For Roland Barthes, the Tour de France was no mere bicycle race. The French literary theorist’s essay Le Tour de France comme épopée, published in his 1957 collection Mythologies, looked at the event not simply as a major highlight of the European sporting calendar but as an “epic” from “a very old ethnic age”, not unlike the Norse sagas or the Arthurian romance of the Middle Ages.

The riders were the heroes of our age, the Tour itself a great quest across an unforgiving landscape where they proved their “courage, loyalty, treachery or stoicism”.

The Tour de France is not a race but a battle fought in blood and sweat against the elements, other seekers of the title and, ultimately, oneself.

European – of course, mainly French – musicians have shared the opinion that the Tour belongs to the realm of myth, and the race and its heroes have been celebrated in song for almost as long as the competition has existed.

Beginning in 1903 as a promotional exercise for the sports paper L’Auto under its bicycling enthusiast editor Henri Desgrange, the Tour de France ran every year until the First World War forced a temporary stop.

But by the 1920s the race was such a prominent feature of French popular culture that it became the subject of popular songs. A nascent celebrity culture was reflected in the song celebrating the Parisian Charles ‘Charlot’ Pélissier, the rider with film star good looks who was establishing himself in the sport at the same time Valentino was in the cinemas, calling him “Les meilleurs des coureurs/ Fameux en tour de piste” (“The best of the riders/ Famous around the tracks”).

In the 1930s ‘official’ tour songs appeared which were often rather martial in their sound and with lyrics that were unalloyed in their praise of the event. The Swiss-born accordionist of Italian descent, Frédo Gardoni, sang several of these songs, as well as others on a Tour theme.

His Le Maillot Jaune of 1936 celebrated the iconic winner’s jersey, won amid “bravos and flowers”, while Edouard ‘Monty’ Montauby’s Ah! Les Voilà!, the official song of that same year, captured the ultimate experience for the spectator – the thrilling moment the riders come into view.

On the eve of war, jazz bandleader Fred Adison, soon to tour with Django Reinhardt, sang the official song, the self-explanatory Les Chevaliers de la route (1939). But the war marked the end of an era, as father of the race Desgrange died in 1940 and the competition didn’t return to the scarred French landscape for seven years.

By the 1960s the Tour was in the middle of its golden age. Popular singer Marcel Amont’s Il a le maillot jaune (1960) reflected that mood, describing the winner riding into Paris, his arms laden with flowers as he crosses the finish line at the Parc des Princes.

The final lines of the song – “Vite à la maison/ Pour voir son triomphe à la télévision” (“Quickly let’s go home/ To see his triumph on television”) – reflected the fact that, while the first live TV broadcast of the race had been as early as 1948, by 1960 it had become a major televisual event.

As the Tour embarked on its second 60 years, the emphasis on uncomplicated, narrative, celebratory songs gave way to a focus on the riders and more complex explorations of the meanings of the Tour.

Anarchic Paris punks Ludwig Von 88’s Louison Bobet for Ever (1987), referencing the great French rider of the 1950s who Barthes described as nothing less than “Promethean”, sung of his “ventre plein d’amphés” (“belly full of speed”), acknowledging the doping that was by then an open secret in the sport.

Taking a similarly sideways look at the Tour was singer-songwriter Fred Poulet with his blues-rocker Walking Indurain (1996), referring to the Spaniard who had just won the Tour five times in a row.

The lyrics made a play on words between “Indurain” and “Sous la pluie” (“In the rain”), while the vocals were delivered like a commentator speaking through an echoey tannoy.

Meanwhile, the Belgian national hero, five-time winner of the Tour and, in the opinion of many, the greatest cyclist of all time Eddy Merckx was the inspiration behind a 1999 techno track by Sttellla.

Formed in Brussels in the late 1970s and named after the much-maligned lager, these proponents of a surreal brand of Belgian humour adorned the track with the sound of spinning gears and ringing bicycle bells.

