Such is Liverpool’s immense musical heritage that the city is not overshadowed by its most famous sons

Liverpool makes its own mythology. In February 1967, the Beatles released the double A-side Penny Lane/ Strawberry Fields Forever, not only creating a new paradigm for Britishness in pop on one side and all but single-handedly creating psychedelia on the other, but bathing Liverpool in a magical light which hasn’t faded since.

For war babies like themselves, these songs made the Beatles not only definitive of a new era of liberation and mind-expansion, but of the transcendent magic of a post-war childhood.

While these were songs that could only have come out of the working class north of austerity and the hopeful 1950s – they were inspired by the particular experiences of playing in the wooded grounds of the Strawberry Field Salvation Army children’s home and waiting for the bus at the nondescript suburban junction on Penny Lane – a whole generation could relate to their enchantment and nostalgia.

But the Beatles only got to the point of being able to create such magical worlds because of the very practical benefits to music-making their city offered, and Liverpool’s musical fecundity over the past 60 years has been due to a strong self-starting impulse.

In that time, the city’s musical infrastructure – a network of ad hoc clubs, self-appointed Svengalis and little bands putting themselves together on meagre resources and, initially at least, limited musical skill – has been a springboard to making a sometimes era-defining impact on the wider world.

Merseyside in the 1960s was a musical primordial soup. As the jazz explosion of the 1950s segued into skiffle, Liverpool’s clubs were alive with these sounds, and it provided the prelude to what was to come. The teenage John Lennon formed the skiffle band The Quarrymen, complete with washboard and homemade tea chest bass, in 1956, but popular music was moving at breakneck speed.

Already that year the UK charts had hosted the debut hits of Little Richard, Elvis Presley and Gene Vincent, and by the time of the famous meeting of Lennon and McCartney at the St Peter’s, Woolton, church fete in July 1957 the paradigm had irrevocably shifted.

By 1961, the Liverpool scene had flourished to such an extent that there was plenty of material for the fortnightly Mersey Beat music paper to launch. The events of that year illustrated the musical diversity of Liverpool already on show: a mistake in Mersey Beat inadvertently gave local singer Cilla White her stage name; there were Top 5 hits for local ex-docker Billy Fury; Gerry and the Pacemakers got their management deal; and Rory Storm and the Hurricanes, featuring drummer Richard Starkey (aka Ringo Starr) switched from skiffle to rock ‘n’ roll mid-set at The Cavern on Mathew Street, to the displeasure of the assembled traditionalists.

Just as Mersey Beat was put together on scant resources in an attic above an off licence, Liverpool’s march to becoming the centre of the pop universe took place through a hodgepodge of unlikely venues. The short-lived Casbah Coffee Club – opened in the basement of a Victorian house in West Derby owned by Beatles drummer Pete Best’s mum, Mona – was an early training ground for The Quarrymen, providing an alternative to the city’s established jazz clubs where, as Rory Storm had discovered, rock ‘n’ roll was at first spurned.

Mona Best also organised performances at St John’s Hall in nearby Tuebrook, and there were early gigs at assorted Conservative clubs, village halls, dance halls and even the social club attached to the abattoir in Old Swan. The famous Cavern residency only came after the band had cut their teeth at this patchwork of venues and the club had finally shed its ‘jazz only’ policy.

But Liverpool also offered the infrastructure for recording and management and, therefore, breaking out into the national, and even international, consciousness.

Sometime between late 1957 and mid-1958 The Quarrymen recorded two songs, including a cover of That’ll Be the Day, at Percy Phillips’ Phillips Sound Recording Services located at his terraced house in the Kensington area of Liverpool. Then Brian Epstein came along. Proprietor of the North End Music Stores (NEMS) of Great Charlotte Street and Whitechapel, which the Beatles all patronised, he was a man with a vision that far exceeded such limited horizons.

With a year at RADA under his belt, Epstein grasped the importance of the visual in pop performance and, having signed the Beatles to a management contract in 1962, set about giving them their signature look. Their EMI record deal followed within a few months and they were at UK No.1 in less than a year.

