How the friendship of tragic poets Sylvia Plath and Anne Sexton, forged over long, cocktail-soaked lunches, paved the way for the rest of us

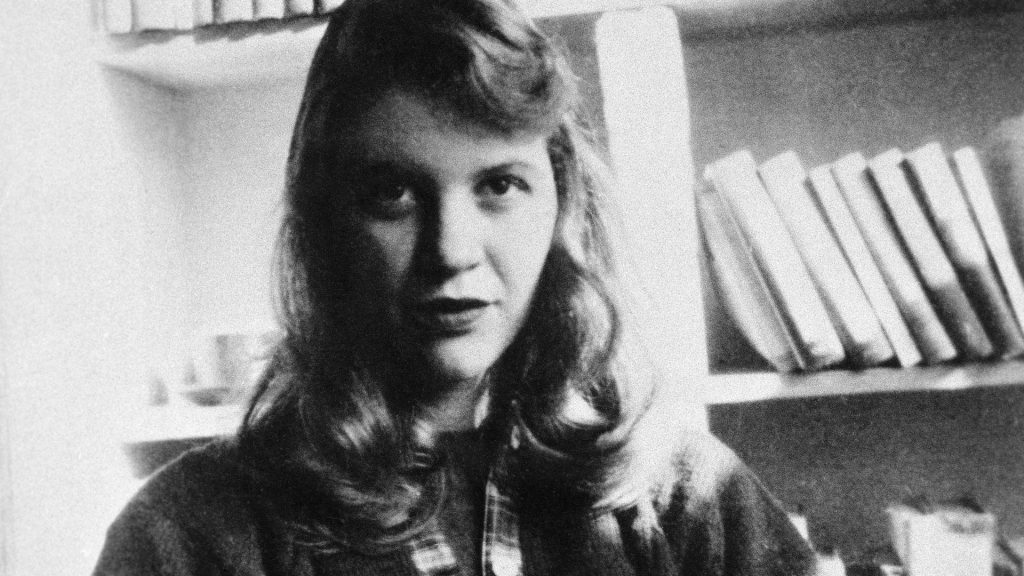

In 1950s America, white, middle-class women were not supposed to be ambitious. In fact, women were respected for not pursuing their own careers and instead focusing their attentions on the home and family. Sylvia Plath and Anne Sexton were born into this cultural moment and reached their formative years when this ideology of the dutiful woman was at its height. When Plath graduated from Smith College, her commencement speaker, Adlai Stevenson, praised the female graduates and pronounced that the purpose of their education was to help them become intelligent, interesting wives.

But in 1959, Sylvia Plath and Anne Sexton met for the first time at a poetry workshop run by Robert Lowell at Boston University. They were both aware of the challenges facing them as aspiring writers trying to get ahead and be successful in a male-dominated literary discipline. For this short period of time, a matter of months, the two women’s lives collided.