But more earnest tributes came from elsewhere in the 1990s and beyond. Singer Kent, formerly of French rock band Starshooter, lionised French rider Raymond Poulidor, loved as the underdog who never quite managed to win the Tour despite being in the top 3 eight times, on his Soixante millions de Poulidor (1996). The “60 million” were the whole French population, always “rolling behind” their hero.

Veteran French punks Les Wampas, meanwhile, followed up their 1998 tribute to another French rider never to win the Tour, Laurent ‘Jaja’ Jalabert, with Rimini (2006), their tribute to Marco Pantani, Italian winner of the 1998 Tour whose career, and ultimately his life, was destroyed by doping accusations.

Dutch singer songwriter Dick Annegarn’s dramatic flamenco-flavoured track Agostinho (1990) had similarly honoured a tragic figure of cycling, the Portuguese rider who twice came third in the Tour in the late 1970s before a collision with a dog at the Volta ao Algarve killed him at just 41. The line “À cause d’un chien, on peut tomber” (“Because of a dog, we can fall”) figured the bike race as metaphor for life and its random fates.

But Le Champion Espagnol (2011) by Jean-Louis Murat, dubbed the “poet laureate of contemporary French rock”, is perhaps the most complex of Tour songs. A tribute to Federico Bahamontes, winner of the 1959 Tour and legendary for his success in mountain stages, its atmospheric, sparse guitar sound evokes the arid, cinematic landscapes of the Old West and, indeed, of Mont Ventoux itself, the Tour’s ultimate mountain stage and “the very spirit of the Dry… an accursed terrain, a test site for the hero, something like a higher hell in which the cyclist will define the truth of his salvation”, according to Barthes.

“As in The Odyssey” Barthes went on, “the race here is both a journey of trials and a total exploration of terrestrial limits”, and Ventoux is “an evil god to whom sacrifices must be made”. As Murat pictures Bahamontes, “Le maillot jaune en tête/ Comme un chien affamé/ Ulysse en son royaume/ Fait une offrande aux dieux” (“The yellow jersey in mind/ Like a hungry dog/ Odysseus in his kingdom/ Makes an offering to the gods”), this is where Barthes’ evocation of the mystical power of the Tour and the

exploration of the race in music comes together.

FIVE SONGS NAMED AFTER THE TOUR

André Perchicot, Les Tours de France (1927)

Perchicot was a successful track cyclist but took up singing after sustaining career-ending injuries as a First World War pilot. His song is full of the excitement of the race, everyone turning out to see the riders “beaux sur leur vélo/ Dans leur maillot plein d’élégance” (“handsome on their bike/ In their elegant jerseys”). Its topical reference to Charles Lindbergh’s crossing of the Atlantic in the Spirit of St Louis earlier that year is evocative of the age.

Darcelys, Le Tour de France (1929)

Provençal singer and actor Darcelys began as a cabaret singer and developed a persona on stage and screen as a typical Marseillais character, complete with an exaggerated accent. His 1929 song was the typical fare of the Paris musical halls of the time.

Les Sœurs Etienne, Faire le Tour de France (1950)

Having started their singing careers in wartime Paris, young sisters Louise and Odette recorded a number of close harmony American swing-style songs after the war, including this story of a “un petit gars” (“a little guy”) who realises his dream of becoming “the King of Pedallers”. It was an appropriate celebration of the Tour’s return after the ravages of war.

