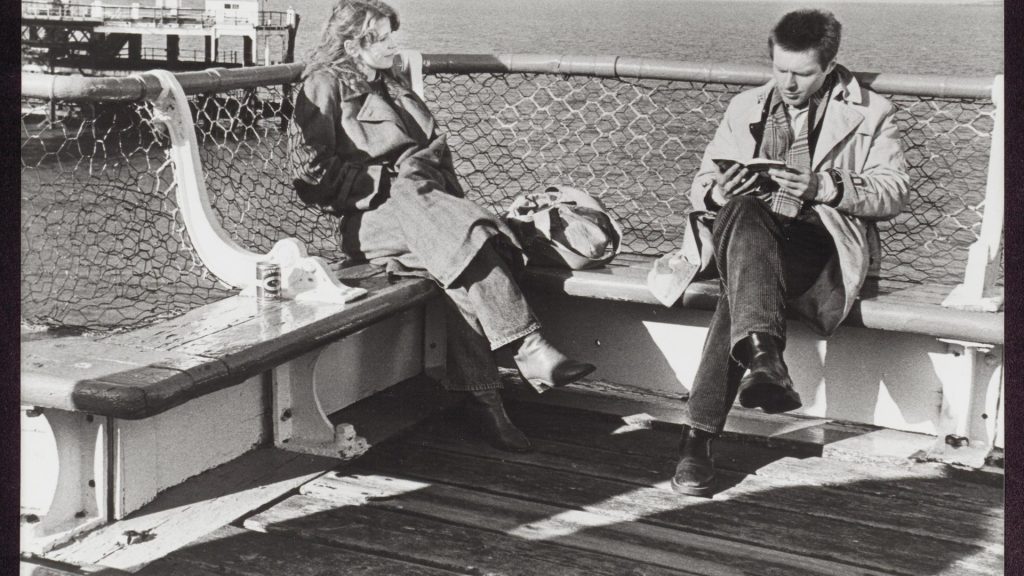

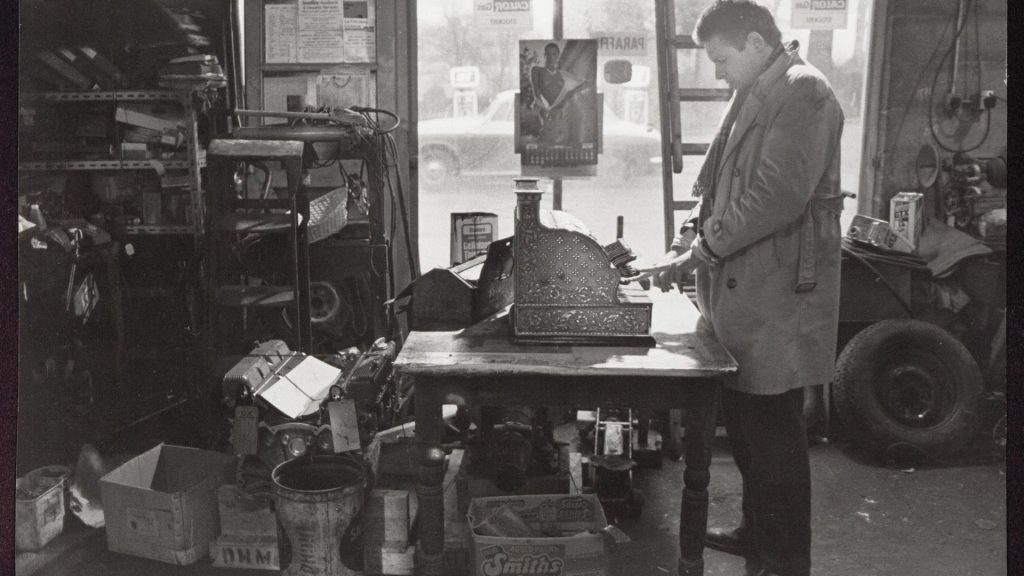

During the journey, he encounters a variety of outsiders – an army deserter, an Eddie Cochran-obsessed petrol pump attendant, a German woman who has lost custody of her child – each of whom seems to occupy him far more than getting to the bottom of his brother’s death. Eventually abandoning both his investigation and his vintage Rover, Robert boards a train and heads off into an uncertain future.

