Every November, Germany and the world remember the Day of Fate. November 9 is pockmarked with terrible events, including Kristallnacht, the rampage against Jews that culminated in the Holocaust. Now it is synonymous with the fall of the Berlin Wall.

I was recounting to a friend and former boss my great fortune at witnessing that moment in 1989. I had arrived in communist East Berlin at the start of the year as the Telegraph’s correspondent. “My memory extends a little further back than yours,” came the dry reply of Annette von Broecker. She had seen the wall go up in 1961 – 60 years ago this summer – something far fewer people can claim to have done.

The story of this veteran journalist provides a window on post-war Germany. One of her first memories was of a Russian called Anatoly. A war baby, she was four when the Soviets descended on devastated Berlin. Unlike many of the stories of rape and pillage, she remembers her mother being politely asked for a glass of water before the soldiers went on their way.

Her apartment is on the Western fringe of the city, the ‘old money’ part that extends between Charlottenburg and the villas that surround Grunewald, the hunting grounds of past kings.

The Russians moved east, leaving the area to the Brits, who signalled their arrival by flying Lancaster bombers low overhead, looking for final targets of resistance to bomb. The locals were spared because Hitler’s Olympic Stadium nearby had been earmarked as the British military HQ. But they did billet in the houses, forcing many locals out.

Von Broecker’s mother had the guile to transform their ground floor apartment overnight into a very un-German mess. “It was an impressive slum,” she recalls.

The occupiers took one look and left.

Von Broecker grew up with the Brits, with young Billy, the son of an officer’s family in the house next door. Her father, a sound engineer, found himself a job working for the occupying radio station, RIAS, or Radio in the American Sector. There began an emotional bond with Britain, one that now, as with so many Germans, is suffused with Brexit bewilderment and sadness.

This was the Berlin of cutting down trees for fuel, of exchanging heirlooms for cigarettes. During the 1948-49 blockade, people did what they could to bring in food. She recalls the day one of her father’s work colleagues went to the East, which still had basic provisions. “This lady came into our apartment, went straight to the bathroom and emerged with some pork cutlets in her hand. It turns out that she smuggled them over the border inside her corset.”

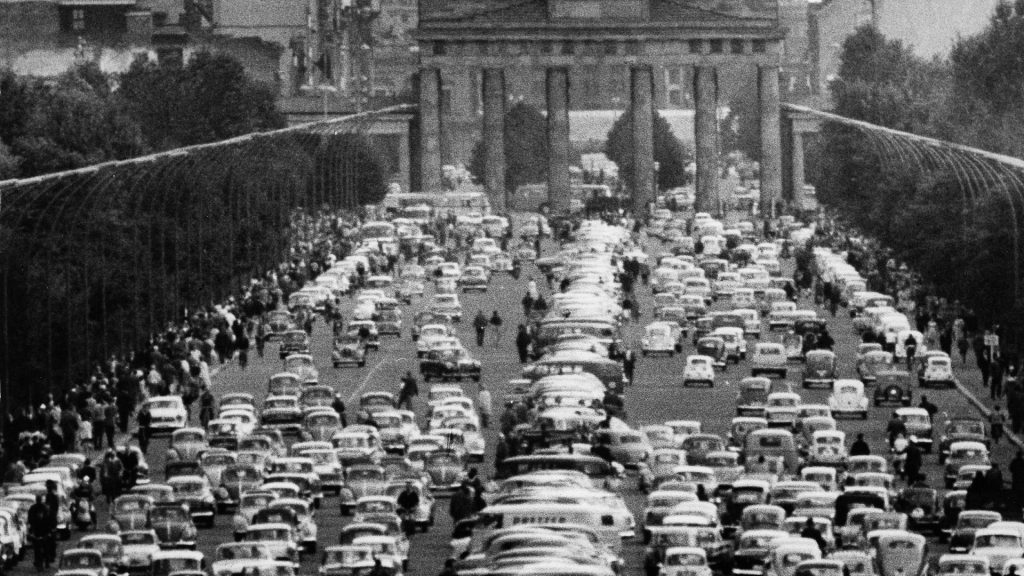

During the 1950s, West Berliners were subsidised to stay and not to move to other parts of West Germany. Meanwhile, thousands of East Berliners were crossing over every day as the communists tightened their grip and as living standards plunged. By the end of the decade. tensions were peaking.

In 1959, her mother spotted an advertisement in a local paper. It was for an editorial assistant at the Reuters news agency. Neither had a clue what it was, but it sounded interesting. The position required good English and Abitur (the equivalent of ‘A’ Level) qualification. The 19-year-old daughter had neither but applied anyway. “I wanted to be an artist, but I thought that this would be an adventure,” von Broecker tells me. “I thought they sold news and didn’t understand there was no cash register.”

