CHARLIE CONNELLY on a truly epic novel which pays fitting tribute to the female pioneers of aviation

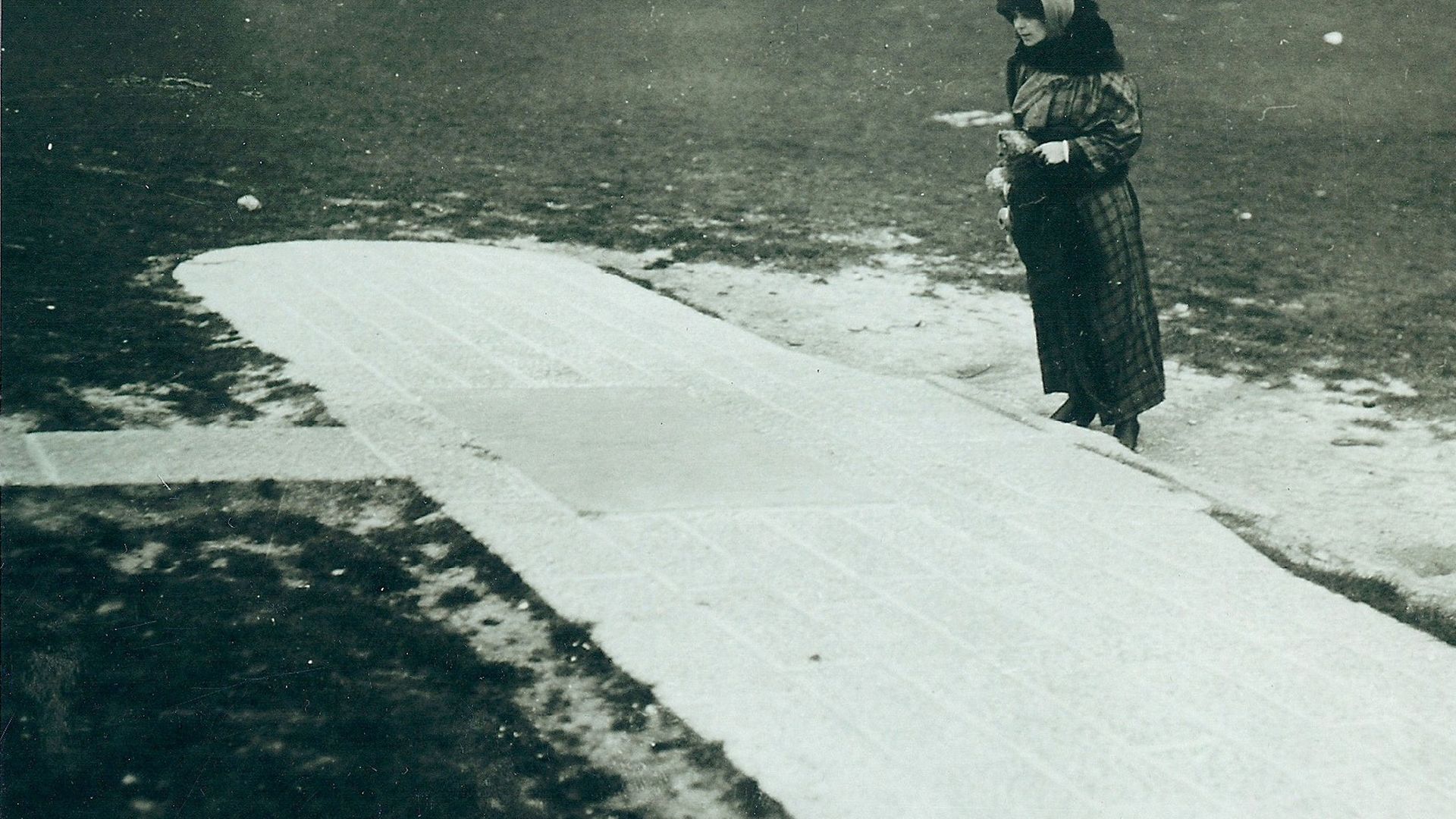

One of my favourite historic photographs was taken 99 years ago. It’s of a young woman, wrapped up in a heavy coat and headscarf against a cold wind coming in off the sea, standing alone in a field outside Dover in front of the concrete outline of an aircraft set into the grass.

It’s a monument marking the spot where Louis Bleriot landed in the summer of 1909 to complete the first powered flight across the English Channel and the woman is reading the plaque set between the concrete wings. Her mouth is open slightly and there’s a hint of a smile; despite her buttoned boots you can tell she’s on the balls of her feet and even though she’s swaddled in clothing her body is tensed with anticipation, as if ready to spring. She looks almost as if she’s about to take flight herself.

Her name is Harriet Quimby, the photograph is from April 15, 1912, and the following day she will become the first woman pilot to cross the English Channel.

Michigan-born, San Francisco-raised, Quimby came from a poor background yet forged a multi-faceted career for herself as a model, journalist and the writer of seven Hollywood screenplays filmed by legendary director D.W. Griffith. Most significantly, she was America’s first woman pilot. She’d learned fast, too: on the day that photograph was taken it was still not even a year since she’d sat in an aircraft for the first time.