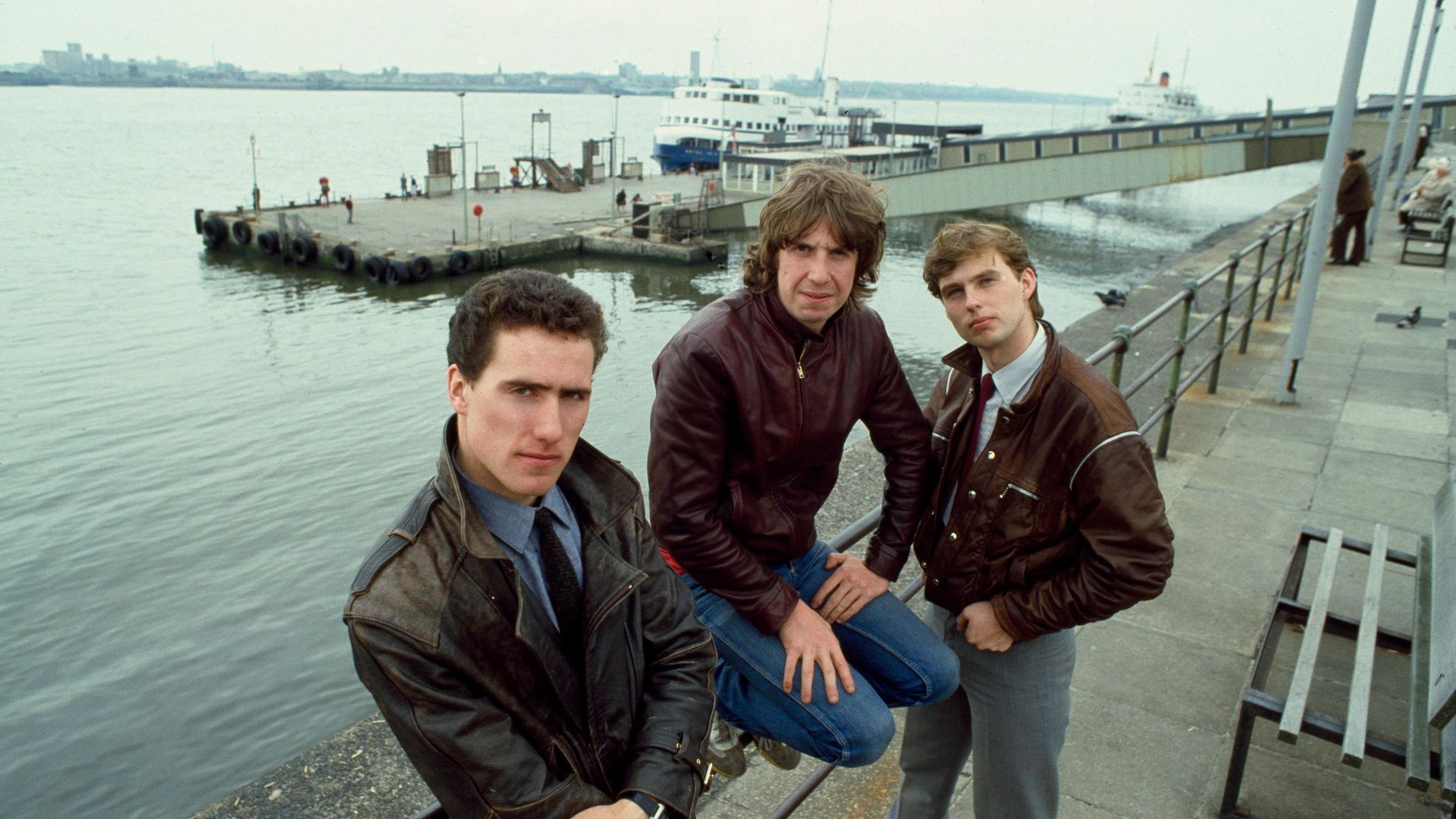

Just as the Beatles had NEMS and The Cavern, punk, post-punk and beyond had Probe Records and Eric’s Club, and the Liverpool scene of the late 1970s produced some of the most boundary-pushing music of the era. Opened by Geoff Davies on Clarence Street in 1971, Probe was originally a haven for the assorted genres of hippiedom, and a second shop followed in 1974 in the suitably ‘far out’ Silly Billy’s fashion boutique in Whitechapel. But it was the Button Street store, opened in 1976 in an imposing building with a steep stepped entrance just a stone’s throw from Mathew Street, which became a punk, new wave and reggae mecca.

One Pete Burns was a Probe Records employee, his horror-androgyne look and close policing of customers’ taste being legendary, and he was also a regular at Eric’s, the club opened on Mathew Street by Roger Eagle the year before punk exploded. While it was a rather more professional outfit than Mona Best’s basement, Eric’s had the same pioneering spirit, and the club became the heart and soul of alternative music in Liverpool.

Burns made an early appearance at Eric’s in November 1977 as vocalist with the Mystery Girls, which also included local man Pete Wylie and Welsh teacher training student Julian Cope. Their first gig, supporting Sham 69, was also their last, but the one-off experiment demonstrated how Eric’s provided a forum for the new and for the launching of careers.

Burns would go on to form the less than prolific Nightmares in Wax – although their Black Leather (“I am what I am/ And I like what I like/ And I like it on the back of a motorbike”) is deserving of classic status – before entering pop stardom when You Spin Me Round (Like a Record) got to No. 1 in 1985. Wylie’s Wah! had had a hit with The Story of the Blues in 1982, while Cope’s The Teardrop Explodes’ frenzied Reward had just missed the Top 5 in 1981.