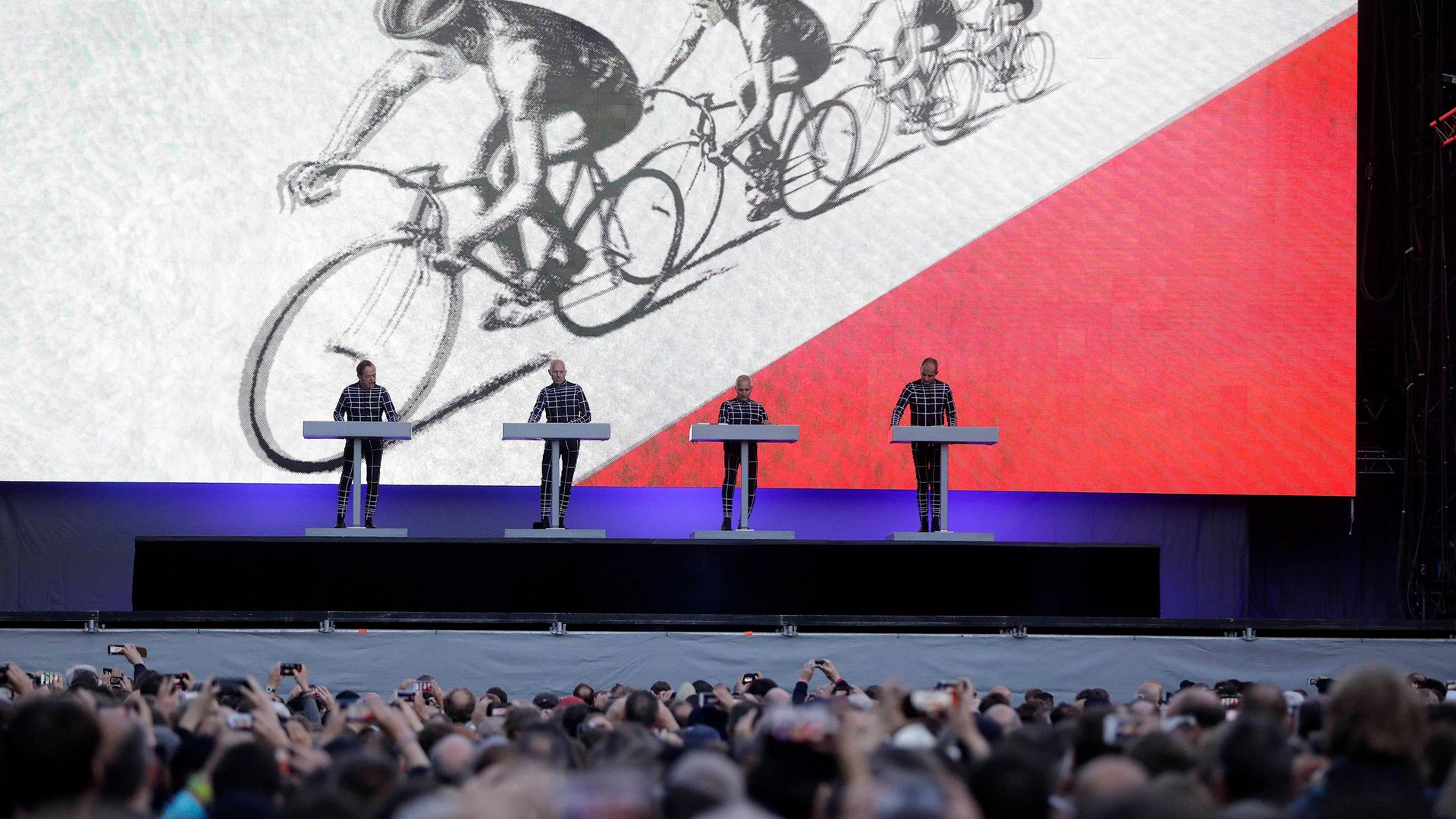

Kraftwerk, Tour de France (1983)

While its 1980s electropop captures the essential dynamism of the race, this track’s lyrics are typically cold and unemotional, simply enumerating the stages of the race (“Les Alpes et les Pyrénées/ Dernière étape Champs-Elysées“), until the concluding line suggests the deeper meanings of the event: “Camarades et amitié“, (“Comrades and friendship”). The album Tour de France Soundtracks, released on the 2003 centenary of the race, contained a new version of the 1983 hit.

Litku Klemetti, Tour de France (2021)

The Finnish solo artist makes a return to the bright synths of Kraftwerk’s own effort in this attitude-laden, danceable track which uses bicycle riding as a byword for freedom.

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37