She learnt to read telex code and acquired the basics. Within two years she found herself witness to one of the great moments of history.

Berlin Eastern Sector August 13 Reuters – the East West Berlin border was closed early today.

This ‘snap’ report was filed by von Broecker’s colleague, Adam Kellett-Long, the only Western journalist accredited to East Germany at the time. He had been tipped off that something was afoot. A male voice had phoned him with a piece of advice: “Don’t go to bed tonight”.

Two days earlier, the East German parliament, the Volkskammer, had passed a resolution authorising the government to “take all necessary steps” to prevent the further flight of East Berliners to the West. But as Kellett-Long recalls: “Of all the options, none of us thought they would build a wall.”

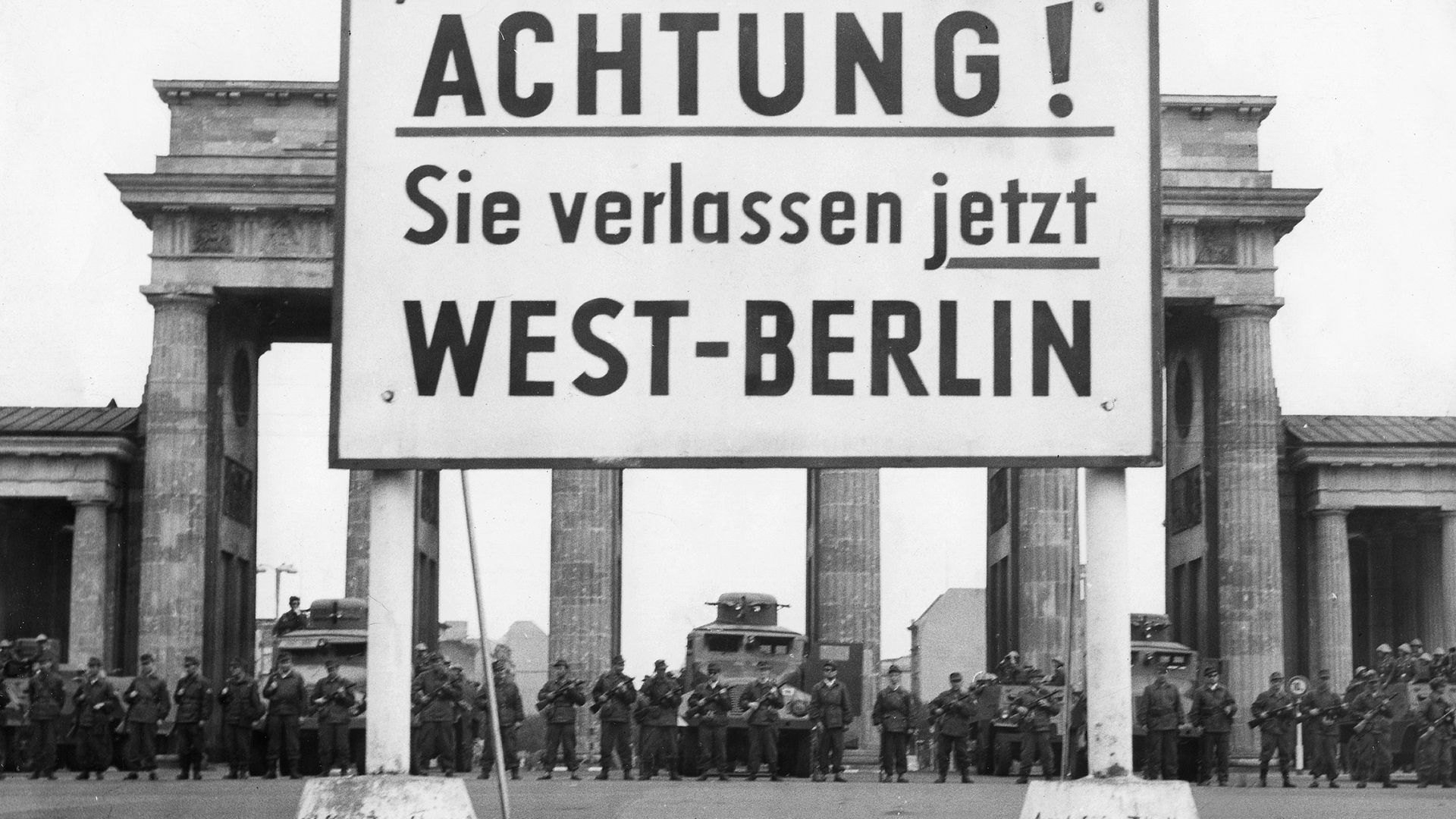

At shortly after midnight, the East German news agency, ADN, cranked into action with a report expressing the Warsaw Pact’s approval of emergency measures. Kellett-Long jumped in his car and rushed to the Brandenburg Gate. He was stopped by a policeman waving a red torch, telling him that he could go no further. “The border is closed,” he said. That was enough. He rushed home, past a phalanx of military vehicles heading in the opposite direction, to file his urgent report.

