A new exhibition at Amsterdam’s Rijksmuseum examines the tools of the cruel slavery trade

It looks like a dog collar, albeit a rather fine one, in richly decorated brass and engraved with acanthus leaves. Dated 1689, it is embossed with the names of its owners, Maurits, Count of Nassau La Lecq and his wife.

When it was donated to Amsterdam’s Rijksmuseum in 1881 it was described as a dog collar but it is unlikely that such an elegant ornament was used for controlling wayward canines. More likely it encircled the neck of a servant, a black servant, for while slavery had been banned in The Netherlands since the Middle Ages, owning a human, particularly a young boy, to help around the household and to serve as a plaything or a form of entertainment was perfectly acceptable. The shiny collar was proof of ownership.

Slavery, at the Rijksmuseum until August 29, unflinchingly confronts how the slave trade, which was finally banned in 1863, is inextricably bound up with the years of Dutch colonial rule which reached its apogee from the 17th to the early 19th century and stretched across the globe from the Dutch East Indies, to Africa, and the Caribbean.

The exhibition tells the stories of ten real people drawn from administrative documents, judicial records, even a journal kept on a slave ship, as well as oral testimony handed down over the years. As well as a guided virtual tour of the galleries, often by someone who claims a slave as an ancestor, a striking array of artefacts and paintings illustrate not just the terrible fate of the slaves but the cynicism and cruelty of their owners.

Their stories, record all too familiar tales of greed, exploitation, and outright savagery, all predicated on the horrible assumption that one human could be the property of another and as such had no recourse to justice. The slave owner could do as he willed with his possession. There was no retribution for abuse, cruelty or rape – after all, how could ‘property’ suffer?

As the introduction to the exhibition states, the fate of the property was to be “tallied in the records along with tools and livestock.”

