Italian boxer Primo Carnera’s extraordinary strength and size brought him fame and a sporting career, but not necessarily happiness

As darkness fell over New York on New Year’s Eve 1929, Primo Carrera walked down the gangway of the SS Berengaria, stepped onto the quayside and wondered what the imminent decade held for him. Despite his fellow passengers on the transatlantic crossing including Sergei Rachmaninoff and Sergei Prokofiev, by the time the ship docked it was the Italian boxer who was by far the most eagerly anticipated of the new arrivals.

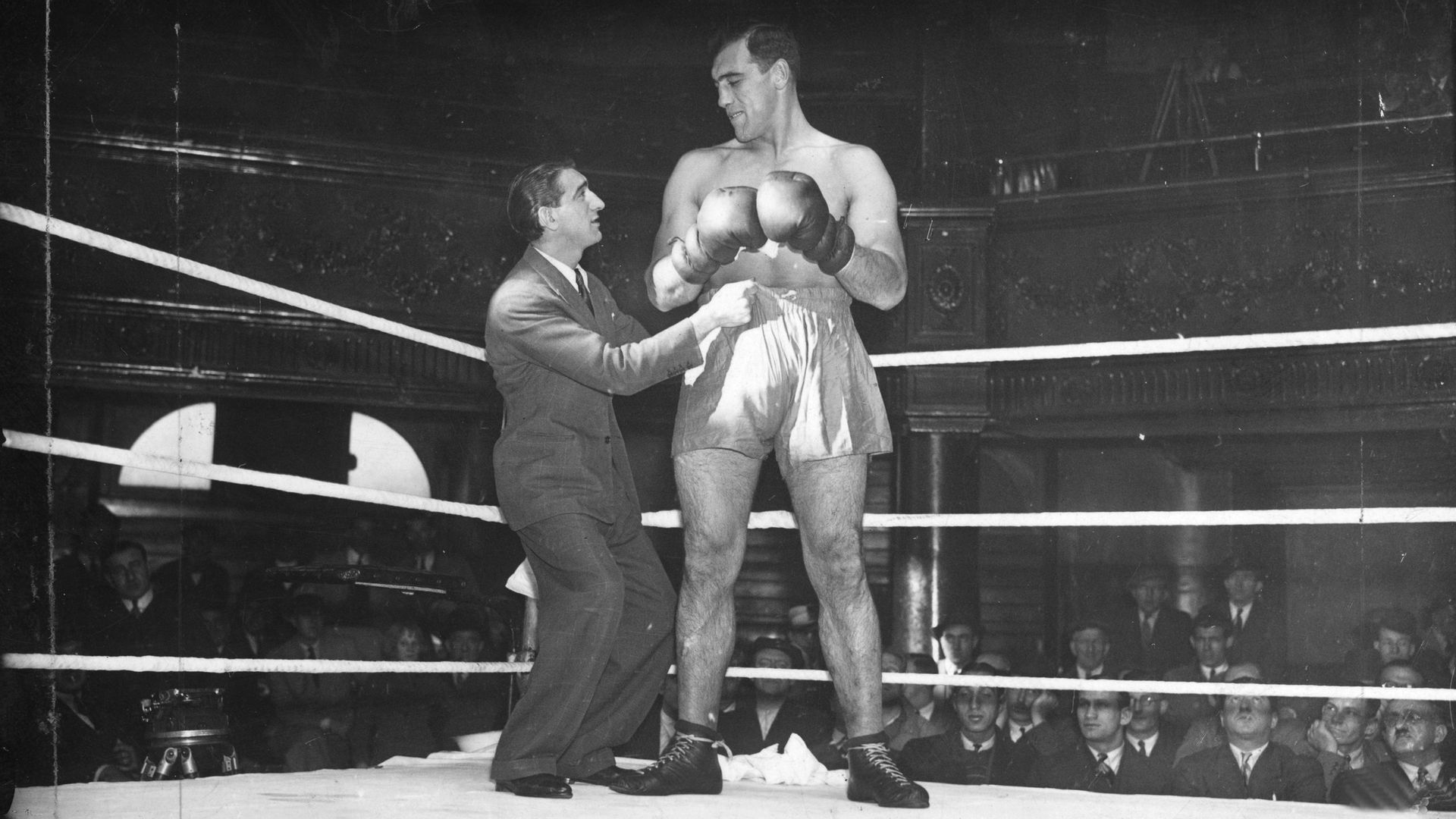

It wasn’t so much Carnera’s prowess in the ring that had caught the attention of the American press. He’d not been fighting long enough for that, and his opponents in Europe hadn’t exactly been stellar names. What tantalised reporters instead were his physical dimensions. The size of his reputation was dictated by, well, his size. It had been that way for as long as he could remember. He’d hoped it might be different here but a glance at the newspapers suggested otherwise.

“They are going to land 280 pounds of imported Italian baloney from the good ship Berengaria this afternoon,” said one New York newspaper. Others speculated whether Carnera would be need to be disembarked by cranes and pulleys. “The human mountain of Fistiana,” they called him, “the mammoth Pisan”, “the longitudinous pug”, even “the big fe-fi-fo-fum man”. Cunard, the papers claimed, had had to construct a specially-made bunk eight feet long to accommodate their towering passenger. It wasn’t just reporters either: the Berengaria’s passenger manifest added the word ‘giant’ to the Italian’s entry under ‘Marks of Identification’.