Across the now-divided city, at about 1.30am, von Broecker was telephoned at her mum’s flat by the news desk in London with Kellett-Long’s report. Earlier in the day she had been with him in the East Berlin office. She had taken a taxi back to the West, but was stopped by soldiers and told to go through the Brandenburg Gate by foot. “I still get the jitters when I walk through, thinking there might be a Kalashnikov behind me,” she says.

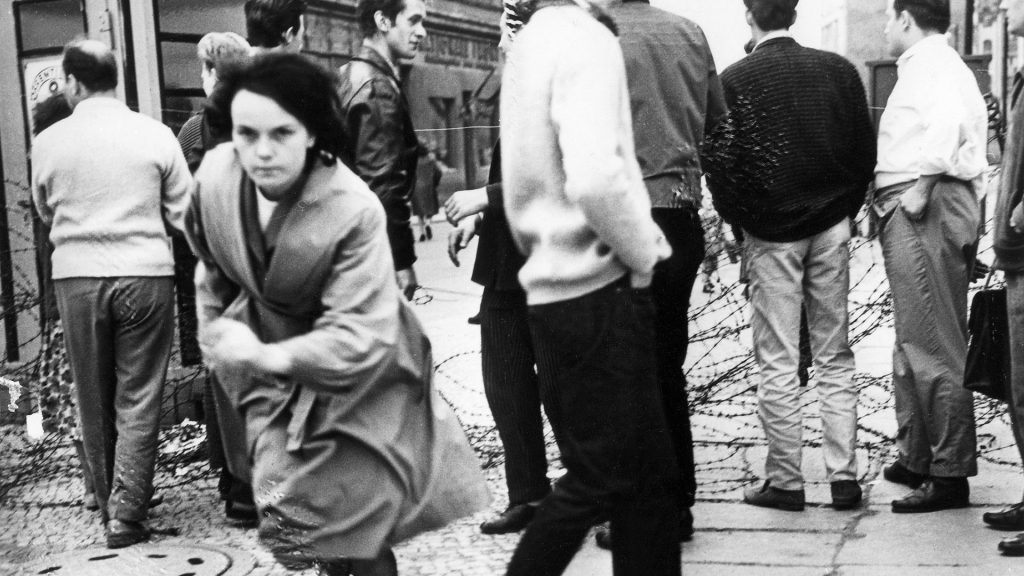

Back at the gate, on the western side, in the middle of the night, von Broecker and watched as soldiers and elite “factory military forces” erected barbed wire and the first concrete slabs. One West Berliner reached across to a soldier, offering him a cigarette in the hope of persuading him to down tools.