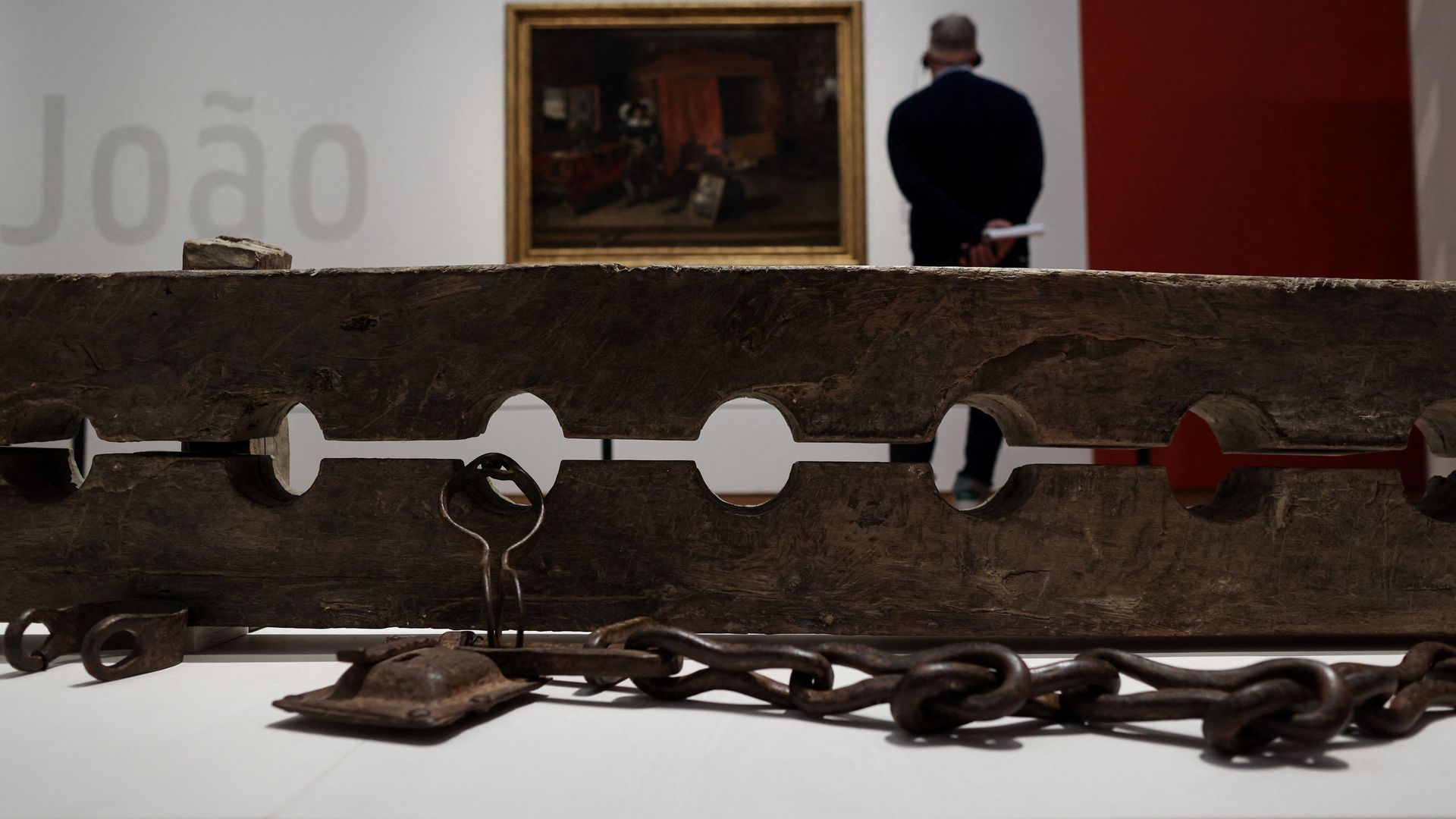

Anyone who attempted to break the chains of servitude was punished with primaeval cruelty, such as the slicing off of a breast or tearing away flesh with red-hot pincers before burning victims alive, decapitating them and displaying their heads on spikes as an example to others. Branding and whipping were routine, as well as being locked by the ankles and forced side by side into a foot stock known as a tronco, two timber sections connected by an iron hinge at one end and an iron lock at the other.

So, the innocent dog collar takes on a painful resonance. We have the name of one servant, Paulus Maurus, who served in the Maurits’ household and was one of the lucky ones. His owners flaunted their wealth by having him in their service, they educated him, had him baptised and converted to Christianity. He was even allowed to marry.

In one painting we see him gazing in awe and trepidation at his master who is seated proudly on his prancing horse while young Paulus has his helmet ready for action. And, again, here he is playing the drums at the head of the military cavalcade. It looks grand, it looks liberated, but he is still wearing his collar.

Most property did not fare as well. Far from the opulence of Dutch high society, in January, 1662, ten boats headed for the Bengali city of Pipeli.

A Dutch surgeon, one Wouter Schouten, describes how the small vessels were packed with “unfortunates” lying on their backs, bound with nooses around their necks and arms, and barely able to move.

“Anyone can imagine what a miserable groaning, weeping and heartbreaking whimpering these unfortunates utter,” he wrote. “Forlorn people who only days before lived in comfort and freedom, were now robbed of everything, tied up and beaten, taken, poor and naked, into slavery.”

These were van Bengalen, the surname given to all inhabitants of the Bengal region owned by the Dutch, and they were to be deported to Batavia (present-day Jakarta, Indonesia) and to work on nutmeg plantations on the Banda Islands in the Moluccas (Maluku Islands), where some 14,000 of about 15,000 inhabitants had been massacred the year before.

Between 1624 and 1665, the Dutch bought and transported 26,885 people to Batavia and more to the Cape in South Africa. Thanks to the records of the days we have examples of their sufferings. To take only two from the thousands who tried to escape or lost the will to struggle against their bondage; on February 1, 1729, Amon van Bengalen hanged himself from a tree in the garden of the house where he worked in Batavia. The surgeon who examined the body also listed many other enslaved men and women who had hanged themselves or slit their own throats.

Susanna van Bengalen was also known as Een Oor (‘one ear’) because of her mutilated ears – a punishment for an unspecified crime. She was banished to Cape Town, where she was placed in the “slave lodgings” and worked in the gardens. Suffering from the pox and struggling to cope with a sick child, it would seem she had a breakdown and strangled the child with three strips of cloth. Susanna denied the crime but after being tortured with thumbscrews, she confessed. The sentence read: “The murderess, upon having her breasts torn from her body with red-hot pliers, shall be burnt to ashes here outside the fort.”

In the event, it was considered more merciful to cast her in a sack into Table Bay and let her die from drowning. The residents of the slave lodgings who had reported the strangling were forced to look on as she sank beneath the waves.

Her fate has been preserved in gruesome detail but she was not alone. Thousands – millions – were taken from their homes, whipped, branded and dragooned into forced labour like a young man called Wally who worked on a sugar plantation on another part of the Dutch empire, Surinam. After many altercations with his owners, he was arrested in 1707 for protesting against the banning of the slaves’ annual celebration, a joyously defiant affair judging by a painting of the fiesta.