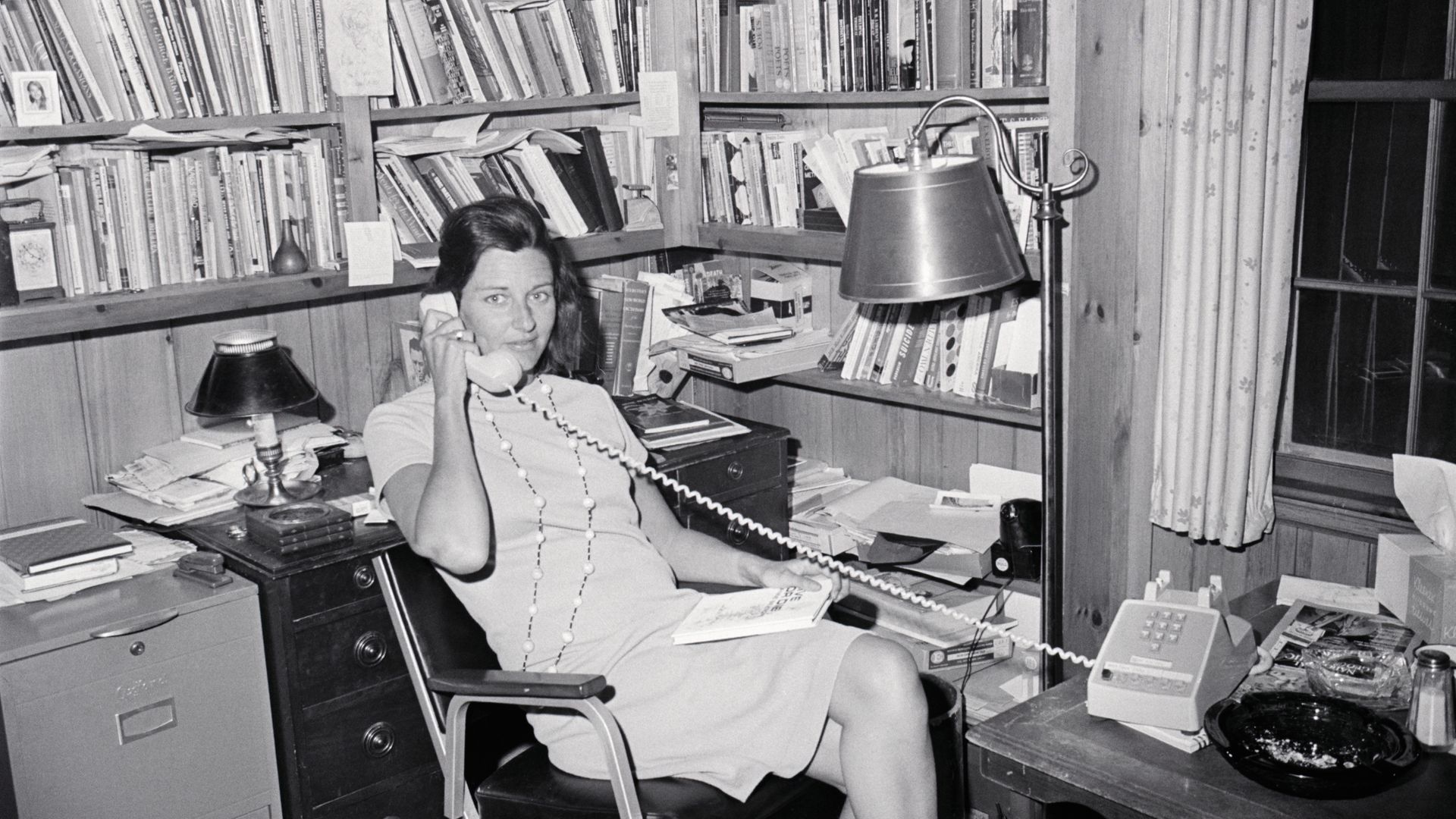

They were very different in style and personality. Plath would arrive early to class wearing a sensible blouse and cardigan, sitting poised and ready with her notepad and pencil. Sexton would often be late, bursting into the room in a dramatic fashion, all brightly printed dresses and jangling jewellery. She used her shoe as an ashtray.

Both in their own way created an atmosphere of awe among other students. After a couple of sessions, Lowell made Plath and Sexton team up and work together. “An honor, I suppose,” wrote Plath begrudgingly in her journal.

But a friendship soon developed from their initial suspicious circling of each other. On a Tuesday after class Sexton would drive them to The Ritz-Carlton in her old Ford to drink three martinis and talk intensely about life, poetry, suicide, and death. Pulling up in a Loading Only zone, Sexton would yell “It’s okay, because we are only going to get loaded!”

Then, over dishes of free potato chips in the hushed, red hotel bar they would pile their books and papers on the table, and talk. Both understood the tensions and challenges of trying to negotiate their way through the world balancing their desire to be wives, mothers, and writers. Both had a strong sense of social rebellion and a belief that women were more than entitled to their own careers.

Now, years later, the poets are long gone from The Ritz, and the martinis consumed. But the aftermath of those conversations ripple uneasily through time and space. This is partly because both poets trouble what society and culture does to women.

Their voices disrupt dominant ideals as their poems tear apart unfaithful men, gender expectations, the difficulties of marriage, how it feels to be a mother, a woman, a woman who menstruates, suffers miscarriages, who enjoys masturbation, and sex. On those springtime Boston afternoons during their confessional drinking, Plath and Sexton were more radical than they realised. They began to pave the way for the rest of us.

Sexton lamented that often it felt as thought she was kicking at the door of fame which men owned and would not share the password for. My new book, Three-Martini Afternoons at the Ritz: The Rebellion of Sylvia Plath and Anne Sexton examines all the ways in which these two women extraordinary women just kicked the door down anyway and found fame on their own terms as their lives became a juggling act between the personal, domestic, and professional.