Eric’s gave birth to an incredible array of successful acts. Like The Teardrop Explodes and Wah!, both OMD and Echo and the Bunnymen played their maiden gigs there, while the typically short-lived Big in Japan’s last appearance was at the club in the summer of 1978 – members included Holly Johnson (Frankie Goes To Hollywood), Bill Drummond (The KLF, with the Wirral’s Jimmy Cauty, later of The Orb), Ian Broudie (The Lightning Seeds), and Peter Clarke (The Slits and Siouxsie and the Banshees).

But before Eric’s, Probe’s golden years on Button Street, and the launch of shop’s record label, which hosted such avant-garde experiments as Half Man Half Biscuit, there had been an earlier catalyst for musical mould-breaking. The Liverpool Art College’s 1973 Christmas dance anticipated the DIY ethos of punk by calling for anyone who fancied having a go to perform, and performance art band Deaf School was formed in response. With Roxy Music’s art rock sensibility but punk’s gung-ho approach to musicianship, they heralded a new era in Liverpool music 10 years after the Beatles had said farewell to the Cavern.

Like so many Liverpool bands before and since, Deaf School had needed nothing more than their own initiative to make something happen. As the late Pete Burns put it to the Guardian in 2003: “No f**king fairy godmother came down my chimney and said, ‘You’ll go the ball’. I got on the f**king guest list myself and made my own dress to go in.”

MERSEYSIDE’S MEGAHITS

Lita Roza’s 1953 cover of (How Much Is) That Doggie in the Window?, released not long after the pop charts began in the NME, was the first of the more than 50 British No. 1 hits by artists from Liverpool. 2012 Christmas No. 1, The Justice Collective’s cover of He Ain’t Heavy, He’s My Brother, featured Liverpool’s Holly Johnson, Paul McCartney, Gerry Marsden (Gerry and the Pacemakers), John Power (The La’s and Cast), Dave McCabe (The Zutons), Peter Hooton (The Farm), Melanie C and Rebecca Ferguson, raising funds for the continued fight for justice after the release of the Hillsborough Independent Panel report.

What do you think? Have your say on this and more by emailing letters@theneweuropean.co.uk

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37