Remembering the moment when the world’s most famous sportsman was bundled out of his hotel by rebel gunmen

Sport and politics have always mixed, but they have never collided quite so spectacularly as they did in the lobby of Havana’s Hotel Lincoln on February 23, 1958. That day, as five-time Formula 1 champion and possibly the most famous sportsman on the planet Juan-Manuel Fangio stepped out of the lift he was confronted by a nervous-looking man who pulled a pistol from the inside pocket of his jacket and instructed the driver to follow him.

Fangio was bundled into one of three getaway cars waiting outside, which sped off down the streets of the Cuban capital, sparking one of the most curious chapters in motorsport history.

In truth, this was a story not about the sport but Cuba’s troubled, volatile politics. The Argentinian, who was the reigning world champion, was on the island to take part in the second Cuban Grand Prix. And although it wasn’t a Formula 1 championship race all the big names of the day were there – Britain’s Stirling Moss, Le Mans 24-Hour race winner Carroll Shelby, and future world champion Phil Hill among them – attracted by big money on offer from the Cuban government.

This was where the politics came in. Cuban president Fulgencio Batista y Zaldívar had ruled for 25 years. Corrupt, authoritarian and latterly a puppet of the US government, he had turned Cuba into a playground for rich, partying Americans and their business interests, alongside casinos, nightclubs and brothels run by the American mafia.

The capital Havana had already pretty much morphed into a Cuban Las Vegas and Batista was banking on a high-stakes motor race bringing him even greater kudos on the world stage and, crucially, more cash for the coffers. Fangio had already won the first race along Havana’s famed waterfront, the Malecón, the year before and was back with the intention of retaining his title.

But dissent against the Batista regime had long been fomenting. Leftist revolutionary rebels led by Fidel Castro had attempted to overthrow the military dictator in 1953 but were defeated. Exiled to Mexico, Castro had returned with his brother Raul in 1956 alongside charismatic Argentinian revolutionary Ernesto ‘Che’ Guevara, determined to liberate the poor of Cuba from the mendacity of Batista’s increasingly immoral regime.

They had holed up in the Sierra Maestra mountains where the insurgency had slowly gained the support of Cubans tired of poverty and unemployment, and resentful of the intimidation, imprisonment and torture of Batista’s political opponents.

Yet Castro had figured that there was more than one way to skin the presidential cat. Violent insurrection had its drawbacks, especially in the capitals of nations Cuba would need as allies if the revolution was successful. But embarrassing the Batista government just as it was trying to shine on the world stage by hosting a major sporting event might generate headlines without – hopefully – a bullet being fired.

Naturally Batista billeted the world’s greatest drivers in luxury, but seemed notably gung-ho about the security of those he had invited, meaning the kidnapper was able to approach Fangio, who was with friends, in the hotel lobby.

“In the name of the 26th July revolutionary movement you must come with me,” he said to the driver. Fangio knew who he represented. Named after the date of Castro’s first attempt to overthrow Batista in 1953, the organisation was well known in Argentina because of the link with Guevara. He clearly wasn’t in a position to argue. “Stay still or I shoot,” the assailant’s accomplice shouted at Fangio’s party, as Batista’s star attraction was bundled away.

The kidnappers had also come looking for Moss, Fangio’s team-mate, but the latter told them that searching for him would likely mean the police would be at the hotel before they left. He also told them Moss was on his honeymoon. It wasn’t true but it gave the rebels second thoughts. Moss was eternally grateful – “A genuinely decent act,” admitted the Briton – and spent the night under armed guard.

Meanwhile, the story was wired around the world, shaming the Batista government which attempted to spin the story, insisting Castro and his henchmen were little more than bandits and extortionists while proclaiming the race would go ahead as planned. But Castro was cannier than that.

He knew the abduction would not have the support of the general public if any harm came to the driver. Fangio was the son of a peasant himself and stood alongside his revered footballing compatriot Alfredo Di Stéfano as twin emblems of how sporting talent could earn their nation and their continent worldwide respect.

Castro was well aware that popular revolution would not be roused across Central and South America if it involved killing one of its most famous sporting sons. Everybody loved Fangio. Making him a martyr for Batista was always going to be an impossible sell. Castro wasn’t going to harm his hostage however much Batista pretended otherwise.

Police chiefs believed Fangio had been driven into the mountains but he was actually held in a nearby apartment block where he was fed a steak dinner, given paper to write a letter explaining how well he was being treated and a radio to listen to the race commentary the following day.

The last thing the kidnappers wanted was for their captive to be shot in a firefight with any would-be rescuers so, after they released Fangio’s letter, they arranged for him to be dropped off close to the Argentinian ambassador’s residence in Havana on the evening after the race.