It felt more like a freak show than the arrival of a notable sportsman. At six feet six inches and almost 20 stone the 23-year-old was certainly a big man but his reception suggested Manhattan was in danger of flipping over the moment he stepped off the ship.

Primo Carnera had hoped boxing might be a route to being noticed for something other than his appearance. It was only a year since his first professional fight and by 1934 he would be heavyweight champion of the world but the circumstances would be far removed from the simple rags-to-riches story he dreamed of.

Within 12 months of arriving in the US Carnera would want to quit the sport altogether. He would be declared bankrupt while holding the world title belt and his victories would be tainted by rumours of mob fixes. It would be many years yet before for Carnera felt in control of his own life, let alone his destiny.

Guileless yet far from stupid, intimidating yet innocent, Primo Carnera spent much of his life searching for where he belonged, a quest that would leave him world famous and desperately lonely. His build made him stand out from the day he was born – his birth weight was a reported 22lb – and by the time he was 12 years old he had outgrown his father’s clothing hand-me-downs. Everywhere he went, for as long as he could remember, people had gawped. Surely in America, a land made for outcasts offering a clean slate of opportunity, he might finally be judged on merits other than his immense size.

It had to be worth a try, anyway. Barely a year earlier Carnera was in Paris, sitting on a park bench utterly disconsolate. He’d left his home village of Sequals in the far north-eastern corner of Italy at 14 and walked to the French capital hoping to make his fortune. A series of dead-end manual labour jobs wasn’t quite what he had in mind so in an attempt to embrace his physical attributes he joined a travelling circus, first as a strongman then as a wrestler.

“It was no life to live,” he said later. “I felt foolish and was very lonely most of the time. I was paid very little, the work was hard and conditions bad.”

After a few years travelling around Europe the circus disbanded and Carnera was back in Paris with no immediate prospects. Having grown up in a rural village he soon discovered how cities teeming with people can be the loneliest places in the world. Sitting on the bench, huge shoulders hunched over, staring at the ground, he presented a sorry sight.

Walking through the park that day in the summer of 1928 was a veteran French boxer named Paul Journée. Noticing Carnera’s remarkable physique he struck up a conversation and before long had persuaded the Italian to try his hand at boxing. Before long Journée had introduced him to his manager Leon See.

“If I had not been broke that day,” said Carnera, “if I had not been so miserable, I do not think I would have gone with Journée to talk to Leon See.”

If Journée detected boxing potential in Carnera, See saw a crowd-puller. He turned Carnera into a professional fighter, arranging a string of no-hoper opponents that helped convince the Italian he had the makings of a world champion when what See really thought he had was a show. Carnera was a spectacle, a gimmick. A good six inches taller and much wider than any other professional heavyweight of the era, he might not win titles but he’d sell a hell of a lot of tickets.

The mob, notably a syndicate headed by notorious New York gangster Owney Madden, also noticed this money-spinning potential and effectively bought Carnera from See and had him brought to America. His shady backer worked him hard – his first fight, a first-round knockout, was just three weeks after he arrived in the US – but Carnera cheerfully got on with dumping opponent after hapless opponent onto the canvas until in 1931 he suffered his first significant defeat, on points to Jack Sharkey. Unsettled by the comprehensive nature of the loss, his relentless schedule and suspecting those controlling his career didn’t necessarily have his best interests at heart, Carnera decided he wanted out of boxing. It was already too late for that.

“They had me by the throat,” he said. “They would not let me quit. I had no friends in the game, nobody I could talk to even, or ask advice. Everyone cared for the money, that’s all. I knew it, and this is a very lonely thing.”

Two years later he was world champion after a return bout with Sharkey, knocking the defending champion out with a right upper cut in the sixth round in an outcome that some still suspect had been pre-arranged. Two successful defences followed, then Carnera came up against the canny Max Baer at Madison Square Garden. He took a brutal pounding that night, knocked down a dozen times but getting up a dozen times before the referee stopped the fight in the 11th round. He might have lost but the way he refused to stay down in the face of some ferocious punching impressed everyone who saw him that night.

“I never liked Carnera before,” said a rival boxer’s manager afterwards. “To me he was nothing but a big, stupid bum. But, by God, I loved and pitied the big, blind ox that night. I never saw so much guts.”

A year later he faced the up-and-coming Joe Louis in front of 62,000 at Yankee Stadium. The fleet-footed Detroit fighter was far too good for the lumbering Carnera who was out-fought, out-thought and knocked out in the sixth round. It was his last high-profile fight, any faint hopes of regaining his world title extinguished.

In the spring of 1936 he took two terrible beatings from Leroy Haynes, the second of which left him in hospital with kidney damage and abandoned by a management that had bled Carnera so dry he was declared bankrupt at the height of his ring success.

“I lay in that hospital bed for five months,” he recalled. “My whole left side was paralyzed. I was in such pain but not one of them came to see me. Nobody came to see me. I had no friend in the whole world.”

After the war Carnera returned to wrestling. Exorcising the memories of his circus days he remained undefeated in his first 120 professional bouts and finally found a sense of fulfilment, living life on his own terms. He also banished the loneliness that had dogged him for as long as he could remember.

“My childhood was very miserable,” he recalled. “At school I was not happy, I was too large to be accepted. Yes, miserable, that’s the word. It was miserable.”

As part of the professional wrestling circuit he was immediately popular with colleagues and fans alike. People no longer gawped, they smiled.

“I never knew a man who liked to be among people so much,” said his wrestling manager Joe Mondt. “I can’t understand it when he tells me he was once afraid of them and lonely. Now, he is never happier than when he is among people.”

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37