It’s often overlooked that women were a major part of aviation from the start. Amelia Earhart and Amy Johnson remain the two most famous female pilots from the early days but from the 1920s in particular in Britain, the US and France women pilots were almost commonplace. Most came from wealthy families, women who would never be poor but who would never inherit and never have a career. A dull husband, a scatter of children and hosting the odd ball were about the limit of expectations for generations of intelligent, gifted, adventurous young women.

Flying gave them freedom and independence. In the air, at the controls, the artificial restrictions of their class and gender became meaningless. Even age didn’t matter: Mary Russell, the Duchess of Bedford, learned to fly in 1928 at the age of 63. That year Mary, Lady Heath, became the first pilot, man or woman, to fly from Cape Town to London and Sicele O’Brien from Dublin set up the first air taxi service.

Flying was new, exciting and, for the wealthy, accessible. It was also dangerous. The Duchess of Bedford, having ranged as far as India, Nigeria and South Africa, disappeared over the North Sea in 1937. Sicele O’Brien, having lost a leg in a 1929 crash, was killed in 1931 in an accident at Hatfield Aerodrome. What makes the photograph of Harriet Quimby at Dover even more poignant is that this woman captured practically fizzing with life and potential has barely three months to live, killed when her plane’s nose dipped suddenly, causing herself and her passenger to fall out of the cockpit into the sea off Squantum, Massachusetts. Amy Johnson and Amelia Earhart would both also die before their time while wearing flying suits.

There were exceptions, like Mildred Petre, who went by her married name of Mrs Victor Bruce. Having already driven a car 250 miles north of the Arctic Circle, further north than anyone before, in September 1930, eight weeks – eight weeks – after she’d sat at the controls of a plane for the first time, she set out from Heston Aerodrome to fly solo around the world.

Four days later she crash-landed on a salt flat in the searing heat of the Persian Gulf before being rescued by local tribesmen, flew on to Calcutta, Rangoon, Bangkok, Hanoi, Seoul and Tokyo where she was caught up in an earthquake. She put her plane onto a liner to Vancouver (it would be another five years before Amelia Earhart became the first solo pilot to cross the Pacific), flew down the west coast of America to San Diego then turned east, hopping across the US to New York. She sailed the Atlantic to Le Havre before flying the last leg to Croydon aerodrome escorted the whole way by Amy Johnson herself. Unusually for an early aviator Mrs Bruce lived to a ripe old age, celebrating her 78th birthday by test-driving a Ford Capri Ghia at 110mph around the track at Thruxton.

In 2012 the American author Maggie Shipstead emerged from Auckland airport and saw the bronze statue there of Jean Batten, the New Zealand aviator who made several record setting long distance flights during the 1930s, covering huge parts of the globe. The statue shows Batten with a bunch of flowers clamped by her left arm while she waves with her right, above the inscription “I was destined to be a wanderer”. The statue and the phrase stayed with Shipstead and now, nine years on, comes her vast, epic, global sweep of a novel Great Circle, the story of an American pilot named Marian Graves who goes missing near New Zealand in 1950 on her way to completing a circumnavigation of the globe via both poles.

Two years after Shipstead stood in front of Batten’s statue she commenced work on the novel that would become Great Circle. No wonder it’s taken seven years to appear; rarely have I picked up a novel of such scope and scale. Not only does its geography cover much of the globe, from Alaska to Antarctica, from minor Aleutian islands to Hawaii, Hampshire to Sweden, the great circle of the title also encompasses the birth-to-death stories of a range of characters so vividly realised that even when a character dies just a few pages into the book the reader feels a wistful pang.

In a parallel narrative Hadley Baxter, a former child star made globally famous by a Twilight-style film franchise, has fallen foul of tabloid scandal-mongers and is rebuilding her career by playing Marian in a biopic, making Great Circle the twin story of women kicking against the patriarchy.

Great Circle is a huge gear shift for Shipstead. In 2012 she published her debut Seating Arrangements, a romantic comedy about a family wedding in New England. Two years later came Astonish Me, a sharply observed novel about the world of ballet. Well-received as they were, they were miniatures compared to the vast canvas of this extraordinary novel.

For a book stretching to almost 600 pages there is not a spare word, nor a scene that isn’t vital in moving the plot forward. As a feat of imagination alone the novel is a huge achievement, turning it into such a compelling narrative will make even other established novelists want to pack it in.

“I wish to measure my life against the dimensions of the planet,” says Marian, echoing the ambition of this work by its author. Flying made the world smaller, Great Circle seeks to re-establish its vastness.