It’s very much to Petit’s credit that he’s never tried to disguise Radio On’s obtuseness. Upon presenting the movie at a festival the year after its release, the writer-director explained that while his “is a film in black and white, it’s not Manhattan. I’m also told that it’s a film that divides its audience so I hope that at least a few of you are left [for the Q&A] at the end.”

Of course, were it a more traditional film, it’s unlikely we’d be talking about Radio On with such reverence today. Likewise, were it not for the film’s otherness, it mightn’t have been such a hit with the midnight movie crowd at the Scala and the Screen On The Green.

With its impressively blank lead and its austere black-and-white cinematography, Radio On insists on so little that the viewer is free to interpret the events it depicts in pretty much any manner they choose. For this writer, it’s that rare picture that travels backwards and forwards in time without resorting to either flashbacks or special effects. Take the petrol station that Sting attends to – it looks for all the world like the one Roald Dahl describes in the ’50s-set Danny, The Champion Of The World.

The Westway, on the other hand, has seldom looked more like a runway for a vehicle that’s still to be invented. And as our hero settles down for the night at Bristol’s Grosvenor Hotel, the nearby flyover gives the impression that the cars are actually flying past his third-floor window.

But while moments such as Robert having to use a hand-crank to start his car recall a very different age, certain incidents in Radio On tie it firmly to the late ’70s. Take the Scottish squaddie who has clearly left more than just his regiment in Northern Ireland. And then there’s the soundtrack with its trio of Kraftwerk tracks, its brace of Bowie numbers and contemporary hits courtesy of Lena Lovich and Ian Dury.

Even here, though, all is not as it might sound. Giving his soundtrack the sort of billing usually reserved for a film’s cast, Petit yet again whips back and forth through time. Whether it’s Devo covering the Stones’ Satisfaction or Dury memorialising Gene Vincent, today and yesterday once more appear on an even footing; a state of play that reaches its peak when Robert and Sting’s pump-boy perform a charming acoustic rendition of Eddie Cochran’s Three Steps To Heaven.

Mr Sumner is very good, too. No matter how badly he’s stunk up the screen in pretty much everything else, he’s positively delightful here – a rare blast of warmth in a wintery world dominated by concrete eyesores and slate-grey skies.

As for the journey proper, its conclusion, complete with Robert driving around a quarry in circles, brings to mind the penultimate image in another classic German art film, Werner Herzog’s Strozek. That was the film Ian Curtis watched before he hanged himself.

Is it a coincidence that Robert, what with his sharp haircut and gabardine raincoat, looks rather like the late Joy Division singer? Probably, but with Radio On, nothing is for certain.

Speaking of uncertainty, one wonders where Chris Petit thought Radio On might take him next. The answer was An Unsuitable Job For A Woman, a PD James adaptation recently available on All 4. Since then he’s produced a diverse body of work including a Robbie Coltrane thriller Chinese Boxes, a BBC Miss Marple mystery; 2002’s London Orbital, a pseudo-documentary about the M25 and several acclaimed novels, the most recent being The Butchers Of Berlin, a police procedural but with cops replaced by the SS.

Yet it’s Radio On people return to. Whether it’s the graffiti calling for justice for Baader-Meinhofette Astrid Prol or the sight of a Rover on a cliff-edge, its doors wide open all the better to allow the world to enjoy Kraftwerk’s Ohm Sweet Ohm, there are sounds and images here that live on in the subconscious mind like the most vivid of dreams, the most troubling of nightmares.

And while dislocation is among the themes running through Petit’s film, there’s a generation of people for whom a few bars of the German version of Heroes or the insistent pulse of Kraftwerk’s Radioactivity are all they need to find themselves returned to the Westway.

Radio On is out now on BFI BluRay

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37