An anti-lockdown politician has young crowds chanting her name in the streets and the ruling Socialists on the run

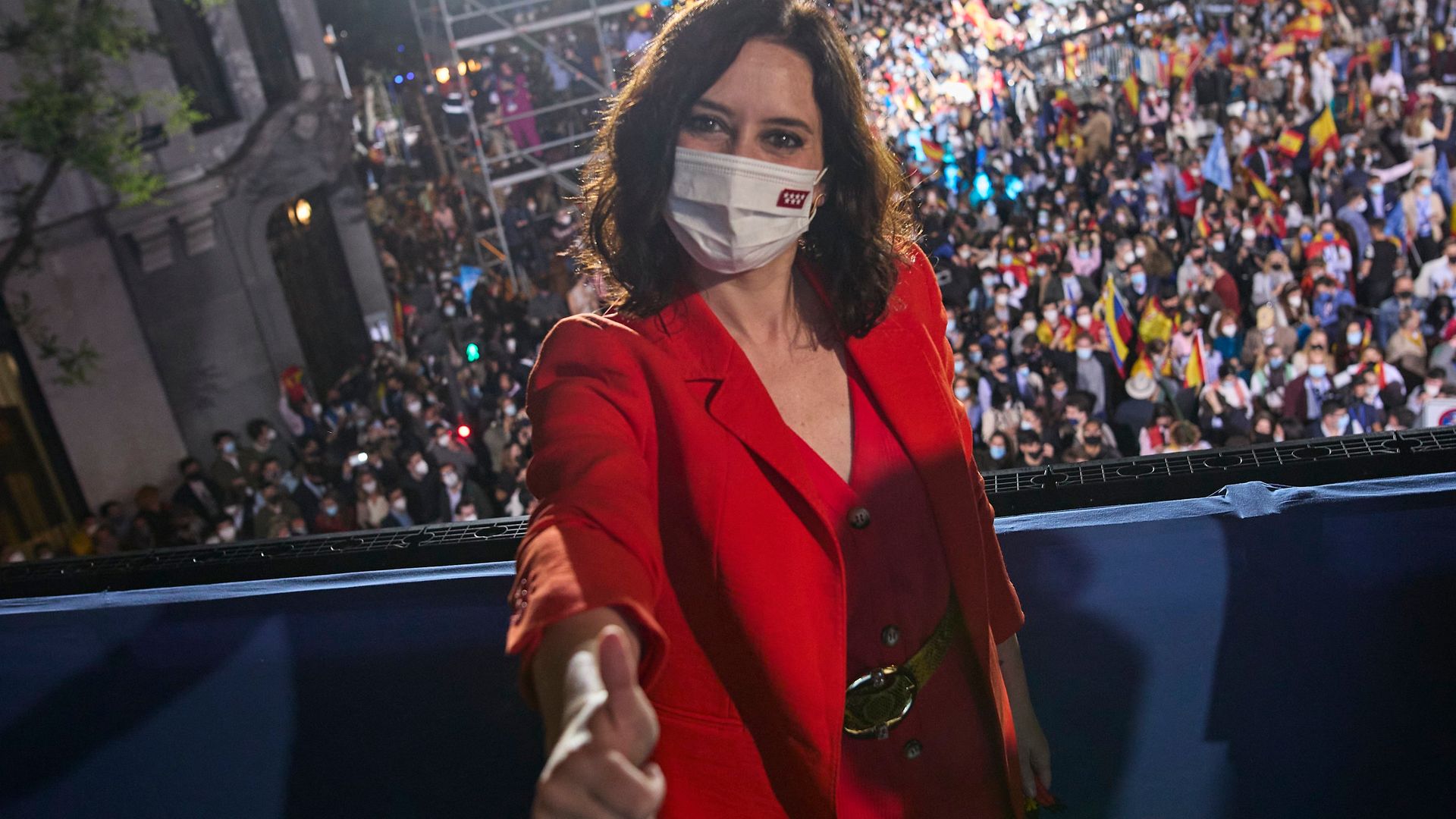

As midnight struck on Saturday hundreds of young people headed for the Puerta de Sol in downtown Madrid to celebrate the lifting of Spain’s state of emergency. They danced congas and partied like it was New Year’s Eve, singing and chanting “freedom” and “Ayuso” outside the regional government headquarters.