Marian and her twin brother Jamie are lucky to make it out of their swaddling clothes. The transatlantic liner captained by their father sinks during the First World War. Addison Graves, overseeing the rescue attempt, suddenly jumps into a lifeboat with his babies, an act for which he is later vilified as a coward and spends years in prison. But the children survive, being sent to live with a kindly but flawed artist uncle in Missoula, Montana. They grow up in the landscape, allowed to range far and wide, until one day 12-year-old Marian is accidentally buzzed by a biplane belonging to a travelling show of barnstormers arriving in Missoula. At that moment is born an ambition that will define her life, one forged “at an age when the future adult rattles the child’s bones like the bars of a cage”.

She’s spent her childhood reading books from her father’s library (Addison, released from prison, spends one night in Missoula before vanishing), epic travel narratives from the Lewis and Clark expedition to the voyage of the Beagle, tales from a wider world that always seemed a long way from Montana. Until, that is, the miracle of flight enters her life.

We follow Marian as she drives a truck for a bootlegger to raise money for flying lessons, becomes entangled in a toxic relationship, decamps to Alaska and a job involving some of the most challenging flying in the northern hemisphere, crosses the Atlantic to serve as an Air Transport Auxiliary pilot in the Second World War, delivering and transferring aircraft between bases in Britain, and then embarking on the epic flight that defines her life and gives the book its title.

Hadley Baxter meanwhile is enduring the fallout from one night of letting herself go, being photographed with a notorious womaniser in a way that brings her close to ruining her career (while the man involved suffers no backlash, of course). There’s practically a whole novel within the novel in Hadley’s story, a wise analysis on the nature of celebrity especially when it’s bestowed upon a young woman. But when she accepts the role of Marian in a small, independent production much reduced from the familiar major studio whirl she becomes ever more drawn to Marian, immersing herself in her story even if she isn’t entirely sure why.

Great Circle is layered with themes and narratives and individual stories woven together in a way that ensures the pace never dips while the reader never loses track of a wide-ranging story. There is no need for a Wolf Hall-style glossary of characters here. In fact, comparisons with Mantel’s trilogy are not misplaced: Great Circle has much to say on how we tell life stories. As Hadley learns more about Marian’s story she realises how much of the accepted narrative has been twisted, mainly through a presumptuous sensationalised biography that’s being adapted loosely for the screen. We experience this alongside Marian’s ‘real’ narrative and see the liberties taken and errors made, prompting questions about who really owns our stories.

“I’ve had stuff about myself, information, get launched into the world – or I’ve done the launching – and I’m not sure what difference it makes how much strangers know about you,” says Hadley. “They still don’t know anything.”

The names of Amy Johnson and Amelia Earhart will be the ones that come to mind when reading Great Circle, yet I thought immediately of Mildred Petre, aka Mrs Victor Bruce, who in her first time in a cockpit had a vision of the world and its possibilities and took off to explore them just two months later.

I also thought of that picture of Harriet Quimby, an image brimming with possibility and potential, of achievements yet to come, and the other fearless women who took to the air, those destined to die in their dotage, those destined to meet their end in the wreckage of the machine that lifted them from convention into a realm of exhilarating achievement. Great Circle is a fitting tribute to them all.

Great Circle, by Maggie Shipstead is published by Doubleday, price £16.99

FIVE GREAT BOOKS OUT THIS WEEK

AN EXTRA PAIR OF HANDS: A STORY OF CARING, AGING AND EVERYDAY ACTS OF LOVE

Kate Mosse (Wellcome Collection, £12.99)

If the last year or so has taught us anything it’s the importance of carers to the well-being of the nation. In this memoir bestselling novelist Mosse meditates on time spent helping her father through Parkinson’s, her mother through her subsequent grief and then helping care for her nonagenarian mother-in-law. Sensitive and compelling.

SANKOFA

Chibundu Onuzo (Virago, £16.99)

Anna grew up in England with her white mother, knowing little about her West African father. In middle age she learns of his involvement first in radical politics in 1970s London and then how he went on to be president – some would say the dictator – of the West African state of Bamana. A funny, gripping novel of identity and belonging.

AN EXPERIMENT IN LEISURE

Anna Glendenning (Chatto & Windus, £14.99)

Grace, a Cambridge graduate from West Yorkshire, arrives in north London in 2015 ready to take on the capital in all its craft beer and gluten-free glory. Soon she finds the city to be loneliest place in the world, prompting a journey of self-discovery that takes her up and down an increasingly divided country in search of her place in the world. A wise novel with plenty of heart.

THE SUITCASE: SIX ATTEMPTS TO CROSS A BORDER

Francis Stonor Saunders (Jonathan Cape, £18.99)

Ten years ago Francis Stonor Saunders was given a suitcase of her late father’s papers with a warning that if she opened it she’d never close it again. In it she finds a tumultuous story of Europe and an insight into the father who in life had been an enigma to her. An absorbing journey into the nature of biography, history and the stories of ourselves.

CWEN

Alice Albinia (Serpent’s Tail, £14.99)

Set on a fictional archipelago to the east of Britain, Albinia creates a ‘gynotopia’ in which women are in charge. Of their bodies, of their politics, of their families, of their careers. When the founder goes missing we meet the mysterious and ancient spirit Cwen, guardian of the islands and their women in a thrillingly original tale of female empowerment.

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37