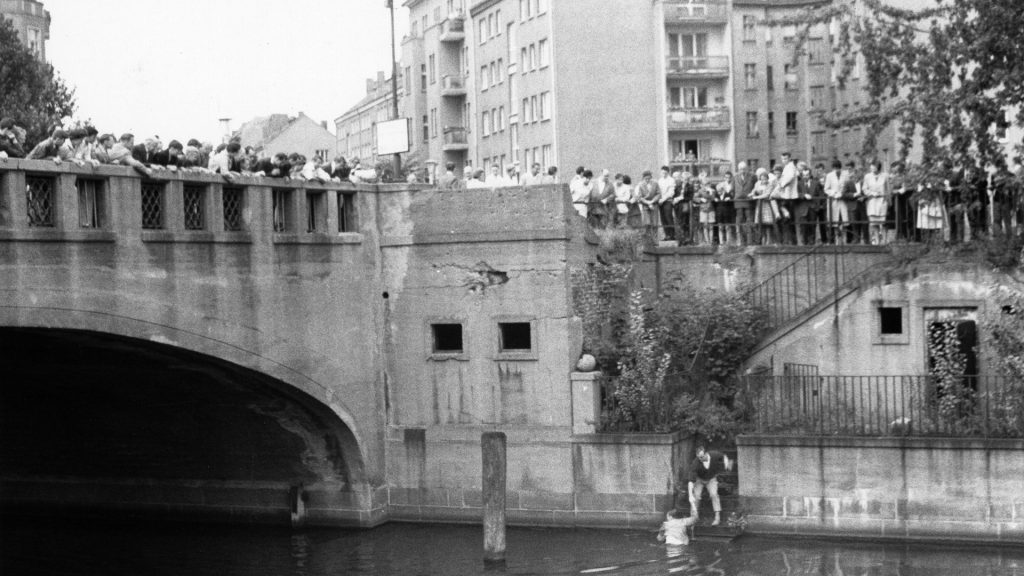

Early the next morning she was at Tempelhof airport to watch the mayor, Willy Brandt, fly back to the city (he had been elsewhere in Germany campaigning) to warn of the “danger of civil war”. She went to other parts of the new frontier to report on East Germans frantically trying to escape, sliding down bedsheets from the side of buildings.

Her biggest moment was to come six months later. The Americans and Russians agreed to swap two spies – Gary Powers, a CIA reconnaissance pilot shot down in the Urals, and Rudolf Abel, a Soviet spy convicted in New York. They were brought to Berlin where, early one February morning, the world’s media gathered at the Brandenburg Gate.

Von Broecker told her boss she had a hunch it wouldn’t happen there. She asked if she could take a taxi to the southwest of the city, to the Glienicker Bridge that separated it from Potsdam in the GDR. She was the office junior, so why not indulge her flight of fancy?

By the time she had arrived, the Americans had already whisked their man away. The German police were also moving off. The glamorous trainee found an officer and entreated him to tell all. They went into the woods next to the bridge, so as not to be observed, and he gave her the whole story. She then rushed to a nearby pay phone and dictated what she had been told.

“When we got back to the office, some of the journalists were a little sour with me,” she recounts. They did not appreciate being pipped to the story by “a girl”.

Still, they took her to a cake shop to celebrate.

Von Broecker went on to become one of Reuters’ finest, but because of the rule of no by-lines she never became famous, as she might have done. She witnessed the Prague Spring, the death of Tito, the aftermath of the Iranian revolution… and many of the great moments of Cold War history.

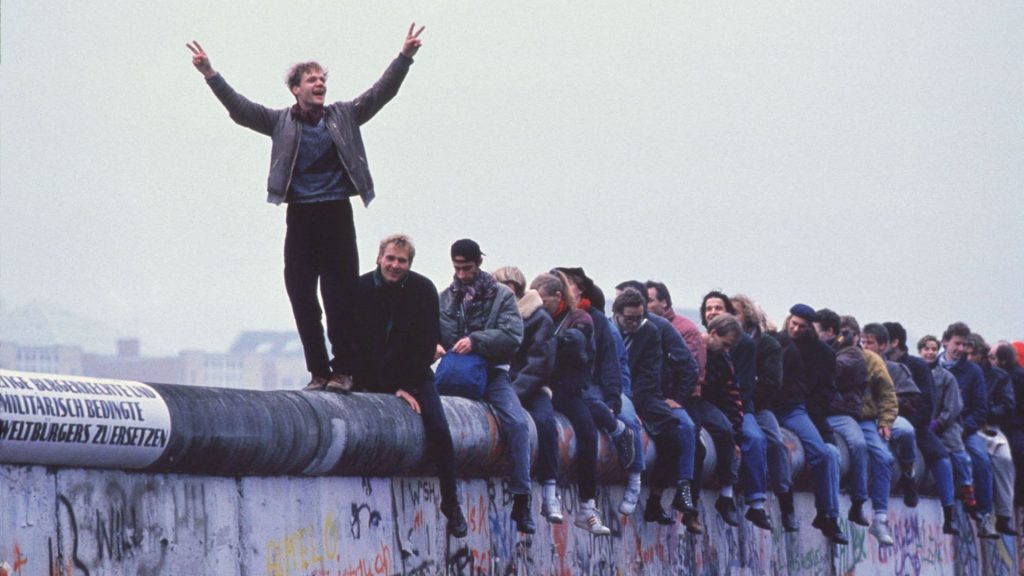

That era ended equally dramatically as it had begun, those scenes of East Berliners rushing to the checkpoints within hours of the accidental announcement of the border opening. I had the privilege of following in von Broecker’s footsteps and reporting on the breaching of the fortification, seeing Trabants splutter over the border and people celebrating on the wall with champagne, or chiselling a piece of concrete as a memento.

The wall has now been down for longer than it existed. For many who have moved to Berlin – Germans and foreigners alike – it is nothing more than a piece of exotica. Unlike von Broecker, I don’t feel a chill in my spine whenever I walk through the Brandenburg Gate, but even now I can trace the wall for miles around.

If you were there, it never really leaves you.

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37