“Ayuso” is Isabel Diaz Ayuso, the pugnacious right-wing president of the region of Madrid and “freedom” (from pandemic restrictions) was the slogan she used in her successful campaign for re-election last week. She more than doubled her seats in the local parliament, obliterating in the process her former coalition partners Ciudadanos and handing the prime minister Pedro Sanchez’s Socialists their worst-ever defeat in the region. She will be able to govern with an abstention from the far-right Vox party.

For students to be chanting her name is a mark of how far this until-recently obscure politician has travelled in the 18 months since she was handpicked by the Popular Party leader Pablo Casado to run for president of the region. From managing the Twitter account of a previous president’s dog, Pecas, she’s now being dubbed “the Spanish Thatcher” and is talked about as a possible successor to Casado.

Her victory has given fresh impetus to the conservative PP, which has dominated Spanish politics since the restoration of democracy four decades ago but has been mired in corruption allegations and an identity crisis since power was audaciously snatched from them by Sanchez in a no-confidence vote in 2018.

Under the tutelage of Miguel Angel Rodriguez, a former adviser to ex-PM Jose Maria Aznar with the same guile as Dominic Cummings, Ayuso’s strategy has been one of permanent confrontation, resisting the Covid-19 measures imposed by the national government. In the process she has gained cult status among bar and restaurant owners, who in defiance of scientific advice have been allowed to remain open for the past year (albeit with some limitations).

With no small amount of luck thanks to the capricious nature of the virus, her approach has paid off, says Alejandro Quiroga, a professor in modern history at the Universidad Complutense de Madrid. Covid infections, while double the national average, haven’t spiralled out of control to the extent that hospitals have been inundated. Other regions such as the Basque Country, which imposed much stricter measures, have fared worse. Ayuso and madrileños appear to have accepted the trade-off of more deaths in exchange for keeping small businesses alive.

Casado has until now struggled to forge an identity for his party in a landscape where a number of new parties have emerged to chip away at the margins of its support both in the centre and on the right. Ayuso successfully attracted votes from frustrated Ciudadanos voters while holding off a challenge from Vox by matching them in confrontation and provocation.

Her populist approach during the pandemic, which mixed victimhood – she claimed the national government was punishing Madrid for voting right – with playing up ideas of a madrileño identity, have made the PP – at least in Madrid – into a party that’s closer to Boris Johnson’s Tories than Angela Merkel’s CDU and will give Casado food for thought.

Whether Ayuso’s pugilistic style would wash in the rest of Spain is less clear. But her victory in Madrid certainly has repercussions for national politics. Ciudadanos, which as recently as three years ago topped national polls, is now staring at the abyss after failing to win a single seat in the Madrid parliament. The party set in motion the chain of events after it proposed a vote of no-confidence against the PP in the region of Murcia, where the two parties shared power. That prompted Ayuso to call an early election in Madrid using the pretext that she believed Ciudadanos would file a similar motion against her.

The result is that from holding the vice-presidency of the region and 26 seats in parliament, Ciudadanos has lost power both in Madrid and Murcia.

The election was also costly for Podemos, the anti-austerity party that burst on the scene a decade ago in the wake of the financial crisis. Its leader and founder, the pony-tailed Pablo Iglesias, puzzled many observers by stepping down from his position as deputy prime minister in a coalition government with the Socialists to run against Ayuso. He announced his intention to retire from politics after failing to make headway and losing ground to another left-wing party, Mas Madrid.

The demise of Ciudadanos leaves a void in the centre that will be absorbed by the two traditional parties, the PP and the Socialists, marking a small step back toward the two-party system that dominated Spanish politics before the financial crisis. But the PP will still face pressure from Vox on its right while there’s still space for some form of left-wing party to emerge to challenge the Socialists on their left flank, says Antonio Barroso managing director at political risk firm Teneo.

It will be a worry for Sanchez how poorly the Socialists fared in an urban setting. Still, there’s little appetite for now to topple his fragile government. But what is certain is that Ayuso has reinvigorated the right in Spain, and that should Sanchez stumble the PP may have found a formula to challenge him.

What do you think? Have your say on this and more by emailing letters@theneweuropean.co.uk

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37