He and his rebellious companions went into hiding before handing themselves to face their punishment which would have been “death in the most painful and most protracted way possible” with immolation and decapitation as part of their fate until the local governor retracted, fearful of more unrest in reaction to the carrying out of the sentence.

We get a glimpse into the intractable attitude of the owners in Wally’s own words when he was being interrogated about his protest: “[He] Says that the manager, Christiaan, on the arrival of the ships carrying the governor, read them out all a letter from Mr Witsen, in which it was ordered that no negro was to leave the plantation without a pass.”

Witsen, the plantation owner, instructed that the slaves had to work harder to maximise the profits and insisted on instilling fear into the workers, who outnumbered their masters, with daily punishments. Their tasks were unrelenting. The slaves had to reclaim the land, build canals and trenches for drainage and transport, burn the fields to clear them of weeds and vermin and replant the entire sugar crop every three or four years. All that, before the task of reducing the sugar cane juice in the boiling house which was a hazardous job and one which often ended in burnt limbs.

Such was Mr Witsen’s callous disregard for his property that he never visited the source of his immoral earnings, preferring to stay in considerable comfort in his home in Amsterdam and survey his domain by admiring a series of elegantly drafted drawings paintings he had commissioned from a popular artist of the day.

But as Wally’s protests and fights with the overseers suggest, the slaves often showed a heroic refusal to be cowed by their subjugation and to escape whenever they could.

A female slave on the island of Sint Maarten in the Caribbean was known as One-Tété Lohkay, or ‘Lohkay with one breast’ because she had been mutilated after an escape attempt in 1848. Undaunted, she fled again to the island’s hilly interior where her defiance inspired many of her fellows to join her in a series of mass escapes.

Such was her influence that before slavery had been officially abolished in 1863 plantation owners had no choice but to accept the de facto freedom of all the islands’ inhabitants. Her story has been passed down by oral traditions but a deceptively pretty watercolour of the plantations and the hills where she hid contrasts with the harsh reality expressed on a china plate inscribed with the words “Bring more cane to the mill negro”.

In the story of Ma Sipali, there is an intriguing insight into the way the slaves of Surinam survived in secret communities, hidden from their oppressors. Known as Maroons, (from the 17th century Spanish cimarrón, wild or runaway slave) they learned one ingenious method of survival was to smuggle rice seeds in the braids of their hair. A rather moving reconstruction shows how one woman would arrange the hair of another with a crude wooden comb so that rice grains could be sprinkled in the parting. The hair is divided into three and braided. As the braid pattern grows, the grains vanish from sight, well hidden within the hair.

All the testimony of the slaves, their owners and observers are accompanied by fine and fascinating imagery but one of the ironies is that many are drawn from the collection of the Rijksmuseum itself and other Dutch museums and are often about the wealthy elite and, indeed, intended to be in recognition of their status.

The result is that many of the paintings hide a shameful past. Take, for example, the portraits of Oopjen Coppit and her husband Marten Soolmans, a wealthy young couple whose portrait was painted by Rembrandt, no less, in 1634. So important was the work deemed to be when it was acquired for the museum in 2017 that it was hung alongside the painter’s masterpiece The Night Watch in the museum’s Gallery of Honour.

But, once the curators began the planning for the Slavery exhibition they examined the lives of the couple. It transpired that they, like so many others of the Dutch richer classes, owed their wealth to the sugar trade which relied entirely on slave labour for its success. Would Oopjen have known where her husband’s money came from? Would she have cared?

Oopjen remarried to one Maerten Daey, who owned a sugar plantation in Brazil. We get a sense of his lifestyle from paintings of the day but we have only the briefest details of the young native girl he held captive for four months, raped and impregnated. Her name was Francisca, her baby’s Elunam. She disappears from the story, a victim of casual depravity. A half-hearted attempt by the local mayor and pastor to indict the assailant came to nothing and Daey was free to continue his life untroubled by any fear of retribution.

The museum is all too aware of these awkward truths. In the exhibition catalogue, the head curator writes: “What we can do, however, is point out to the visitor what may not be apparent, or is not shown, in a painting of a plantation; the awkward contrast between idyllic representation and harsh reality; and the stereotyped depictions of, and lack of real faces given to, enslaved people”.

Slavery is at the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, until August 29.

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37