There are two items in the Plath and Sexton archives that evoke a sense of social rebellion. Their address books.

Plath’s is a green snakeskin-patterned pocket-sized book filled mostly with her immaculate handwriting, notes, and annotations. The front cover has the word Addresses on it in embossed gold lettering. The black ink is shiny in places, almost wet looking.

Sexton’s is a loose-leafed vibrant red folder that still retains an odd odor. When the archive storage box is opened, it exudes a faint smell of musty nicotine. The plastic cover is sticky to the touch. The front page has a vague imprint of the word Telephone engraved around the bottom of a square plinth holding a picture of what looks to be a once-gold telephone. This item was left on the top of Sexton’s filing cabinet by her desk at the time of her death.

Like Plath, Sexton’s address book was important to her, so important that she wrote a poem about it called “Telephone,” beginning with a clear, accurate description: “Take a red book called TELEPHONE, / Size eight by four. There it sits. / My red book, name, address and number. / These are all people that I somehow own.”5

While the poem then muses upon all the “dear dead names” that “won’t erase” from the book, what we can see in Sexton’s list of contacts is how closely family, therapists, psychiatric hospitals, suicide hotlines, and pharmacies sit side by side with journals, editors, poetry prize committees, and university contacts.

As with Plath’s address book, Sexton’s showed the range of people she was dealing with and the almost double life of housewife-poet, or, as she put it, “I do not live a poet’s life. I look and act like a housewife” until the point when a poem has to be written and then, she writes, “I am a lousy cook, a lousy wife, a lousy mother, because I am too busy wrestling with the poem to remember that I am a normal (?) American housewife.”

The tension of these two areas running alongside each other, the housewife-mother and the professional poet, was one that both women felt throughout their careers. But it was a position that was frowned upon at the time.

Women were expected to sacrifice their careers to ensure a stable home. In fact, in more affluent homes, if women chose to work when the paycheque was not needed, they were regarded as selfish for putting their own needs before those of the family. Marriage and children were part of the national agenda and regarded as one feature that made America superior.

Operating within the Cold War agenda, stay-at-home mothers were contrasted favourably with mothers in communist Russia who worked in dismal factories and left their children in cold day-care centres. American wives could be well-groomed, focusing on orderly homes and tending to all their children’s needs. As a result of this propaganda, by the 1950s marriage rates were at an all-time high, and women were getting married younger.

Despite the power of this message, neither Plath nor Sexton could fully accept this cultural norm. And yet neither could, at first, fully reject it either. What Plath and Sexton did try to achieve was a subversive rebellion that increasingly became an open rebellion as they found their voices and their platforms from which to speak.

If in 1950s America women of a certain class were supposed to sacrifice their own careers for those of their husbands, Plath and Sexton were having none of it. Both became increasingly outspoken in their poetry, prose, interviews, and correspondence while somehow balancing this against staying fairly conventional in their home lives.

What they did establish was a position that would last for the rest of their lives and afterlives—that of women who refuse to be silent. Their voices were not just asserting some louder version of the oppressed female experience; their voices were confrontational and started to open up a space for women to express anger, disgust, frustration, and dissatisfaction. Rage became legitimiSed.

They also began writing about the female body in a way that caused genuine shock and revulsion among male editors and critics. Plath’s poems, such as “Lady Lazarus,” “Daddy,” “The Applicant,” and “Fever 103°,” were regarded as dangerously extreme. Sexton’s poems, such as “The Abortion,” “Menstruation at Forty,” and “The Ballad of the Lonely Masturbator,” sent some male critics into apoplectic rage—rage and criticism that Sexton then took on and replied back to in her poems, which presumably left the critics even more paralyzed with fury.

The result was that Plath and Sexton were, and still are, regarded as both troubling and troublesome figures in society. Their work is subjected to the kind of misogynistic critique rarely heaped on other writers.

Although both died young, Plath and Sexton have never really gone away. This presence is around in a number of ways. Their personal possessions in archives re-create an evocative sense of being; address books, dresses, calendars, diaries. Their books remain in print, and their poems anthologized.

In the 1950s just as Plath and Sexton were beginning to find their voices, they could not have known how rebellious they would end up being. They could not know they were about to become two of the most prominent voices in 20th century poetry, disrupting and troubling the social landscape decades after their deaths.

What do you think? Have your say on this and more by emailing letters@theneweuropean.co.uk

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37