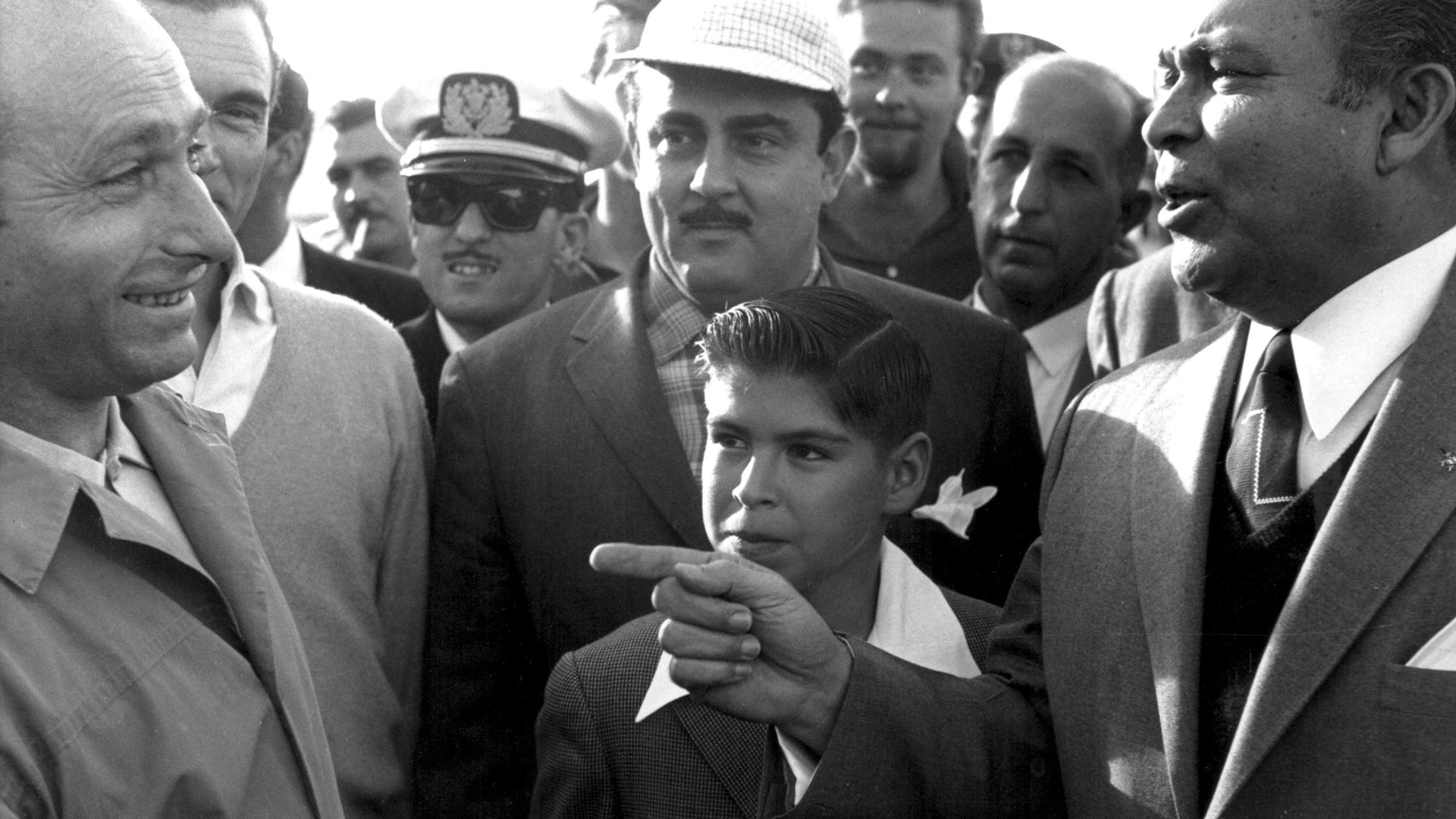

With the police still searching, further discomfort was heaped on the government when Fangio popped up at a press conference to say he had never felt threatened, slept very well and sympathised with his captors.

“If what the rebels did was in a good cause then I, as an Argentinian, accept it,” he told the world’s press, as he was offered a personal apology by one of Castro’s representatives, Faustino Perez, and told he would always be a welcome guest in Cuba. “We got on well, they were just making a political point. I simply saw young people with what they felt was a just cause,” Fangio added.

While he had been away farce had turned to tragedy for the Cuban government. Their attempts to show the world that it was business as usual in Havana with the race going ahead as planned backfired when after only six laps tragedy disaster struck. Roberto Mieres’ Porsche broke an oil line, spraying the track. Local driver Armando Garcia Cifuentes lost control on the slick, careening over the barriers into the packed crowd, demolishing a bridge and killing seven people.

The organisers at first attempted to blame Castro-supporting saboteurs for soaking the track in oil, but the drivers made clear what had happened after the race was abandoned and Moss was handed the victory for being in the lead at the cessation. “It really didn’t matter by then,” he said, “with everything that happened that weekend.”

Castro’s plan had worked a treat, Batista’s government was humiliated. By the time of the third – and last – Cuban Grand Prix in 1960, the revolution had been successful, Castro was prime minister and Batista was in exile in Madeira. Fangio had retired by then but Moss would go on to win once more, this time in less painful circumstances, before the Cuban authorities deemed motorsport too bourgeois and cancelled the race.

Juan-Manuel Fangio died in 1995 but on his 80th birthday four years earlier among the cards he received was one from Cuba signed “Your friends, the kidnappers”. “I never identified them,” said Fangio. “They didn’t forget.”

Whether it was sent by those who actually carried out the deed is uncertain, but it showed that 33 years on there were still people on the island who appreciated a guest who arrived as a sporting idol but departed as a political ambassador for their cause.

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37